It feels like everything is slowly but surely being affected by the rise of artificial intelligence (AI). And like every other disruptive technology before it, AI is having both positive and negative outcomes for society.

One of these negative outcomes is the very specific, yet very real cultural harm posed to Australia’s Indigenous populations.

The National Indigenous Times reports Adobe has come under fire for hosting AI-generated stock images that claim to depict “Indigenous Australians”, but don’t resemble Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

Some of the figures in these generated images also have random body markings that are culturally meaningless. Critics who spoke to the outlet, including Indigenous artists and human rights advocates, point out these inaccuracies disregard the significance of traditional body markings to various First Nations cultures.

Adobe’s stock platform was also found to host AI-generated “Aboriginal artwork”, raising concerns over whether genuine Indigenous artworks were used to train the software without artists’ consent.

The findings paint an alarming picture of how representations of Indigenous cultures can suffer as a result of AI.

How AI image generators work

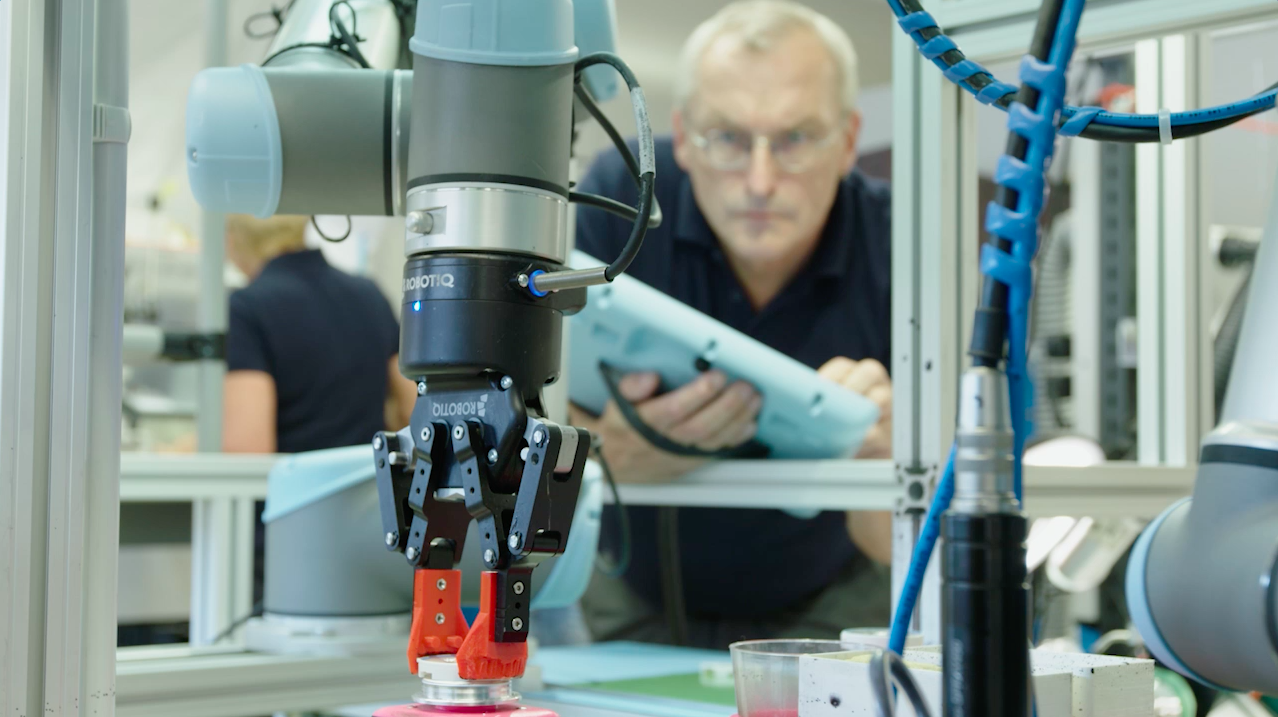

While training AI image generators is a complex affair, in a nutshell it involves feeding a neural network millions of images with associated text descriptions.

This is much like how you would have been taught to recognise various objects as a small child: you see a car and you’re told it’s a “car”. Then you see a different car, and are told it is also a “car”. Over time you begin to discern patterns that help you differentiate between cars and other objects.

You gain an idea of what a car “is”. Then, when asked to draw a picture of a car, you can synthesise all your knowledge to do so.

Many AI image generators produce images through what is called “reverse diffusion”. In essence, they take the images they’ve been trained on and add “noise” to them until they are just a mix of pixels of random colour and brightness. They then continually decrease the amount of noise, until the correct image is displayed.

Author provided (no reuse)

The process of creating an AI image begins with a text prompt by the user. The image generator then compares how the words in the prompt associate with its learning, and produces an image that satisfies the prompt. This image will be original, in that it won’t exist anywhere else.

If you’ve gone through this process, you’ll appreciate how difficult it can be to control the image that is produced.

Say you want your subject to be wearing a very specific style of jacket; you can prompt it as precisely as you like – but you may never get it perfect. The result will come down to how the model was trained and the dataset it was trained on.

We’ve seen early versions of the AI image generator Midjourney respond to prompts for “Indigenous Australians” with what appeared to be images of African tribespeople: essentially an amalgam of the “noble savage”.

Cultural flattening through AI

Now, consider that in the future, millions of people will be generating AI images from various generators. These may be used for teaching, promotional materials, advertisements, travel brochures, news articles and so on. Often, there will be little consequence if the images generated are “generic” in appearance.

But what if it was important for the image to accurately reflect what the creator was trying to represent?

In Australia, there are more than 250 Indigenous languages, each one specific to a particular place and people. For each of these groups, language is central to their identity, sense of belonging and empowerment.

It is a core element of their culture – just as much as their connection to a specific area of land, their kinship systems, spiritual beliefs, traditional stories, art, music, dance, laws, food practices and more.

But when an AI model is trained on images of Australian Indigenous peoples’ art, clothing, or artefacts, it isn’t also necessarily fed detailed information of which language group each image is associated with.

The result is “cultural flattening” through technology, wherein culture is made to appear more uniform and less diverse. In one example, we observed an AI image generator produce an image of what was mean to be an elderly First Nations man in a traditional Papuan headdress.

This is an example of technological colonialism, wherein tech corporations contribute to the homogenisation and/or misrepresentation of diverse Indigenous cultures.

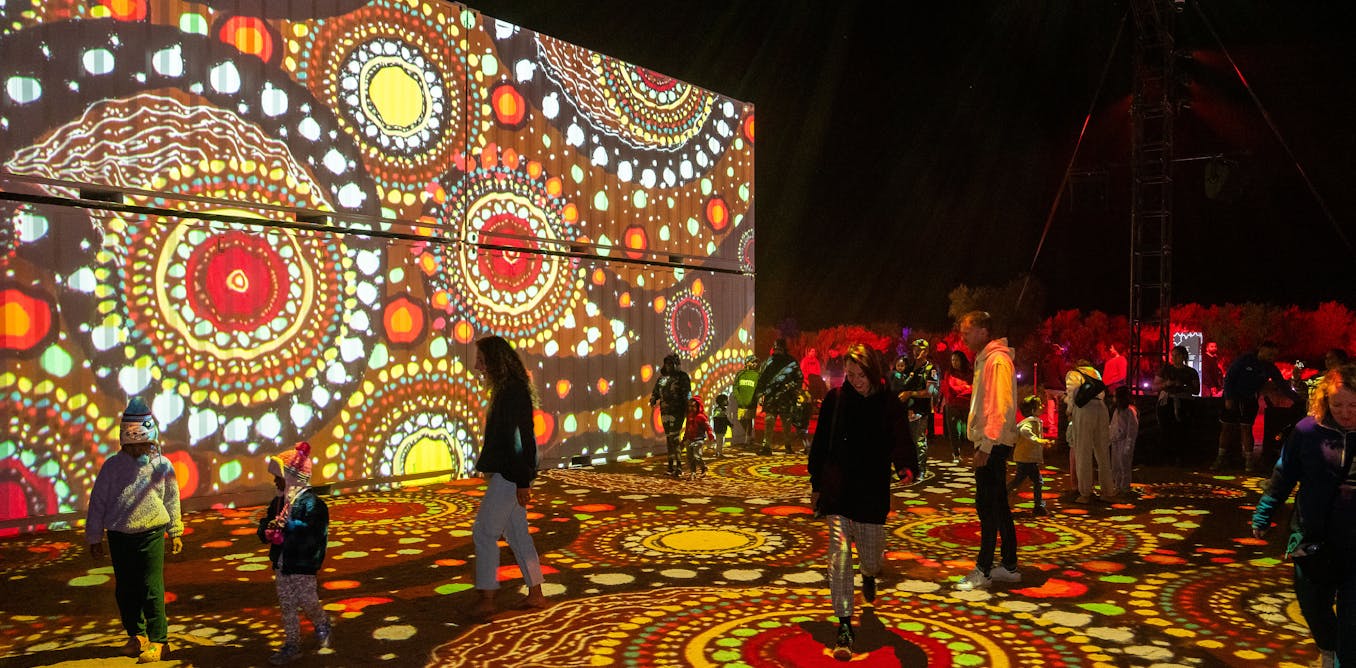

We’ve also seen pictures of “Indigenous art” on stock footage websites that are clearly labelled as being produced by AI. How can these be sold as images of First Nations art if no First Nations person was involved in making them? Any connection to deep cultural knowledge and lived experience is completely absent.

Liz Hobday/AP

Besides the obvious economic consequences for artists, long-term technological misrepresentation could also have adverse impacts on the self-perception of Indigenous individuals.

What can be done?

While there’s currently no simple solution, progress begins with discussion and engagement between AI companies, researchers, governments and Indigenous communities.

These collaborations should result in strategies for reclaiming visual narrative sovereignty. They may, for instance, implement ethical guidelines for AI image generation, or reconfigure AI training datasets to add nuance and specificity to Indigenous imagery.

At the same time, we’ll need to educate AI users about the risk of cultural flattening, and how to avoid it when representing Indigenous people, places, or art. This would require a coordinated approach involving educational institutions from kindergarten upwards, as well as the platforms that support AI image creation.

The future goal is, of course, the respectful representation of Indigenous cultures that are already fighting for survival in many other ways.

The post “How AI images are ‘flattening’ Indigenous cultures – creating a new form of tech colonialism” by John McMullan, Screen Production Lecturer, Murdoch University was published on 03/12/2025 by theconversation.com