Viewers of Apple TV’s new science fiction series, Plur1bus, have been quick to point out eerie similarities with modern concerns about artificial intelligence (AI) – even if that’s not what it’s maker intended.

Writer and producer Vince Gilligan – who also created Breaking Bad and Better Call Saul – told Polygon he wasn’t thinking of AI when he had the idea for the series:

Because this was about eight or ten years ago. Of course, the phrase ‘artificial intelligence’ certainly predated ChatGPT, but it wasn’t in the news like it is now. […] I’m not saying you’re wrong […] A lot of people are making that connection. I don’t want to tell people what this show is about.

In Plur1bus, an alien-made “virus” comes to Earth and begins to infect everyone. While the infected are physically untouched, they are stripped of emotion and individual consciousness. They become part of a single collective “hive mind”.

This plot might sound familiar if you’ve seen Don Siegel’s 1956 film Invasion of the Body Snatchers, remade by Philip Kaufman in 1978 and adapted several times since. It returns in Plur1bus, but with some key differences.

In episode one, we meet Carol Sturka (Rhea Seehorn), a cynical, alcoholic romance novelist living in Albuquerque, New Mexico. After the United States army uses an alien DNA sequence to make a virus which infects almost everyone on Earth, Carol (whose wife Helen dies from the infection) ends up as one of 11 unaffected survivors in the whole world.

The infected are not killed, or turned into rabid zombies. They become entirely happy and helpful – seemingly harmless. Carol might be the last miserable person left alive.

Apocalypse as allegory

Just as the Body Snatchers films were read as metaphors for Cold War- and post-Watergate paranoia, Plur1bus almost asks to be read as allegory.

The Latin title means “many”, evoking the collective mass infected by the virus. However, Plur1bus more specifically calls to mind the motto of the United States: E pluribus unum – “out of many, one”.

Early reviews indicate a plurality of meanings, including a metaphor for contemporary loneliness, and an allegory of women’s oppression in abusive relationships.

In episode two, Carol tries to convince other survivors to oppose the hive mind – but at least one survivor wishes she could join them and become like everyone else.

Americans are politically polarised; those on opposites sides of the debate see their opponents as utterly other, or alien.

Perhaps Plur1bus offers a portrait of an individual seeking to escape a conformist mass. What is it like to believe something that sets you apart from the rest of the world?

An alien intelligence

Body Snatchers found horror in human figures stripped of any inner self. Instead, Gilligan packs Plur1bus with images of all human innerness and knowledge massed into a single entity. Each “individual” shares access to a synthesised totality of all memory, experience, understanding and skill.

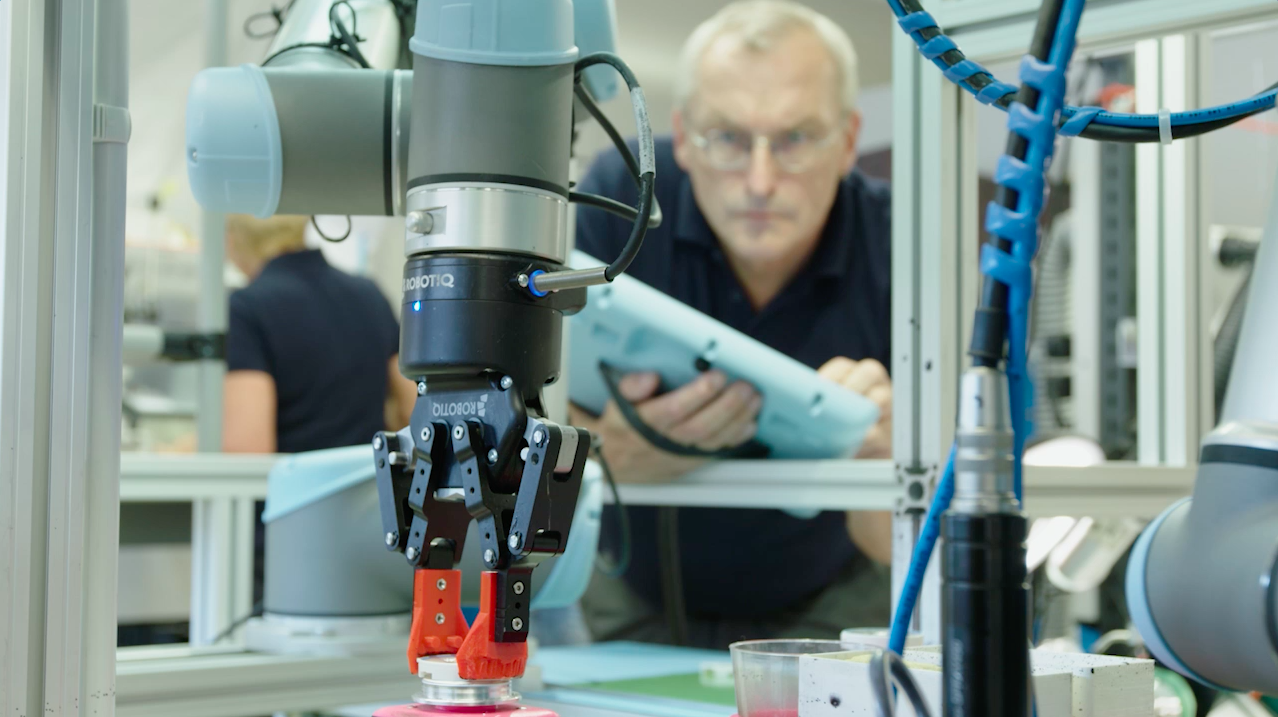

One of the show’s most thoroughgoing motifs lies in its images of humans working as machines, with all acts of knowledge or skill divorced from the individual persons in which they were developed.

Infected military scientists swipe petri dishes with metronomic perfection; a jetliner is piloted by a waitress from TGI Friday’s; a 9-year-old boy displays the knowledge and skills of a gynaecologist. Each person holds the secrets of everyone else’s mind, including Helen’s memories of Carol.

Whatever Gilligan planned when he conceived of the show, and wherever he takes it, its central structure has undeniable resonance with a world permeated by expressions of AI.

With the exception of Carol and a handful of fellow survivors, every character we see is, in a certain sense, no character at all – just the outer appearance of an individual, behind which lies a fabricated synthesis of everyone else.

There’s a haunting moment near the end of episode two: one of “them” appears anguished at her separation from Carol, and casts a longing look back as they part. This is also echoed at the opening of episode three with Carol’s impassive gaze at the northern lights, and a scene in which it is impossible to tell if we are seeing two pilots before or after the alien infection has taken hold.

What does it mean to be moved by signs of feeling which issue from a being that we suspect is not a person at all? What does it mean to outsource our expressions of self to an inhuman consciousness? What would we become?

Fortunately, with Plur1bus, we can appreciate a depth of inventive insight that remains, for now, only human.

The post “Vince Gilligan’s sci-fi series Plur1bus taps into our greatest fears about AI” by Elliott Logan, Lecturer in Film, Screen, and Culture, Monash University was published on 11/17/2025 by theconversation.com