“We have copyright laws,” said arts minister Tony Burke last week. “We have no plans, no intention, no appetite to be weakening those copyright laws based on this draft report that’s floating around.”

He was referring to the Productivity Commission’s controversial floating of a text and data mining exception to the Australian Copyright Act, which would make it legal to train artificial intelligence (AI) large language models, such as ChatGPT, on copyrighted Australian work.

In the internet age, all that is solid melts into data, easily copied and distributed instantly across the internet. This includes the work of authors, songwriters and artists, ostensibly protected by the law of copyright.

“The rampant opportunism of big tech aiming to pillage other people’s work for their own profit is galling and shameful,” songwriter, author and former arts minister Peter Garrett told the Australian last week, in response to the Productivity Commission’s report.

He urged the federal government

to urgently strengthen copyright laws to help preserve cultural sovereignty and our valuable intellectual property in the face of powerful corporate forces who want to strip mine it and pay nothing.

I have researched how piracy, illegal streaming and remix culture violate these rights. Somehow, authors and artists have survived over 25 years of it. But AI poses a new threat.

Jason O’Brien/AAP

AI companies pushing against copyright

“You can’t be expected to have a successful AI program when every single article, book, or anything else that you’ve read or studied, you’re supposed to pay for,” United States president Donald Trump said at an AI Summit last month, launching his government’s AI Action Plan.

On July 23, he signed a trio of executive orders, including one on preventing “woke” AI in the US government, one on deregulating AI development (including removing environmental protections that could hamper the construction of data centres) and another on promoting the export of American AI technology.

Major AI companies, including Google and Microsoft, have put the copyright exemption argument to the Australian government.

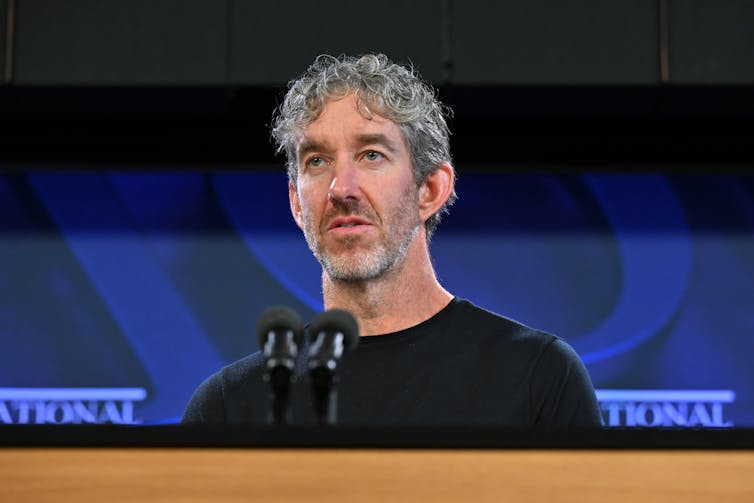

Australian tech billionaire Scott Farquhar, co-founder of software company Atlassian and chair of the Tech Council of Australia, said in a National Press Club address on 30 July that our “outdated” copyright laws are a barrier for AI companies wanting to train or host their models here.

He explicitly called for a text and data mining exception like the one the Productivity Commission is floating.

Julia Demaree Nikhinson/AAP

What is an author?

In the early 19th century, English poet and literary critic Samuel Taylor Coleridge defined the poet – or creative author – as an elevated representative of the human race: a cultural hero worthy of the highest respect. The genius author was a divinely inspired creator of completely original works. And the best way to understand the meaning of a work was to determine the author’s intention in creating it.

Tech companies promise their advanced AI systems are capable of creating new creative works. But for most of us, we read to find truths about humanity, or reflections of it.

“The interaction in your own mind, is very much with the author,” reflected arts minister Burke last week.

Roland Barthes, in his 1968 essay The Death of the Author argued language itself, in its constant flux and change, is what generates new work. He proposed a new model for the author: a scriptor, or copyist, who mixes writings, none of them original, so a new work is a “tissue of quotations” drawn from the “immense dictionary” of language. Ironically, in this way, Barthes predicted AI.

Read more:

Roland Barthes declared the ‘death of the author’, but postcolonial critics have begged to differ

Jane Dempster/AAP

A shift in wealth

Established in the 18th century, copyright enabled an author, songwriter or artist to make a living from royalties. It was meant to protect authors from illegal copying of their works.

The 21st century marked a massive shift in the wealth generated by creativity. Authors, and especially songwriters, suffered an enormous loss of revenue in the period 2000-2015, due to online piracy. In 1999, global revenue for the music industry was US$39 billion; in 2014, that figure fell to $15 billion.

At the same time, the owners of online platforms and big tech companies – who benefited from clicks to pirate sites offering works stolen from artists – enjoyed soaring profits. Google’s annual revenue jumped from US$0.4 billion in 2002 to $74.5 billion in 2015.

Several author and publisher lawsuits are underway regarding the unauthorised use of books by to train large language models. In June, a US federal judge ruled Anthropic did not breach copyright in using books to train its model, comparing the process to a “reader aspiring to be a writer”.

Copyright law reformers in the US have proposed that because all creativity is algorithmic, involving the novel combination of words, images or sounds, then an AI model, which uses algorithms to generate new works, should have its works protected by copyright. This would raise AI-as-author to the same legal status as human authors. These reformers believe rejecting this argument betrays an anthropocentric or “speciesist” bias.

If AI models were legally accepted as authors, this would represent another blow to the esteem accorded human authors.

Mick Tsikas/AAP

‘Erasure disguised as efficiency’

An AI model may be capable of generating works of fiction, but these works will be poor imitations of human creativity. The missing element: emotion. Works of fiction come from an author’s lifetime of experiences, from joy to grief, and the work engages readers or viewers on an emotional level.

The emotional capacity of an AI model: zero.

I have seen some atrocious AI-generated non-fiction books for sale on Amazon. The tell-tale signs are: no author byline, and sentences such as: “Since my dataset has not been updated since 2023, I cannot provide information past that date.” If someone buys those books, the publisher and Amazon will profit. No royalties will be paid to an author.

This is happening in other media, too. In the Hollywood Reporter last month, British producer Remy Blumenfeld told of a “showrunner with multiple global hits” being asked to rewrite a pilot generated by ChatGPT. He called it “erasure disguised as efficiency”.

In January, the US Authors Guild introduced an official certification system, for use by its members, to indicate that a book is human written. In April, the European Writers Council also called for “an effective transparency obligation for AI-generated products that clearly distinguishes them from the works made by human beings”.

In 2025, readers still flock to writers’ festivals, and we still esteem great authors as cultural heroes. But this status is threatened by AI. We must resist the possibility that human authors become mere content in AI systems’ datasets.

The ultimate degradation would be for authors to become unwilling data donors to AI. Big tech must be opposed in that ambition.

The post “AI companies want copyright exemption, but the arts minister says there are ‘no plans’ to weaken these laws. What’s going on?” by John Potts, Professor of Media, Macquarie University was published on 08/13/2025 by theconversation.com