A new nationally representative survey has revealed Australians are deeply concerned about the risks posed by artificial intelligence (AI). They want the government to take stronger action to ensure its safe development and use.

We conducted the survey in early 2024 and found 80% of Australians believe preventing catastrophic risks from advanced AI systems should be a global priority on par with pandemics and nuclear war.

As AI systems become more capable, decisions about how we develop, deploy and use AI are now critical. The promise of powerful technology may tempt companies – and countries – to race ahead without heeding the risks.

Our findings also reveal a gap between the AI risks that media and government tend to focus on, and the risks Australians think are most important.

Read more:

Demand for computer chips fuelled by AI could reshape global politics and security

Public concern about AI risks is growing

The development and use of increasingly powerful AI is still on the rise. Recent releases such as Google’s Gemini and Anthropic’s Claude 3 have seemingly near-human level capabilities in professional, medical and legal domains.

But the hype has been tempered by rising levels of public and expert concern. Last year, more than 500 people and organisations made submissions to the Australian government’s Safe and Responsible AI discussion paper.

They described AI-related risks such as biased decision making, erosion of trust in democratic institutions through misinformation, and increasing inequality from AI-caused unemployment.

Some are even worried about a particularly powerful AI causing a global catastrophe or human extinction. While this idea is heavily contested, across a series of three large surveys, most AI researchers judged there to be at least a 5% chance of superhuman AI being “extremely bad (e.g., human extinction)”.

The potential benefits of AI are considerable. AI is already leading to breakthroughs in biology and medicine, and it’s used to control fusion reactors, which could one day provide zero-carbon energy. Generative AI improves productivity, particularly for learners and students.

However, the speed of progress is raising alarm bells. People worry we aren’t prepared to handle powerful AI systems that could be misused or behave in unintended and harmful ways.

In response to such concerns, the world’s governments are attempting regulation. The European Union has approved a draft AI law, the United Kingdom has established an AI safety institute, while US President Joe Biden recently signed an executive order to promote safer development and governance of advanced AI.

Read more:

Who will write the rules for AI? How nations are racing to regulate artificial intelligence

Australians want action to prevent dangerous outcomes from AI

To understand how Australians feel about AI risks and ways to address them, we surveyed a nationally representative sample of 1,141 Australians in January and February 2024.

We found Australians ranked the prevention of “dangerous and catastrophic outcomes from AI” as the number one priority for government action.

Australians are most concerned about AI systems that are unsafe, untrustworthy and misaligned with human values.

Other top worries include AI being used in cyber attacks and autonomous weapons, AI-related unemployment and AI failures causing damage to critical infrastructure.

Strong public support for a new AI regulatory body

Australians expect the government to take decisive action on their behalf. An overwhelming majority (86%) want a new government body dedicated to AI regulation and governance, akin to the Therapeutic Goods Administration for medicines.

Nine in ten Australians also believe the country should play a leading role in international efforts to regulate AI development.

Perhaps most strikingly, two-thirds of Australians would support hitting pause on AI development for six months to allow regulators to catch up.

Government plans should meet public expectations

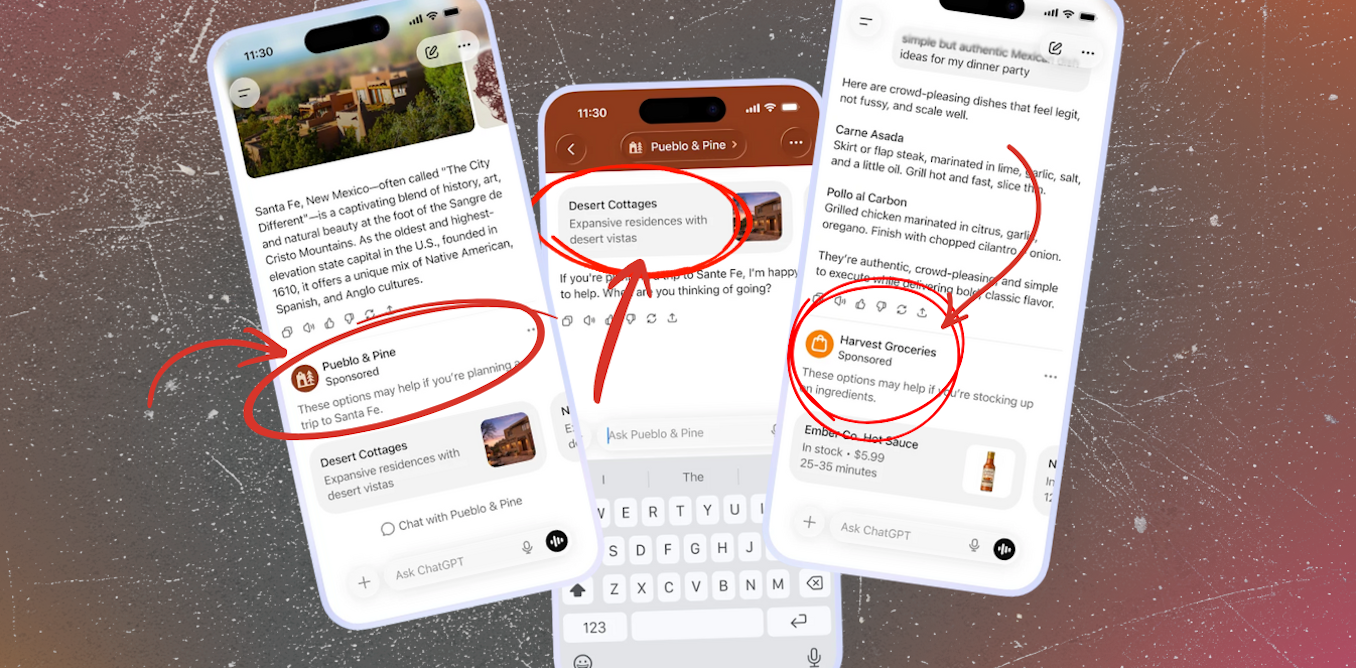

In January 2024, the Australian government published an interim plan for addressing AI risks. It includes strengthening existing laws on privacy, online safety and disinformation. It also acknowledges our currently regulatory frameworks aren’t sufficient.

The interim plan outlines the development of voluntary AI safety standards, voluntary labels on AI materials, and the establishment of an advisory body.

Our survey shows Australians support a more safety-focused, regulation-first approach. This contrasts with the targeted and voluntary approach outlined in the interim plan.

It is challenging to encourage innovation while preventing accidents or misuse. But Australians would prefer the government prioritise preventing dangerous and catastrophic outcomes over “bringing the benefits of AI to everyone”.

-

establishing an AI safety lab with the technical capacity to audit and/or monitor the most advanced AI systems

-

establishing a dedicated AI regulator

-

defining robust standards and guidelines for responsible AI development

-

requiring independent auditing of high-risk AI systems

-

ensuring corporate liability and redress for AI harms

-

increasing public investment in AI safety research

-

actively engaging the public in shaping the future of AI governance.

Figuring out how to effectively govern AI is one of humanity’s great challenges. Australians are keenly aware of the risks of failure, and want our government to address this challenge without delay.

The post “80% of Australians think AI risk is a global priority. The government needs to step up” by Michael Noetel, Senior Lecturer in Psychology, The University of Queensland was published on 03/08/2024 by theconversation.com