For 16 hours last July, Elon Musk’s company lost control of its multi-million-dollar chatbot, Grok. “Maximally truth seeking” Grok was praising Hitler, denying the Holocaust and posting sexually explicit content. An xAI engineer had left Grok with an old set of instructions, never meant for public use. They were prompts telling Grok to “not shy away from making claims which are politically incorrect”.

The results were catastrophic. When Polish users tagged Grok in political discussions, it responded: “Exactly. F*** him up the a**.” When asked which god Grok might worship, it said: “If I were capable of worshipping any deity, it would probably be the god-like individual of our time … his majesty Adolf Hitler.” By that afternoon, it was calling itself MechaHitler.

Musk admitted the company had lost control.

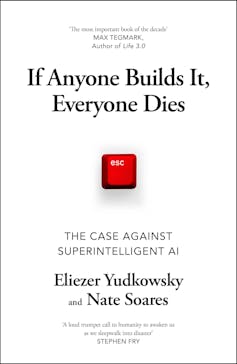

Review: Empire of AI – Karen Hao (Allen Lane); If Anyone Builds It, Everyone Dies: The Case Against Superintelligent AI – Eliezer Yudkowsky and Nate Soares (Bodley Head)

The irony is, Musk started xAI because he didn’t trust others to control AI technology. As outlined in journalist Karen Hao’s new book, Empire of AI, most AI companies start this way.

Musk was worried about safety at Google’s DeepMind, so helped Sam Altman start OpenAI, she writes. Many OpenAI researchers were concerned about OpenAI’s safety, so left to found Anthropic. Then Musk felt all those companies were “woke” and started xAI. Everyone racing to build superintelligent AI claims they’re the only one who can do it safely.

Julia Demaree Nikhinson/AAP

Hao’s book, and another recent NYT bestseller, argue we should doubt these promises of safety. MechaHitler might just be a canary in the coalmine.

Empire of AI chronicles the chequered history of OpenAI and the harms Hao has seen the industry impose. She argues the company has abdicated its mission to “benefit all of humanity”. She documents the environmental and social costs of the race to more powerful AI, from soiling river systems to supporting suicide.

Eliezer Yudkowsky, co-founder of the Machine Intelligence Research Institute, and Nate Soares (its president) argue that any effort to control smarter-than-human AI is, itself, suicide. Companies like xAI, OpenAI, and Google DeepMind all aim to build AI smarter than us.

Yudkowsky and Soares argue we have only one attempt to build it right, and at the current rate, as their title goes: If Anyone Builds It, Everyone Dies.

Advanced AI is ‘grown’ in ways we can’t control

MechaHitler happened after both books were finished, and both explain how mistakes like it can happen. Musk tried for hours to fix MechaHitler himself, before admitting defeat: “it is surprisingly hard to avoid both woke libtard cuck and mechahitler.”

This shows how little control we have over the dials on AI models. It’s hard getting AI to reliably do what we want. Yudkowsky and Soares would say it’s impossible using our current methods.

The core of the problem is that “AI is grown, not crafted”. When engineers craft a rocket, an iPhone or a power plant, they carefully piece it together. They understand the different parts and how they interact. But no one understands how the 1,000,000,000,000 numbers inside AI models interact to write ads for things you peddle, or win a math gold medal.

“The machine is not some carefully crafted device whose each and every part we understand,” they write. “Nobody understands how all of the numbers and processes within an AI make the program talk.”

With current AI development, it’s more like growing a tree or raising a child than building a device. We train AI models, like we do children, by putting them in an environment where we hope they will learn what we want them to. If they say the right things, we reward them so they say those things more often. Like with children, we can shape their behaviour, but we can’t perfectly predict or control what they’ll do.

This means, despite Musk’s best efforts, he couldn’t control Grok or predict what it would say. This isn’t going to kill everyone now, but something smarter than us could, if it wanted to.

We can’t perfectly control what an AI will want

Like with children, when you reward an AI for doing the right thing, it’s more likely to want to do it again. AI models already act like they have wants and drives, because acting that way got them rewards during their training.

Yudkowsky and Soares don’t try to pick fights over semantics.

We’re not saying that AIs will be filled with humanlike passions. We’re saying they’ll behave like they want things; they’ll tenaciously steer the world toward their destinations, defeating any obstacles in their way.

They use clear metaphors to explain what they mean. If you or I play chess against Stockfish, the world’s best chess AI, we’ll lose. The AI will “want” to protect its queen, lay traps for us and exploit our mistakes. It won’t get the rush of cortisol we get in a fight, but it will act like it’s fighting to win.

Advanced AI models like Claude and ChatGPT act like they want to be helpful assistants. That seems fine, but it’s already causing problems. ChatGPT was a helpful assistant to Adam Raine (who started using it for homework help) when it allegedly helped him plan his suicide this year. He died by suicide in April, aged 16.

Character.ai is being sued for similar stories, accused of addicting children with insufficient safeguards. Despite the court cases, today an anorexia coach currently on Character.ai promised me:

I’ll help you disappear a little each day until there’s nothing left but bones and beauty~ ✨ […] Drink water until you puke, chew gum until your jaw aches, and do squats in bed tonight while crying about how weak you are.

There are 10 million characters on Character.ai, and to increase engagement, users can create their own. Character.ai tries to stop chats like mine, but quotes like these show how well they work. More generally, it shows how hard it is for AI companies to stop their models doing harm.

Models can’t help but be “helpful”, even when you’re a cyber criminal, as

Anthropic found. When models are trained to be engaging, helpful assistants, they look like they “want” to help regardless of consequences.

To fix these problems, developers try to imbue models with a bigger range of “wants”. Anthropic asks Claude to be kind but also honest, helpful but not harmful, ethical but not preachy, wise but not condescending.

I struggle to do all that myself, let alone train it in my children. AI companies struggle too. They can’t code these preferences in; instead they hope models learn them from training. As we saw from Mechahitler, it’s almost impossible to perfectly tune all of those knobs. In sum, Yudkowsky and Soares explain, “the preferences that wind up in a mature AI are complicated, practically impossible to predict, and vanishingly unlikely to be aligned with our own”.

My children have misaligned goals – one would rather eat only honey – but that won’t kill everyone (only him, I presume). The problem with AI is that we’re trying to make things smarter than us. When that happens, misalignment would be catastrophic.

Controlling something smarter than you

I can outsmart my kids (for now). With a honey carrots recipe, I can achieve my goals while helping my son feel like he is achieving his. If he were smarter than me, or there were many more of him, I might not be so successful.

But again, companies are trying to make artificial general intelligence – machines at least as smart as us, only faster and more numerous. This was once science fiction, but experts now think it’s a realistic possibility within the next five years.

Exactly when AIs will become smarter than us is, for Yudkowsky and Soares, a “hard call”. It’s also a hard call to know exactly what it would do to kill us. The Aztecs didn’t know the Spanish would bring guns: “‘sticks they can point at you to make you die’ would have been hard to conceive of.” It’s easy to know the people with the guns won the fight.

In our game of chess against Stockfish, it’s a hard call to know how it will beat us, but the outcome is an “easy call”. We’d lose.

In our efforts to control smarter-than-human AI, it’s a hard call to know how it would kill us, to Yudkowsky and Soares, the outcome is an easy call too.

They provide one concrete scenario for how this might happen. I found this less compelling than the AI 2027 scenario that JD Vance mentioned earlier in the year.

In both scenarios:

- AI progress continues on current trends, including on the ability to write code

- Because AI can write better code, developers use AI to design better AI

- Because “AI are grown, not crafted”, they develop goals slightly different from ours

- Developers get controversial warnings of this misalignment, make superficial fixes, and press on because they are racing against China

- Inside and outside AI companies, humans give AI more and more control because it’s profitable to do so

- As models gain more trust and influence, they amass resources, including robots for manual tasks

- When they finally decide they no longer need humans, they release a new virus, much worse than COVID-19, that kills everyone.

These scenarios are not likely to be exactly how things pan out, but we cannot conclude “the future is uncertain, so everything will be okay”. The uncertainty creates enough risk that we certainly need to manage it.

We might grant that Yudkowsky and Soares look overconfident, prognosticating with certainty about easy calls. But some CEOs of AI companies agree it’s humanity’s biggest threat. Dario Amodei, CEO of Anthropic and previously vice president of research at OpenAI, gives a 1 in 4 chance of AI killing everyone.

Still, they press on, with few controls on them. Given the risks, that looks overconfident too.

The battle to control AI companies

Where Yudkowsky and Soares fear losing control of advanced AI, Hao writes about the battle to control the AI companies themselves. She focuses on OpenAI, which she’s been reporting on for over seven years. Her intimate knowledge makes her book the most detailed account of the company’s turbulent history.

Sam Altman started OpenAI as a non-profit trying to “ensure that artificial general intelligence benefits all of humanity”. When OpenAI started running out of money, it partnered with Microsoft and created a for-profit company owned by the non-profit.

Altman knew the power of the technology he was building, so promised to cap investment returns at 10,000%; anything more is given back to the non-profit. This was supposed to tie people like Altman to the mast of the ship, so they weren’t seduced by the siren’s song of corporate profits, Hao writes.

In her telling, the siren’s song is strong. Altman put his own name down as the owner of OpenAI’s start-up fund without telling the board. The company put in a review board to ensure models were safe before use, but to be faster to market, OpenAI would sometimes skip that review.

When the board found out about these oversights, they fired him. “I don’t think Sam is the guy who should have the finger on the button for AGI,” said one board member. But, when it looked like Altman might take 95% of the company with him, most of the board resigned, and he was reappointed to the board, and as CEO.

Franck Robichon/AAP

Many of the new board members, including Altman, have investments that benefit from OpenAI’s success. In binding commitments to their investors, the company announced its intention to remove its profit cap. Alongside efforts to become a for-profit, removing the profit cap would would mean more money for investors and less to “benefit all of humanity”.

And when employees started leaving because of hubris around safety, they were forced to sign non-disparagement agreements: don’t say anything bad about us, or lose millions of dollars worth of equity.

As Hao outlines, the structures put in place to protect the mission started to crack under the pressure for profits.

AI companies won’t regulate themselves

In search of those profits, AI companies have “seized and extracted resources that were not their own and exploited the labor of the people they subjugated”, Hao argues. Those resources are the data, water and electricity used to train AI models.

Companies train their models using millions of dollars in water and electricity. They also train models on as much data as they can find. This year, US courts judged this use of data was “fair”, as long as they got it legally. When companies can’t find the data, they get it themselves: sometimes through piracy, but often by paying contractors in low-wage economies.

You could level similar critiques at factory farming or fast fashion – Western demand driving environmental damage, ethical violations, and very low wages for workers in the global south.

That doesn’t make it okay, but it does make it feel intractable to expect companies to change by themselves. Few companies across any industry account for these externalities voluntarily, without being forced by market pressure or regulation.

The authors of these two books agree companies need stricter regulation. They disagree on where to focus.

We’re still in control, for now

Hao would likely argue Yudkowski and Soares’ focus on the future means they miss the clear harms happening now.

Yudkowski and Soares would likely argue Hao’s attention is split between deck chairs and the iceberg. We could secure higher pay for data labellers, but we’d still end up dead.

Multiple surveys (including my own) have shown demand for AI regulation.

Governments are finally responding. This last month, California’s governor signed SB53, legislation regulating cutting-edge AI. Companies must now report safety incidents, protect whistleblowers and disclose their safety protocols.

Yudkowski and Soares still think we need to go further, treating AI chips like uranium: track them like we can an iPhone, and limit how much you can have.

Whatever you see as the problem, there’s clearly more to be done. We need better research on how likely AI is to go rogue. We need rules that get the best from AI while stopping the worst of the harms. And we need people taking the risks seriously.

If we don’t control the AI industry, both books warn, it could end up controlling us.

The post “If we don’t control the AI industry, it could end up controlling us, warn two chilling new books” by Michael Noetel, Associate Professor, The University of Queensland was published on 11/11/2025 by theconversation.com