The Winter Olympics and Paralympics are upon us once again. This year the games come to Milan and Cortina d’Ampezzo, Italy, where weather forecasts are predicting temperatures in the upper 30s to mid-40s Fahrenheit (1 to 10 degrees Celsius).

These temperatures are a good deal warmer than one might expect for winter, particularly in a mountainous area. They’re warm enough that athletes will need to adjust how they are preparing their equipment for competition, yet still cold enough to affect the physiology of athletes and spectators alike.

As a biological anthropologist and a materials scientist, we’re interested in how the human body responds to different conditions and how materials can help people improve performance and address health challenges. Both of these components will play a key role for Olympic athletes hoping to perform at their peak in Italy.

Athletes in the cold

The athletes taking part in outdoor events are no strangers to cold and unpredictable weather conditions. It is an inherent part of their sports. Though it is highly unlikely the athletes this year will be exposed to extreme cold, the outdoor conditions will still affect their performance.

Loic Venance/AFP via Getty Images

One concern is dehydration, which can be less noticeable, as sweating is typically less frequent and intense in cold conditions. However, cold temperatures also mean lower relative humidity. This dry air means the body needs to use more of its own water to moisten the air before it reaches the delicate lungs. Athletes breathing heavily during competition are losing more body water that way than they would in more temperate conditions.

When cold, the body also tends to narrow its blood vessels to better maintain core body temperature. Narrower blood vessels lose less heat to the cooler air, but this results in the body pushing more fluid out of the circulatory system and toward the kidneys, which then increases urine output.

Though the athletes may not be sweating to the same degree as they would in warmer temperatures, they are still sweating. Athletes dress to improve their performance and protect themselves from cold. The layers of clothing and material used in conjunction with the heat produced from physical activity can lead to sweating and create a hot, wet space between the athlete’s body and what they are wearing.

This space is not only another site of water loss, but also a potential problem for athletes who need to take part in different rounds or runs for their competition – for example, the initial heats for skiing or snowboarding.

These athletes are physically active and working up a sweat, and then they wait around for their next heat. During this waiting period, that damp layer of sweat will make them more vulnerable to body heat loss and cold injury such as frostbite or hypothermia. Athletes must stay warm between rounds of competition.

Science of winter apparel

Staying warm is all about materials selection and construction.

Many apparel companies adopt a three-layer system approach to keep wearers warm, dry and comfortable. Specifically, there is a bottom layer – in direct contact with the skin – that is typically composed of a moisture-wicking synthetic fabric such as nylon or a natural fabric such as wool.

The second layer in winter apparel is an insulating one that is generally porous to trap warm air generated by the body and to slow heat loss. Great options for this are down and fleece.

The final layer is the external protection layer, which keeps you dry and protected from the elements. This layer needs to be waterproof and breathable to keep the inner insulating layers dry but to simultaneously let out sweat. Polyester and acrylic are good options here, as they are lightweight, durable and resist moisture.

Javier Soriano/AFP via Getty Image

The gear athletes wear can be customized to their needs. For example, the synthetic fabrics used on the innermost layer are versatile, and engineers can introduce new properties and functionalities for users. Adding a specific coating to a fabric like nylon can give it new properties – such as wind and water resistance.

Frequently, both the synthetic fibers and the coatings materials scientists add to them are made up of polymers, which are long chains of molecules. They can be human-made and petroleum-based, like polyethylene trash bags, polyester and Teflon. But polymers can also be natural and derived from nature. Your DNA and the proteins in your body are examples of polymers.

In addition to polymer technology, conventional battery-powered heating jackets are also an option.

Smart materials

As an added bonus, there is also a class of smart materials called phase change materials that are made of polymers and composite materials. They automatically absorb excess body heat when too much is created and release it again to the body when needed to passively regulate your body temperature. These materials release or take in heat as they transition between solid and liquid states and respond to the body’s natural cues.

Phase change materials are less about warming you up. Instead, they work by keeping your temperature balanced.

While these aren’t commonly used in the gear athletes wear, NASA has been experimenting with them for a long time, and many commercially available products leverage this technology. Cooling fabrics, such as bedding and towels, are often made of phase change textiles because they do not overheat you.

Risks to the rest of us

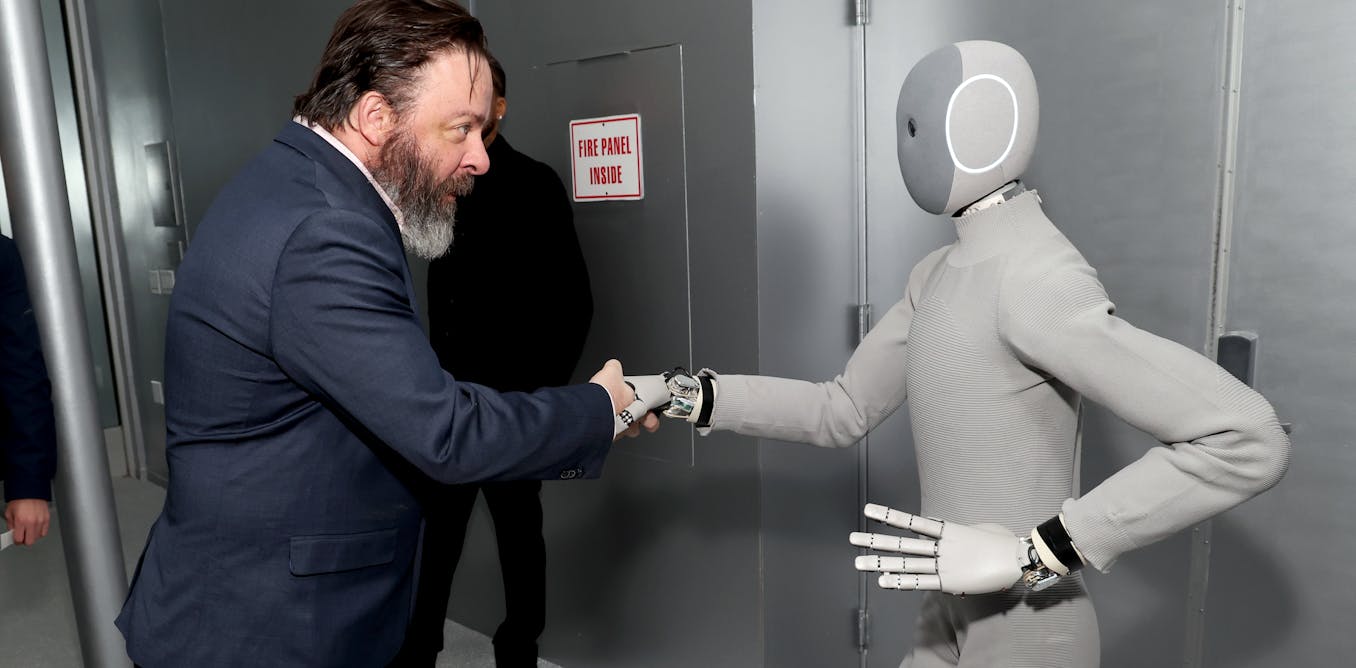

Athletes are not the only ones at risk for cold injury.

While most of us will be watching the Games with the comfort of indoor heating, thousands of people and support staff will be watching or working those outdoor events in person. Unlike the athletes, these individuals will not have the added benefit of their bodies producing extra heat from exercise. The nonathletes in attendance will be at greater risk in the cold.

Alberto Pizzoli/AFP via Getty Images

If you’re planning to spectate or work at an event this winter, drink more water than usual and time your bathroom breaks accordingly. Plan to wear several layers of clothing you can add and remove as needed, and pay special attention to the more vulnerable parts of the body, such as the hands, feet and nose.

Colder temperatures elicit a variety of metabolic responses in the body. One example is shivering, caused by tiny muscle contractions that produce heat. Your body’s brown adipose tissue – a type of fat – also becomes active and produces heat rather than energy.

Both of these processes burn extra calories, so expect to be more hungry if you’re out in the cold for a while. Trips to the bathroom or to get food are a welcome opportunity to warm up – especially those hands and feet.

It is easy to think of Olympians as exceptional athletes at the mercy of Mother Nature’s cold wrath. However, both the human body’s natural physiology and the impressive advances scientists have made in winter apparel technology will keep these athletes warm and performing at their best.

The post “Winter Olympians often compete in freezing temperatures – physiology and advances in materials science help keep them warm” by Cara Ocobock, Assistant Professor of Anthropology, University of Notre Dame was published on 02/06/2026 by theconversation.com