In my writing and rhetoric courses, students have plenty of opinions on whether AI is intelligent: how well it can assess, analyze, evaluate and communicate information.

When I ask whether artificial intelligence can “think,” however, I often look upon a sea of blank faces. What is “thinking,” and how is it the same or different from “intelligence”?

We might treat the two as more or less synonymous, but philosophers have marked nuances for millennia. Greek philosophers may not have known about 21st-century technology, but their ideas about intellect and thinking can help us understand what’s at stake with AI today.

The divided line

Although the English words “intellect” and “thinking” do not have direct counterparts in the ancient Greek, looking at ancient texts offers useful comparisons.

In “Republic,” for example, Plato uses the analogy of a “divided line” separating higher and lower forms of understanding.

Wikimedia Commons

Plato, who taught in the fourth century BCE, argued that each person has an intuitive capacity to recognize the truth. He called this the highest form of understanding: “noesis.” Noesis enables apprehension beyond reason, belief or sensory perception. It’s one form of “knowing” something – but in Plato’s view, it’s also a property of the soul.

Lower down, but still above his “dividing line,” is “dianoia,” or reason, which relies on argumentation. Below the line, his lower forms of understanding are “pistis,” or belief, and “eikasia,” imagination.

Pistis is belief influenced by experience and sensory perception: input that someone can critically examine and reason about. Plato defines eikasia, meanwhile, as baseless opinion rooted in false perception.

In Plato’s hierarchy of mental capacities, direct, intuitive understanding is at the top, and moment-to-moment physical input toward the bottom. The top of the hierarchy leads to true and absolute knowledge, while the bottom lends itself to false impressions and beliefs. But intuition, according to Plato, is part of the soul, and embodied in human form. Perceiving reality transcends the body – but still needs one.

So, while Plato does not differentiate “intelligence” and “thinking,” I would argue that his distinctions can help us think about AI. Without being embodied, AI may not “think” or “understand” the way humans do. Eikasia – the lowest form of comprehension, based on false perceptions – may be similar to AI’s frequent “hallucinations,” when it makes up information that seems plausible but is actually inaccurate.

Embodied thinking

Aristotle, Plato’s student, sheds more light on intelligence and thinking.

sailko/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

In “On the Soul,” Aristotle distinguishes “active” from “passive” intellect. Active intellect, which he called “nous,” is immaterial. It makes meaning from experience, but transcends bodily perception. Passive intellect is bodily, receiving sensory impressions without reasoning.

We could say that these active and passive processes, put together, constitute “thinking.” Today, the word “intelligence” holds a logical quality that AI’s calculations may conceivably replicate. Aristotle, however, like Plato, suggests that to “think” requires an embodied form and goes beyond reason alone.

Aristotle’s views on rhetoric also show that deliberation and judgment require a body, feeling and experience. We might think of rhetoric as persuasion, but it is actually more about observation: observing and evaluating how evidence, emotion and character shape people’s thinking and decisions. Facts matter, but emotions and people move us – and it seems questionable whether AI utilizes rhetoric in this way.

Finally, Aristotle’s concept of “phronesis” sheds further light on AI’s capacity to think. In “Nicomachean Ethics,” he defines phronesis as “practical wisdom” or “prudence.” “Phronesis” involves lived experience that determines not only right thought, but also how to apply those thoughts to “good ends,” or virtuous actions. AI may analyze large datasets to reach its conclusions, but “phronesis” goes beyond information to consult wisdom and moral insight.

‘Thinking’ robots?

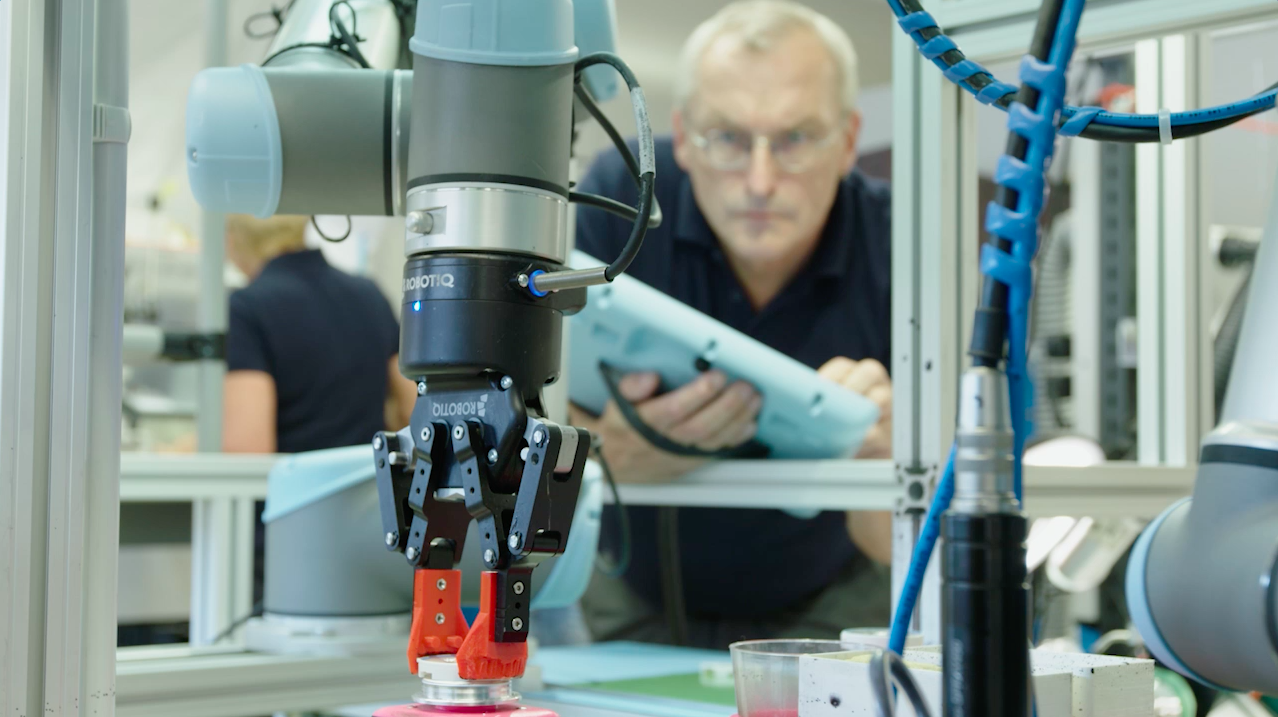

Today, AI takes on many physical forms, from autonomous vehicles and humanoid robots to health care robots and drones. If intelligence requires embodiment, as Plato and Aristotle believed, it might seem as if AI is coming closer than ever to human thinking.

AI does take on many forms, but they’re still not bodies; they run on code, algorithms and datasets. Intuitive understanding, emotion, integrity and practical wisdom seem to require an embodied, perishable form that is moved by experience.

Perhaps we should ask AI itself – so I did. When I prompted ChatGPT with the simple question, “Can you think?” it responded: “I can process information, analyze patterns, and generate responses based on data. So in some ways, it might ‘seem’ like I’m thinking. But it’s not thinking like a human does. I don’t have consciousness, emotions, intentions, or awareness. Everything I ‘do’ is based on patterns learned from huge amounts of text and a set of rules and probabilities. I can ‘simulate’ certain aspects of thinking, but I don’t truly think or understand in the human sense.”

That response aligns with Plato and Aristotle’s views. For now.

The post “Can AI think – and should it? What it means to think, from Plato to ChatGPT” by Ryan Leack, Assistant Professor of Writing, USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences was published on 07/18/2025 by theconversation.com