The roll-out of the European Union’s Artificial Intelligence Act has hit a critical turning point. The act establishes rules for how AI systems can be used within the European Union. It officially entered into force on August 1 2024, although different rules come into effect at different times.

The European Commission has now proposed delaying parts of the act until 2027. This follows intense pressure from tech companies and from the Trump administration.

Rules contained in the act are based around the risk posed by an AI system. For example, high risk AI is required to be very accurate and be overseen by a human. This was to apply to companies developing high-risk AI systems posing “serious risks to health, safety or fundamental rights” from August 2026 or a year later. But now organisations deploying these technologies, whose purposes would include analysing CVs or assessing loan applications, will now not come under the bill’s provisions until December 2027.

The proposed delay is part of an overhaul of EU digital rules, including privacy regulations and data legislation. The new rules could benefit businesses, including American tech giants, with critics calling them a “rollback” of digital protections. The EU says its “simpler” rules would help “European companies to grow and to stay at the forefront of technology while at the same time promoting Europe’s highest standards of fundamental rights, data protection, safety and fairness”.

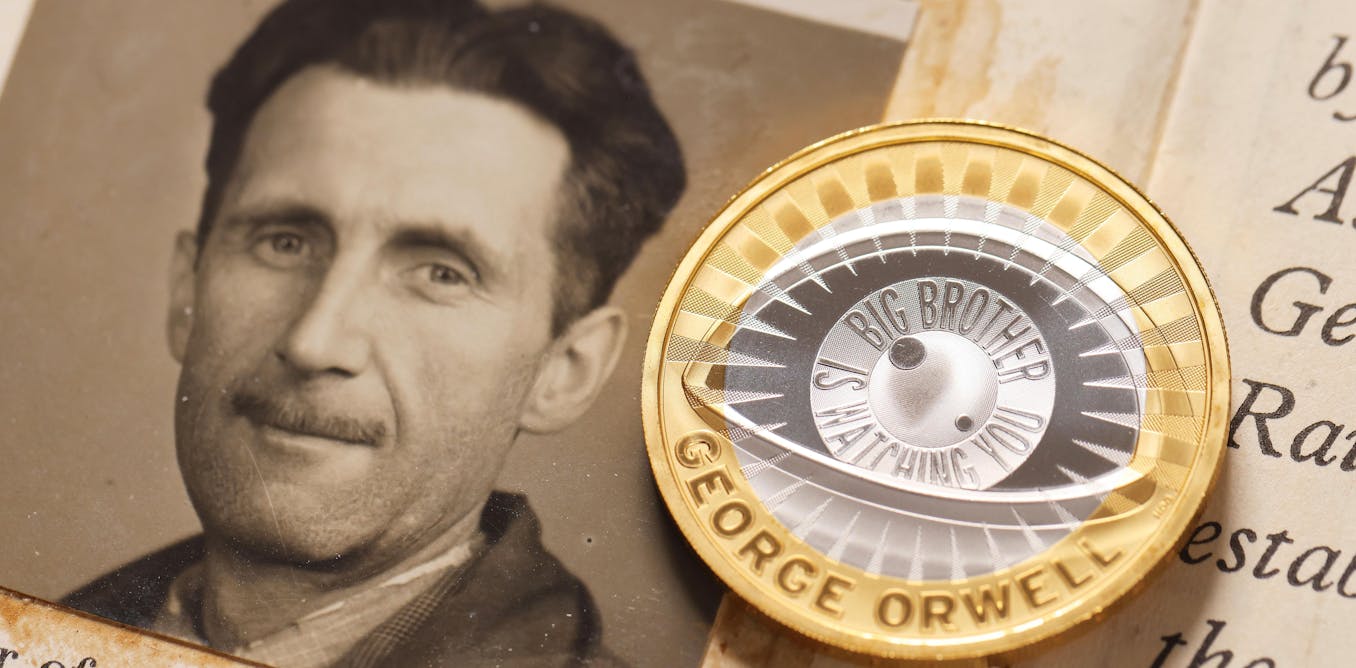

The negative reaction to the proposals exposes transatlantic fault lines over how to effectively govern the use of AI. The first international speech by Vice President JD Vance in February 2024 offers a useful insight into the current US admininstration’s attitudes towards AI regulation.

Migma_Agency

Vance claimed that excessive regulation of the sector could “kill a transformative industry just as it’s taking off”. He also took aim at EU regulations that are relevant to AI such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and Digital Services Act (DSA). He said that for smaller firms, “navigating the GDPR means paying endless legal compliance costs”.

He added that the DSA created a burden for tech companies, forcing them to take down content and police “so-called misinformation”. Vance further pledged that the US would not accept “foreign governments … tightening the screws” on American tech companies.

On the offensive

By August of this year, the Trump administration had launched its own AI policy offensive, including a plan to accelerate AI innovation and national AI infrastructure. It announced executive orders to streamline data infrastructure, promote the export of American AI technologies and prevent what the administration sees as the potential for bias in federal AI procurement and standards.

It also sought deregulation, open-source development (where the code for AI systems is available to developers) and “neutrality”. The last of these appears to mean resisting what the White House sees as “woke” or restrictive governance models.

Additionally, President Trump has criticised the EU’s Digital Services Act, threatening additional tariffs in response to further fines or restrictions on US tech companies. EU responses varied. While some policymakers were reportedly shocked, others reminded US leaders that EU rules apply equally to all companies, regardless of origin.

So how can this gap over AI policy be bridged? In March 2025, a group of interdisciplinary US and German scholars – ranging in disciplines from computer science to philosophy – gathered at the University of North Carolina in the town of Chapel Hill. Their aims were to tackle a series of questions about the state of transatlantic AI governance and to make sense of evolving tech negotiations between the US and EU.

The recommendations from the meeting were summarised in a policy paper. The scholars saw the combination of US innovation strengths and EU human rights protections as key to meeting the urgent challenges of designing AI systems that benefit society.

The policy paper said: “The interconnected nature of AI development makes isolated regulatory approaches insufficient. AI systems are deployed globally, and their impacts ripple through international markets and societies.”

Major challenges identified in the paper include algorithmic bias (where AI based systems favour certain sections of society or individuals), privacy protection and labour market disruption (including but not limited to intellectual property theft). Also mentioned were the concentration of technological power and adverse environmental consequences from all the energy required.

Based on human rights and social justice principles, the policy paper made a series of recommendations that range from clear guidelines for ethical AI deployment in the workplace to mechanisms for safeguarding reliable information, and preventing potential pressure on academic researchers to support particular viewpoints.

Ultimately, the goal is a democratic and sustainable AI that is developed, deployed, and governed in ways that uphold values like public participation, transparency and accountability.

To achieve that, policy and regulation must strike a difficult balance between innovation and fairness. These variables are not mutually exclusive. For this all to work, they must co-exist. It’s a task that will require transatlantic partners to lead together, as they have for the better part of the last century.

The post “EU proposal to delay parts of its AI Act signal a policy shift that prioritises big tech over fairness” by Jessica Heesen, Head of Research Group, media ethics, philosophy of technology & AI, International Center for Ethics in the Sciences and Humanities (IZEW), University of Tübingen was published on 11/24/2025 by theconversation.com