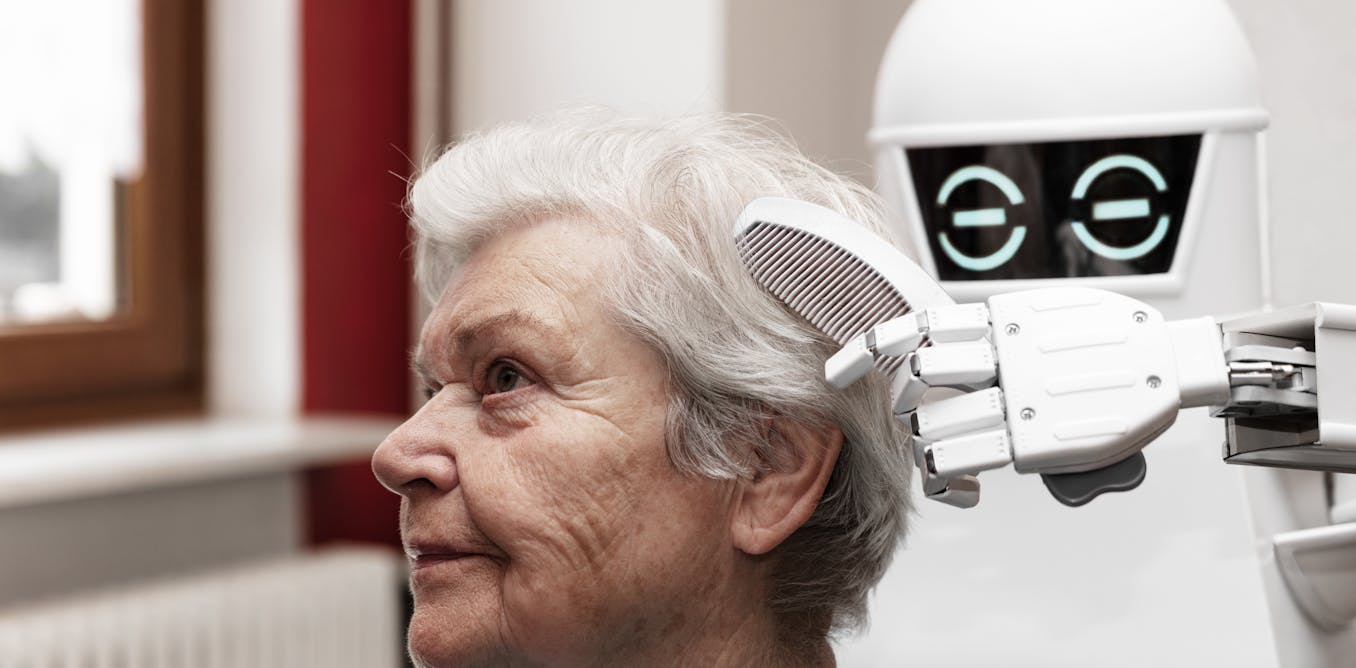

As more of us live longer, can robots help us maintain healthier, more independent and dignified lives? The robots I’ve been studying are friendly, helpful machines that can talk, remind, monitor – and even offer a form of companionship for older people.

By 2050, the global population of adults aged 60 and above is projected to surpass 2 billion, posing significant health, social and economic challenges worldwide. As people age, they often experience a gradual decline in both physical and cognitive capabilities, which can threaten their ability to live independently.

Daily tasks such as cooking, managing medications or simply getting up from a chair become more difficult, especially for people with mobility impairments or those living in environments that lack adequate support – such as poor housing, limited access to transport, or underfunded healthcare services.

Supporting older adults to maintain autonomy in daily life should be one of the most pressing goals of modern healthcare systems, particularly as the demand for care increasingly outweighs available resources.

Get your news from actual experts, straight to your inbox. Sign up to our daily newsletter to receive all The Conversation UK’s latest coverage of news and research, from politics and business to the arts and sciences.

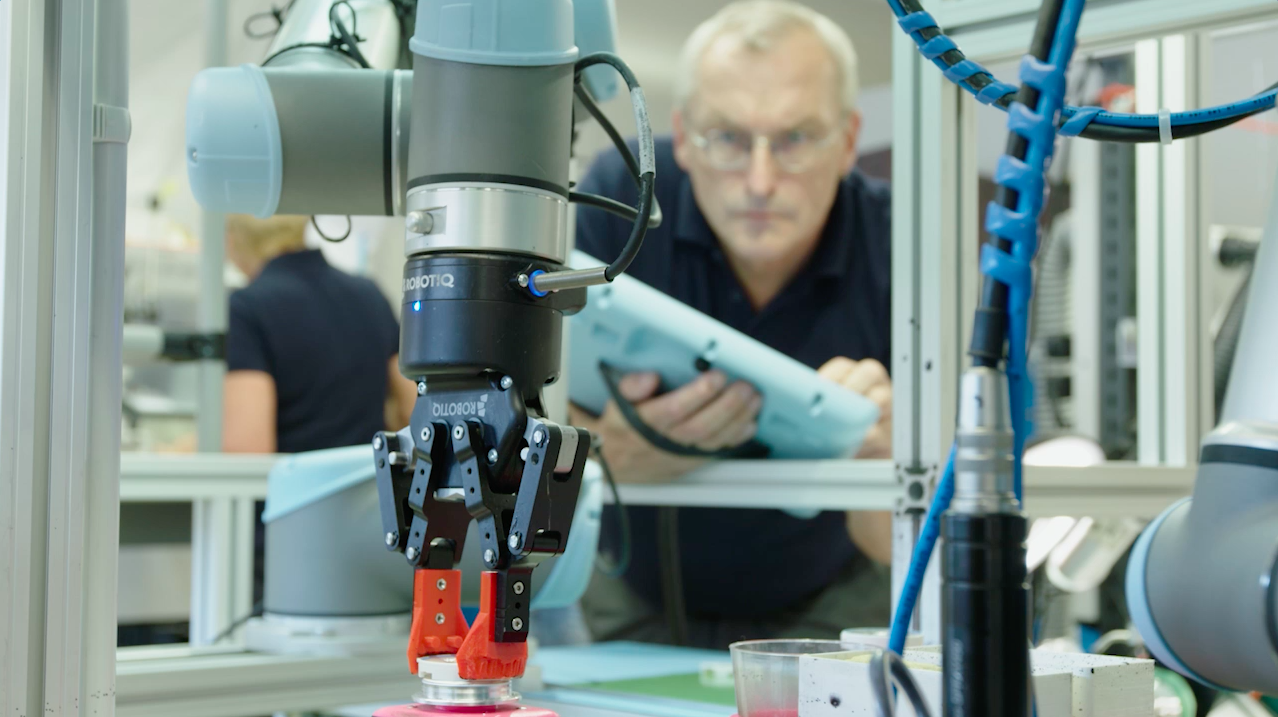

My research at Nottingham Trent University, in collaboration with colleagues at Sheffield Hallam University and Loughborough University, explored how socially assistive robots – often resembling a human or pet – and other monitoring technologies can support older people at home to maintain their independence without needing traditional human care.

In our research, we spoke to older adults from diverse backgrounds, including people with physical disabilities and those on lower incomes. Many were open to the idea of a robot at home, particularly if it could be personalised, affordable and easy to use. They often welcomed the potential for socially assistive robots and home sensors to help them stay active and independent.

Robots can remind us to move around, take medication, or contact a friend. For those with physical impairments, they can assist with tasks that require strength or grip, such as lifting shopping bags or opening jars.

But the picture isn’t all rosy. A tool meant to help can backfire if it’s too demanding or poorly designed.

In our follow-up study, we looked at how people interact with a robot while completing everyday thinking tasks such as following instructions or solving puzzles. One example is the trail-making test, a tool often used to assess how well someone can pay attention, process information quickly, and switch between different mental tasks. These are all skills we rely on in daily life – whether it’s navigating public transport, cooking from a recipe, or managing bills.

We found the robot improved a person’s performance and reduced how mentally taxing the task felt, but only up to a point. When the robot gave too much information at once, people became overwhelmed. This highlights a crucial finding: robots must be designed with the user’s cognitive abilities and limits in mind.

Our interviewees also raised valid concerns about cost – “how would we afford this?” – as well as privacy, asking: “What data is being collected?” Usability was another worry: “What if it breaks?” or “what if I don’t know how to use it?” Some were uneasy about robots making people more passive, or even replacing important human interaction.

Still, many were open to the idea, especially if the robot could be personalised, affordable and helpful. Our research highlights that older people value these robots more when they offer emotional connection, not just practical support.

Designing for real people

One-size-fits-all technology will not work. An older adult with arthritis and a low income may need something very different from a tech-savvy retiree in good health.

So, successful introduction of this technology depends on co-designing it with older adults, not just for them. This includes everything from ensuring that robots have intuitive interfaces, to making sure they can physically navigate a cramped living room, to ensuring they respect privacy and consent.

There’s no doubt that helpful technologies including home robots that offer reminders, support, or companionship will be an important part of how we care for our ageing population in the years to come.

But for them to work, we need more than clever engineering. We need empathy, inclusion and a deeper understanding of what it means to age well. That means listening to older adults, testing technologies in real-life settings, and designing for both mind and body.

Growing older should not mean growing isolated or inactive. If we get it right, a robot might not just help you remember your pills. It might help you keep your independence.

The post “Can a robot help you age better?” by Daniele Magistro, Associate Professor in Physical Activity and Health, Department of Sport Science, Nottingham Trent University was published on 06/06/2025 by theconversation.com