At this year’s Winter Olympics in Italy, the controversy began with a fingertip.

A disputed double-touch—whether a curler had brushed a moving stone twice—sparked protests, profanity-laced exchanges, and heated debate about sportsmanship. In a game that prides itself on mutual trust and the idea of competition as a shared test of skill, even the suggestion of impropriety can ripple far beyond a single end.

But if a double-touch can shake the sport, what happens when the controversy isn’t about a fingertip, but an algorithm?

That’s the question shadowing the rise of analytics driven by machine learning and a new breed of AI-powered robots that can throw stones, read the ice, and calculate strategy with machine precision.

Some of these robots, such a “Curly,” have already toppled elite human opponents in head-to-head competitions. Others, engineered either to replicate the biomechanics of human shot delivery or to fire stones consistently with repeatable speed and rotation, are transforming the sport by dissecting technique and strategy with a level of rigor no coach with a stopwatch could match.

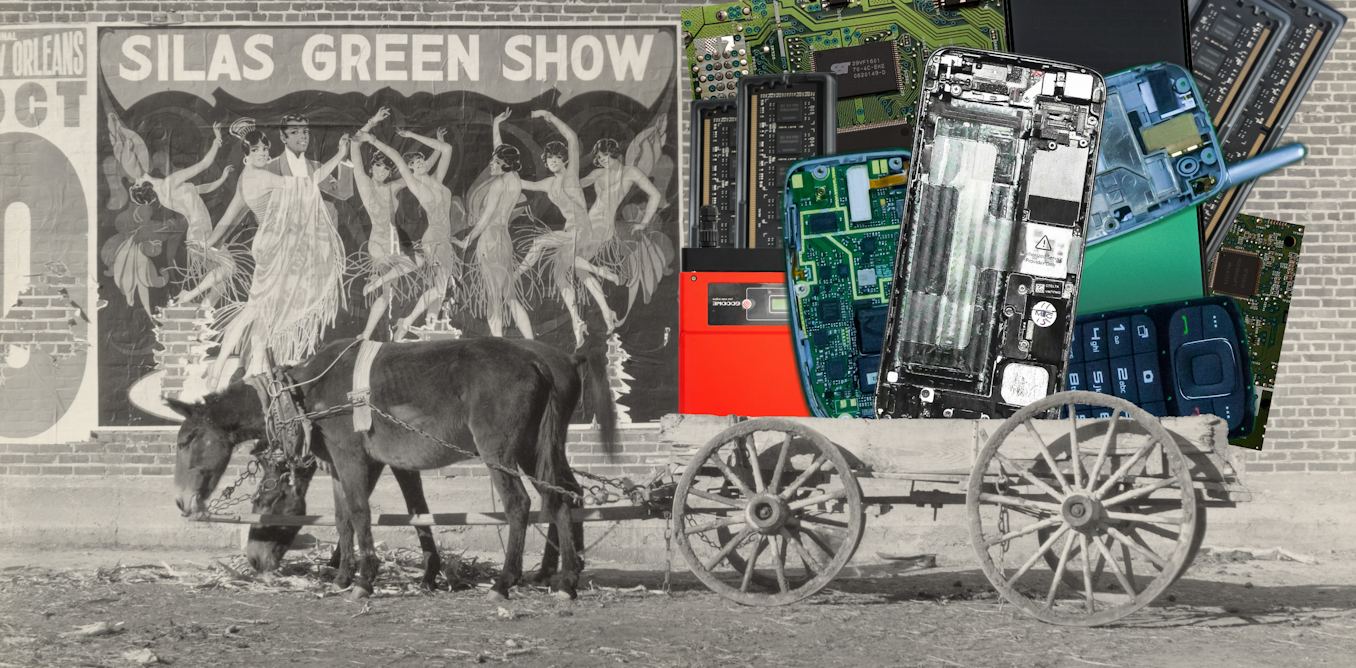

Seen here in action, the two-part robot system named Curly made its debut in 2018 ahead of that year’s Paralympic Winter Games in Pyeongchang.TUBerlinTV/YouTube

“The amount of innovation I’m seeing is just tremendous,” says Glenn Paulley, a retired computer scientist who now runs Throwing Rocks Consulting Services, where he coaches curlers and advises teams on analytics.

Fueled by investments from governments and sporting bodies around the world, the pursuit of a competitive edge has escalated into a data-driven push for marginal gains ahead of each Olympic cycle. “They’re trying like crazy to elevate their national team programs,” Paulley says, “and they’re doing it in every way possible.” By the time medals are handed out in Cortina d’Ampezzo this weekend, the imprint of this full-throttle tech offensive could be etched into every sheet of ice.

Yet, as algorithms begin suggesting shots, the contours of fair play blur. Regulators and coaches alike are grappling with where to draw the line. And as top curlers lean more into AI and robotic systems, some fear the loss of something fundamental: the quiet, hard-earned feel for ice that separates veterans from novices.

“It’s a big debate!” says Emily Zacharias, a former elite curler from Manitoba who captured gold representing Canada at the 2020 World Junior Curling Championships.

Three decades ago, Garry Kasparov sat across from IBM’s Deep Blue and discovered that even the most cerebral of games could be unsettled by silicon. Curling, long called “chess on ice,” may now be entering its own version of that reckoning.

Can New Tech Comply With the “Spirit of Curling”?

Curling has been at this kind of crossroads before. A decade back, the sweeping-fabric controversy known as “Broomgate” triggered accusations of technological doping, a dispute that tore at the heart the sport’s ethos of trust and bonhomie.

The World Curling Federation responded by clamping down on brush materials, but AI now poses a broader challenge. It is not just a better broom, but a decision engine, capable of shifting authority from a player’s judgment in the “house” to a model running in the cloud.

The six-legged “hexapod” curling robot was displayed at the World Robot Conference 2022 in Beijing, where that year’s Olympic Games were also held.Anna Ratkoglo/Sputnik/AP

The six-legged “hexapod” curling robot was displayed at the World Robot Conference 2022 in Beijing, where that year’s Olympic Games were also held.Anna Ratkoglo/Sputnik/AP

It’s a prospect that unsettles some athletes and ethicists, who worry about what gets lost as optimization tightens its grip on a sport long governed by the so-called Spirit of Curling, an unwritten code of integrity, fairness, and respect.

“We’re at a point now where just about everything that we used to hold up as uniquely human is now being eroded by technology—and we feel a loss,” says Jason Millar, who runs the Canadian Robotics and AI Ethical Design Lab at the University of Ottawa.

“The AI doesn’t care,” he adds. “There’s no ‘Spirit’ there.”

Building Rock-Solid Curling Robots

The Curly robot first made waves in 2018 when, ahead of that year’s Paralympic Winter Games in Pyeongchang, engineers at Korea University in Seoul unveiled the AI-powered device—or, rather, two coordinated devices, a pair of “skip” and “thrower” units, designed to read the ice and deliver stones.

Driven by a physics-based simulator and an adaptive deep reinforcement-learning framework, the robot didn’t simply replay pre-programmed shots. It learned from its own misses, updated its aim based on the distance gaps between intended and actual stone positions, and factored in the cumulative wear of pebbled ice as a match unfolded.

That capacity was put to the test in a series of mini-games against top-ranked Korean athletes. As reported in the journal Science Robotics, Curly started slow, dropping the opening match as it calibrated to the live ice. But it then went on to win the next three contests, demonstrating what its creators called “human-level performance” under real-world conditions.

The next Winter Olympics—the Beijing 2022 Games—then brought a more agile machine: a “hexapod” curling robot built to walk, align, and throw like a human curler.

With six legs, the hexapod robot can act more like a human curler when launching the stone, putting a new spin on curling robot tech.FlyingDumplings/YouTube

With its six-legged gait for stable traction and flexibility on the ice, the robot could pivot at the “hack,” the rubber foothold curlers use to launch their delivery. From there, the hexapod set its angle, kicked off, and glided on a skateboard-like undercarriage before releasing the stone, imparting competition-level spin.

Equipped with LiDAR and cameras, the robot scanned the sheet to map stone positions and fed those data into software that calculated collision paths and solved for the precise release parameters needed to execute a chosen strategy.

Curling Bots Leave Broom for Improvement

For all the technical prowess of Curly and the hexapod, one stubborn constraint remains: No robot can sweep—at least not yet.

There are no Roomba-like machines flanking the stone, frantically brushing to extend its travel or hold its line. Once released, the robot’s shot is fate, untouched by the vigorous, broom-flailing choreography that so often determines whether a stone bites the button or drifts wide.

“These robots are leaving out a huge chunk of potential that humans are bringing to the game,” says Steven Passmore, a human-movement scientist at the University of Manitoba in Winnipeg who, together with Zacharias, co-authored a comprehensive review of the scientific literature on curling.

At the time of their data cut-off, in 2021, they found nearly two dozen published studies about robotics, AI, and emerging tech in the sport. But as Zacharias points out, the most sophisticated tools shaping elite play often never appear in academic journals, developed behind closed doors and closely guarded as competitive secrets.

For her part, Zacharias—who competed at four Canadian women’s curling championships between 2021 and 2024—says she never once practiced against a robot. But she has trained with a rock launcher: a mechanized delivery system that fires stones at precisely calibrated speeds and rotations, over and over.

By standardizing the throw, the device allows athletes to isolate how different sweeping techniques, brush-head fabrics, or ice temperatures alter a stone’s path, explains Paulley. “It means you can run repeated experiments in order to test the impact of different variables,” he says. “And in curling, there are a lot of variables.”

Cutting-Edge Tech Helps Athletes Train

In Japan, all these technologies and more are being explored in a government-backed initiative called Curling of the Future.

The program brings together university engineers, sporting agencies, and elite athletes to prototype delivery robots and sweep-assist machines, along with AI strategy engines, instrumented “smart stones,” and rock-launcher systems for controlled training.

“The core objective is elite performance: improving decision-making and the quality of training so that Japan can strengthen its competitiveness in international competition,” says Yoshinari Takegawa, an information scientist at the Future University Hakodate who is co-leading the project.

Dylan Rusnak, a kinesiology student at Red Deer Polytechnic, contributed to the project developing a VR system for curling. Rusnak wears a Meta Quest headset (left) while demoing the system, which shows athletes immersive views of the rink (right). Red Deer Polytechnic

Dylan Rusnak, a kinesiology student at Red Deer Polytechnic, contributed to the project developing a VR system for curling. Rusnak wears a Meta Quest headset (left) while demoing the system, which shows athletes immersive views of the rink (right). Red Deer Polytechnic

The technology push isn’t confined to Olympic play either. At the Paralympics next month, the Canadian national wheelchair curling squad will be coming primed with training sessions inside a full virtual replica of the Cortina Curling Olympic Stadium, courtesy of a VR system developed by mechanical engineer Jennifer Dornstauder and her students at Red Deer Polytechnic in Alberta.

The setup drops athletes into an immersive curling rink via a Meta Quest headset, where they can look down and see virtual renderings of their legs, wheelchair, throwing stick, stones and the ice surface beneath them.

According to Mick Lizmore, head coach of Canada’s National Wheelchair Curling Program, his team has used the VR to help visualize the venue where they will be competing and for group tactical training, even when they can’t meet together in person. Beyond sharpening elite preparation, Dornstauder says, the same tool should help expand access to wheelchair curling for people with disabilities who face mobility challenges or limited ice availability.

“VR is just this amazing tool that is almost designed for getting around these barriers,” she says.

Will Tech Change Curling?

Many of the technologies entering curling are, in many ways, benign—tools for analysis, accessibility, and incremental refinement rather than wholesale disruption. A rock launcher standardizes practice. A VR headset extends rehearsal beyond the rink. A strategy engine offers probabilities, not ultimatums.

Taken together, however, they reveal how thoroughly digital systems are seeping into every layer of the sport.

AI-powered sparring machines tuned to mimic a rival team’s tendencies, and thus capable of playing out fully simulated preparatory matches, remain a fantasy. National curling programs operate on tight budgets, limiting how far and how fast innovation can go. And even well-funded federations must balance software and robotics against coaching, travel, and ice time.

Rock launchers provide a consistent throw to help athletes practice sweeping.Sean Maw/University of Saskatchewan

Rock launchers provide a consistent throw to help athletes practice sweeping.Sean Maw/University of Saskatchewan

Yet as money continues to flow into high-performance curling, those possibilities draw closer.

“It’s probably just a matter of time,” says Sean Maw, a sports engineer at the University of Saskatchewan who has built rock launchers and studies the complexities of curling.

For now, the stones still leave human hands—hands capable of brilliance, instinct, and the occasional double-touch—and the final call still rests with the skip in the house. But the algorithms are edging closer to the button.

The post “Tech Is Taking Over Olympic Curling” by Elie Dolgin was published on 02/18/2026 by spectrum.ieee.org

.jpg)