When the New Scientist revealed that it had obtained a UK government minister’s ChatGPT prompts through a freedom of information (FOI) request, many in journalism and politics did a double take. Science and technology minister Peter Kyle had apparently asked the AI chatbot to draft a speech, explain complex policy and – more memorably – tell him what podcasts to appear on.

What once seemed like private musings or experimental use of AI is now firmly in the public domain – because it was done on a government device.

It’s a striking example of how FOI laws are being stretched in the age of artificial intelligence. But it also raises a bigger, more uncomfortable question: what else in our digital lives counts as a public record? If AI prompts can be released, should Google searches be next?

Britain’s Freedom of Information Act was passed in 2000 and came into force in 2005. Two distinct uses of FOI have since emerged. The first – and arguably the most successful – is FOI applied to personal records. This has given people the right to access information held about them, from housing files to social welfare records. It’s a quiet success story that has empowered citizens in their dealings with the state.

The second is what journalists use to interrogate the workings of government. Here, the results have been patchy at best. While FOI has produced scoops and scandals, it’s also been undermined by sweeping exemptions, chronic delays and a Whitehall culture that sees transparency as optional rather than essential.

Tony Blair, who introduced the Act as prime minister, famously described it as the biggest mistake of his time in government. He later argued that FOI turned politics into “a conversation conducted with the media”.

Successive governments have chafed against FOI. Few cases illustrate this better than the battle over the black spider memos – letters written by the then Prince (now King) Charles to ministers, lobbying on issues from farming to architecture. The government fought for a decade to keep them secret, citing the prince’s right to confidential advice.

Read more:

Dull content, but the release of Prince Charles letters is a landmark moment

When they were finally released in 2015 after a Supreme Court ruling, the result was mildly embarrassing but politically explosive. It proved that what ministers deem “private” correspondence can, and often should, be subject to public scrutiny.

The ChatGPT case feels like a modern version of that debate. If a politician drafts ideas via AI, is that a private thought or a public record? If those prompts shape policy, surely the public has a right to know.

Are Google searches next?

FOI law is clear on paper: any information held by a public body is subject to release unless exempt. Over the years, courts have ruled that the platform is irrelevant. Email, WhatsApp or handwritten notes – if the content relates to official business and is held by a public body, it’s potentially disclosable.

The precedent was set in Dublin in 2017 when the Irish prime minister’s office released WhatsApp messages to the public service broadcaster RTÉ. The UK’s Information Commissioner’s Office has also published detailed guidance confirming that official information held in non-corporate channels such as private email, WhatsApp or Signal is subject to FOI requests if it relates to public authority business.

The ongoing COVID-19 inquiry has shown how WhatsApp groups – once considered informal backchannels – became key decision-making arenas in government, with messages from Boris Johnson, Matt Hancock and senior advisers like Dominic Cummings now disclosed as official records.

In Australia, WhatsApp messages between ministers were scrutinised during the Robodebt scandal, an illegal welfare hunt that ran from 2016-19, while Canada’s inquiry into the “Freedom Convoy” protests in 2022 revealed texts and private chats between senior officials as crucial evidence of how decisions were made.

The principle is simple: if government work is being done, the public has a right to see it.

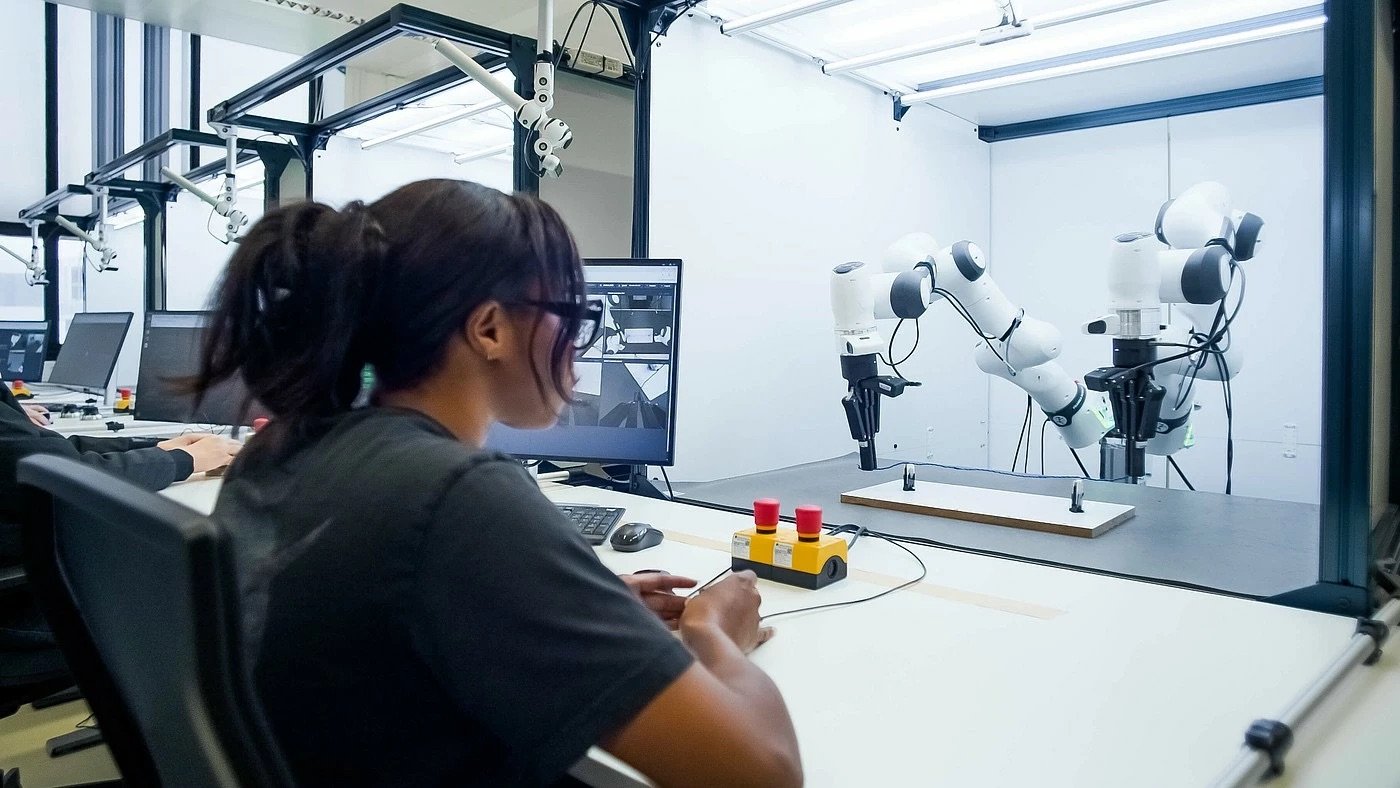

AI chat logs now fall into this same grey area. If an official or minister uses ChatGPT to explore policy options or draft a speech on a government device, that log may be a record — as Peter Kyle’s prompts proved.

Andy Rain/EPA-EFE

This opens a fascinating (and slightly unnerving) precedent. If AI prompts are FOI-able, what about Google searches? If a civil servant types “How to privatise the NHS” into Chrome on a government laptop, is that a private query or an official record?

The honest answer is: we don’t know (yet). FOI hasn’t fully caught up with the digital age. Google searches are usually ephemeral and not routinely stored. But if searches are logged or screen-captured as part of official work, then they could be requested.

Similarly, what about drafts written in AI writing assistant Grammarly or ideas brainstormed with Siri? If those tools are used on official devices, and the records exist, they could be disclosed.

Of course, there’s nothing to stop this or any future government from changing the law or tightening FOI rules to exclude material like this.

FOI, journalism and democracy

While these kinds of disclosures are fascinating, they risk distracting from a deeper problem: FOI is increasingly politicised. Refusals are now often based on political considerations rather than the letter of the law, with requests routinely delayed or rejected to avoid embarrassment. In many cases, ministers’ use of WhatsApp groups was a deliberate attempt to avoid scrutiny in the first place.

There is a growing culture of transparency avoidance across government and public services – one that extends beyond ministers. Private companies delivering public contracts are often shielded from FOI altogether. Meanwhile, some governments, including Ireland and Australia, have weakened the law itself.

AI tools are no longer experiments, they are becoming part of how policy is developed and decisions are made. Without proper oversight, they risk becoming the next blind spot in democratic accountability.

For journalists, this is a potential game changer. Systems like ChatGPT may soon be embedded in government workflows, drafting speeches, summarising reports and even brainstorming strategy. If decisions are increasingly shaped by algorithmic suggestions, the public deserves to know how and why.

But it also revives an old dilemma. Democracy depends on transparency – yet officials must have space to think, experiment and explore ideas without fear that every AI query or draft ends up on the front page. Not every search or chatbot prompt is a final policy position.

Blair may have called FOI a mistake, but in truth, it forced power to confront the reality of accountability. The real challenge now is updating FOI for the digital age.

The post “Why a journalist could obtain a minister’s ChatGPT prompts – and what it means for transparency” by Tom Felle, Associate Professor of Journalism, University of Galway was published on 03/19/2025 by theconversation.com