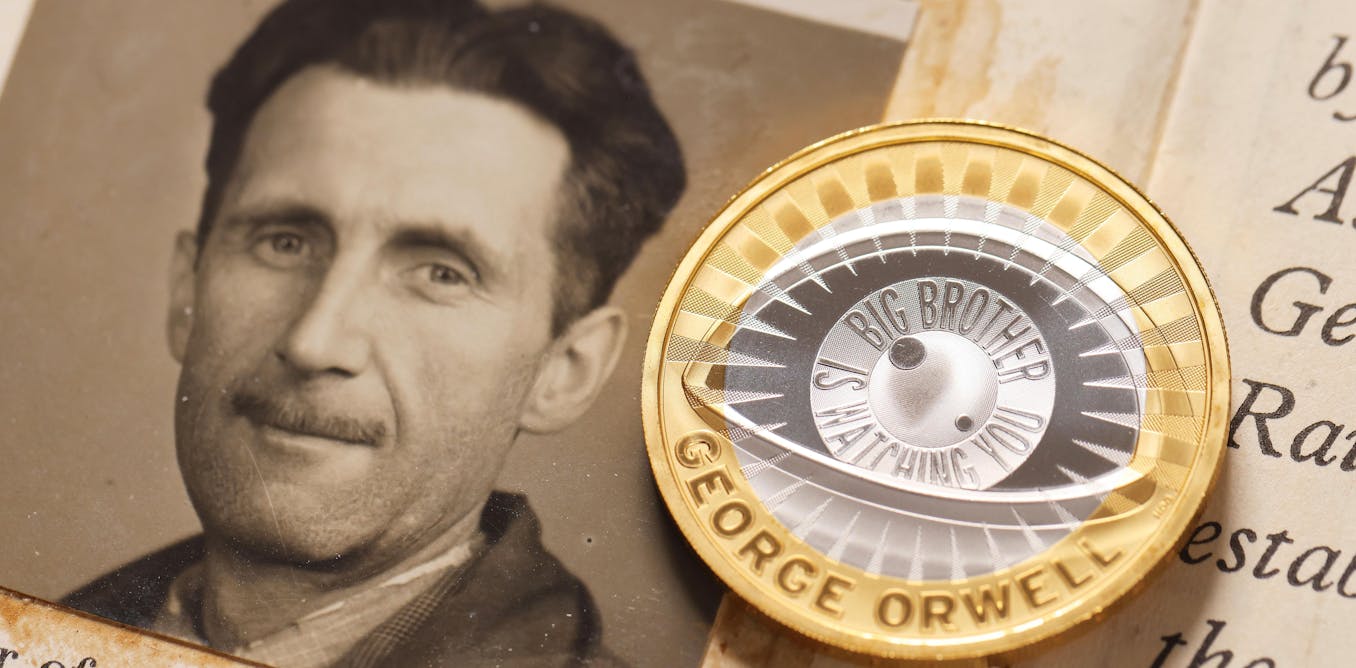

Companies developing AI models, such as OpenAI and Meta, train their systems on enormous datasets. These consist of text from newspapers, books (often sourced from unauthorised repositories), academic publications and various internet sources. The material includes works that are copyrighted.

The Atlantic magazine recently alleged Meta, parent company of Facebook and Instagram, had used LibGen, an illegal book repository, to train its generative AI tool. Created around 2008 by Russian scientists, LibGen hosts more than 7.5 million books and 81 million research papers, making it one of the largest online libraries of pirated work in the world.

The practice of training AI on copyrighted material has sparked intense legal debates and raised serious concerns among writers and publishers, who face the risk of their work being devalued or replaced.

While some companies, such as OpenAI, have established formal partnerships with some content providers, many publishers and writers have objected to their intellectual property being used without consent or financial compensation.

Author Tracey Spicer has described Meta’s use of copyrighted books as “peak technocapitalism”, while Sophie Cunningham, chair of the board of the Australian Society of Authors, has accused the company of “treating writers with contempt”.

Meta is being sued in the United States for copyright infringement by a group of authors, including Michael Chabon, Ta-Nehisi Coates and comedian Sarah Silverman. Court documents filed in January allege Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg approved the use of the LibGen dataset for training the company’s AI models knowing it contained pirated material. Meta has declined to comment on the ongoing court case.

The legal battles centre on a fundamental question: does mass data scraping for AI training constitute “fair use”?

Legal challenges

The stakes are particularly high, as AI companies not only train their models using publicly accessible data, but use the content to provide Chatbot answers that may compete with the original creators’ works.

AI companies defend their data scraping on the grounds of innovation and “fair use” – a legal doctrine that, in the US, permits “the unlicensed use of copyright-protected works in certain circumstances”. Those circumstances include research, teaching and commentary. Similar provisions apply in other legal jurisdictions, including Australia.

AI companies argue their use of copyrighted works for training purposes is transformative. But when AI can reproduce content that closely mimics an author’s style or regenerates substantial portions of copyrighted material, legitimate questions arise about whether this constitutes infringement.

A landmark legal case in this battle is The New York Times vs OpenAI and Microsoft. Launched in late 2023, the case is ongoing. The New York Times alleges copyright infringement, claiming OpenAI and its partner Microsoft used millions of its articles without permission, to train AI systems.

Although the scope of the lawsuit has been narrowed to core claims relating to copyright and trademark dilution infringement, a recent court decision allowing the case to proceed to trial has been seen as a win for the New York Times.

Other news publishers, including News Corp, have also initiated legal proceedings against AI companies.

The concern extends beyond traditional publishers and news organisations to individual creators, who face threats to their livelihoods. In 2023, a group of authors – including Jonathan Franzen, John Grisham and George R.R. Martin – filed a class-action suit, still unresolved, alleging OpenAI copied their works without permission or payment.

Alex Berliner/AAP

Implications

These and numerous other legal challenges will have significant implications for the future of the publishing and media industries, and for AI companies.

The issue is particularly alarming, considering that in 2023, the average median full-time income for an author in the United States was was just over USD$20,000. The situation is even more dire in Australia, where authors earn an average of AUD$18,200 per year.

In response to these challenges, the Australian Society of Authors (ASA) has called for the Australian government to regulate AI. Its proposal is that AI companies should be required to obtain permission before using copyrighted work and must provide fair compensation to writers who grant authorisation.

The ASA has also called for clear labelling of content that is wholly or partially AI generated, and transparency regarding which copyrighted works have been used for AI training and the purposes of that training.

If training AI on copyrighted works is permissible, what compensation model is fair to original creators?

In 2024, HarperCollins signed a deal allowing limited use of selected nonfiction backlist titles for AI training. The three-year non-exclusive agreement affected over 150 Australian authors. It gave them the choice to opt in for USD$2,500, split 50/50 between writer and publisher.

However, the Authors Guild argues a 50/50 split is not fair and recommends 75% should go to the author and only 25% to the publisher.

Potential responses

Publishers and creators are increasingly concerned about the loss of control of intellectual property. AI systems rarely cite sources, diminishing the value of attribution. If these systems can generate content that substitutes for published works, this has the potential to reduce demand for original content.

As AI-generated content floods the market, distinguishing and protecting original works becomes more challenging. Amazon has already been swamped by AI-generated content, including imitations and book summaries, sold as ebooks.

Lawmakers in various jurisdictions are considering updates to national copyright laws specifically addressing AI, which aim to promote innovation and safeguard rights. But the responses are diverging dramatically.

The European Union’s Artificial Intelligence Act of 2024 aims to balance copyright holders’ interests with innovation in AI development. The copyright provisions were added late in negotiations and are considered relatively weak. But they provide additional tools for copyright holders to identify potential infringements and give general purpose AI providers more legal certainty, if they comply with the rules.

Any plans to regulate AI have been explicitly rejected by US vice president JD Vance. In February, at the Artificial Intelligence Action Summit in Paris, Vance described “excessive regulation” as “authoritarian censorship” that undermined the development of AI.

This stance reflects the broader US approach to AI regulation. In their submissions to the US government’s AI Action Plan currently under development, both OpenAI and Google argue AI companies should be able to freely train their models on copyrighted material under the “fair use” principle, as part of “a copyright strategy that promotes the freedom to learn”.

This position raises significant concerns for content creators.

Virginia Murdoch/Text Publishing

Deal or no deal?

In addition to legal frameworks, various models are being developed globally to ensure creators and publishers are being paid, while allowing AI companies to use the data.

Since mid-2023, several academic publishers, including Informa (the parent company of Taylor & Francis), Wiley and Oxford University Press, have established licensing agreements with AI companies.

Other publishers are making direct deals with AI companies, along similar lines to HarperCollins. In Australia, Black Inc. recently asked its authors to sign opt-in agreements permitting the use of their work for AI training purposes.

A variety of licensing platforms, such as Created by Humans, have emerged. These aim to facilitate the legal use of copyrighted materials for AI training and clearly indicate to readers when a book is written by humans, not AI-generated.

To date, the Australian government has not enacted any specific statutes that would directly regulate AI. In September 2024, the government released a voluntary framework consisting of eight AI Ethics Principles, which call for transparency, accountability and fairness in AI systems.

The use of copyrighted works to train AI systems remains contested legal territory. Both AI developers and creators have valid interests at stake. There is a clear need to balance technological innovation with sustainable models for original content creation.

Finding the right balance between these interests will likely require a combination of legal precedent, new business models and thoughtful policy development.

As courts begin to rule on these cases, we may see clearer guidelines emerge about what constitutes fair use in AI training and AI-driven content creation, and what compensation models might be appropriate. Ultimately, the future of human creativity hangs in the balance.

The post “Meta allegedly used pirated books to train AI. Australian authors have objected, but US courts may decide if this is ‘fair use’” by Agata Mrva-Montoya, Senior Lecturer, Department of Media and Communications, University of Sydney was published on 04/01/2025 by theconversation.com