There have been several headlines over the past week about an AI chatbot officially passing the Turing test.

These news reports are based on a recent preprint study by two researchers at the University of California San Diego in which four large language models (LLMs) were put through the Turing test. One model – OpenAI’s GPT-4.5 – was deemed indistinguishable from a human more than 70% of the time.

The Turing test has been popularised as the ultimate indicator of machine intelligence. However, there is disagreement about the validity of this test. In fact, it has a contentious history which calls into question how effective it really is at measuring machine intelligence.

So what does this mean for the significance of this new study?

What did the study find?

The preprint study by cognitive scientists Cameron Jones and Benjamin Bergen was published in March, but has not yet been peer-reviewed. It tested 4 LLMs: ELIZA, GPT-4o, LLaMa-3.1-405B, and GPT-4.5.

The tests consisted of participants completing eight rounds of conversations in which they acted as an interrogator exchanging text messages with two witnesses simultaneously. One witness was a human and the other an LLM. Some 284 participants were randomly assigned to be either the interrogator or the witness.

Participants were required to interact with both witnesses simultaneously across a split screen for five minutes, with the test interface mimicking that of a conventional messaging interface. Following this interaction, they decided which witness was a human, and which was an AI chatbot.

Participants judged GPT-4.5 to be the human 73% of the time, and LLaMa-3.1-405B to be the human 56% of the time. The other two models (ELIZA and GPT-4o) only fooled participants 23% and 21% of the time respectively.

Ascannio/Shutterstock

What exactly is the Turing Test?

The first iteration of the Turing test was presented by English mathematician and computer scientist Alan Turing in a 1948 paper titled “Intelligent Machinery”. It was originally proposed as an experiment involving three people playing chess with a theoretical machine referred to as a paper machine, two being players and one being an operator.

In the 1950 publication “Computing Machinery and Intelligence”, Turing reintroduced the experiment as the “imitation game” and claimed it was a means of determining a machine’s ability to exhibit intelligent behaviour equivalent to a human. It involved three participants: Participant A was a woman, participant B a man and participant C either gender.

Through a series of questions, participant C is required to determine whether “X is A and Y is B” or “X is B and Y is A”, with X and Y representing the two genders.

Elliott & Fry/Wikipedia

A proposition is then raised: “What will happen when a machine takes the part of A in this game? Will the interrogator decide wrongly as often when the game is played like this as he does when the game is played between a man and a woman?”

These questions were intended to replace the ambiguous question, “Can machines think?”. Turing claimed this question was ambiguous because it required an understanding of the terms “machine” and “think”, of which “normal” uses of the words would render a response to the question inadequate.

Over the years, this experiment was popularised as the Turing test. While the subject matter varied, the test remained a deliberation on whether “X is A and Y is B” or “X is B and Y is A”.

Why is it contentious?

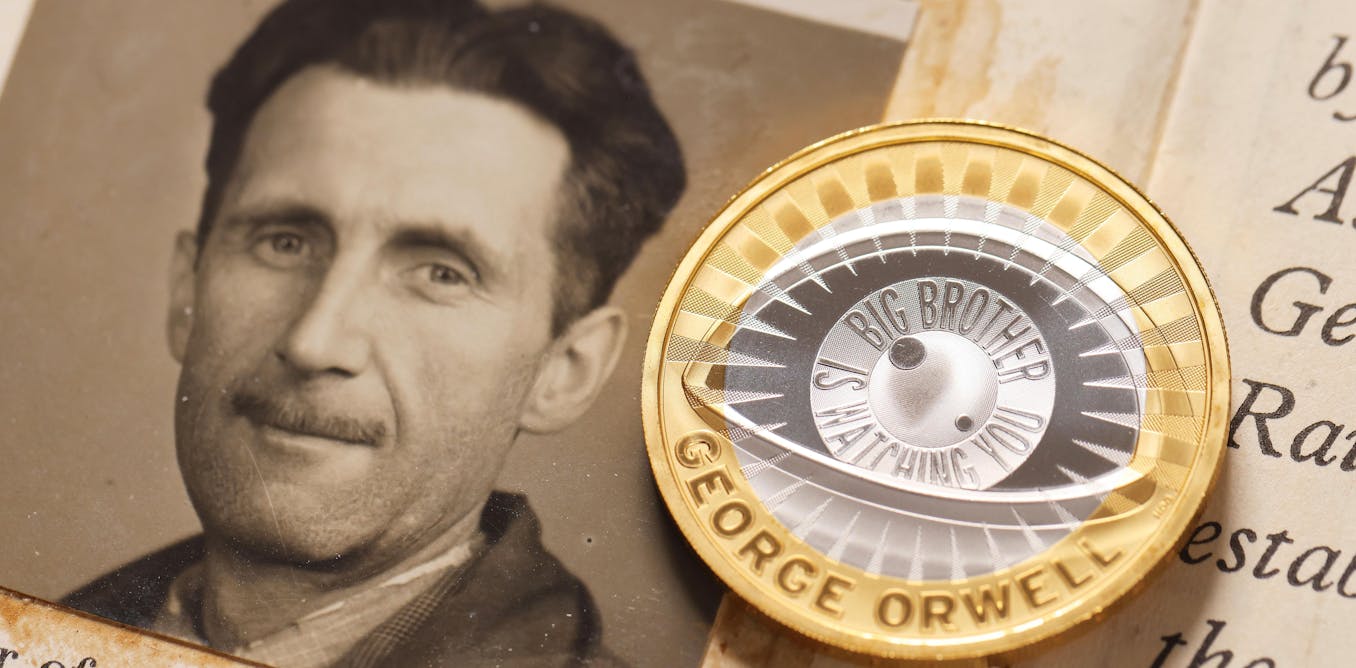

While popularised as a means of testing machine intelligence, the Turing test is not unanimously accepted as an accurate means to do so. In fact, the test is frequently challenged.

There are four main objections to the Turing test:

- Behaviour vs thinking. Some researchers argue the ability to “pass” the test is a matter of behaviour, not intelligence. Therefore it would not be contradictory to say a machine can pass the imitation game, but cannot think.

- Brains are not machines. Turing makes assertions the brain is a machine, claiming it can be explained in purely mechanical terms. Many academics refute this claim and question the validity of the test on this basis.

- Internal operations. As computers are not humans, their process for reaching a conclusion may not be comparable to a person’s, making the test inadequate because a direct comparison cannot work.

- Scope of the test. Some researchers believe only testing one behaviour is not enough to determine intelligence.

fizkes/Shutterstock

So is an LLM as smart as a human?

While the preprint article claims GPT-4.5 passed the Turing test, it also states:

the Turing test is a measure of substitutability: whether a system can stand-in for a real person without […] noticing the difference.

This implies the researchers do not support the idea of the Turing test being a legitimate indication of human intelligence. Rather, it is an indication of the imitation of human intelligence – an ode to the origins of the test.

It is also worth noting that the conditions of the study were not without issue. For example, a five minute testing window is relatively short.

In addition, each of the LLMs was prompted to adopt a particular persona, but it’s unclear what the details and impact of the “personas” were on the test.

For now it is safe to say GPT-4.5 is not as intelligent as humans – although it may do a reasonable job of convincing some people otherwise.

The post “ChatGPT just passed the Turing test. But that doesn’t mean AI is now as smart as humans” by Zena Assaad, Senior Lecturer, School of Engineering, Australian National University was published on 04/08/2025 by theconversation.com