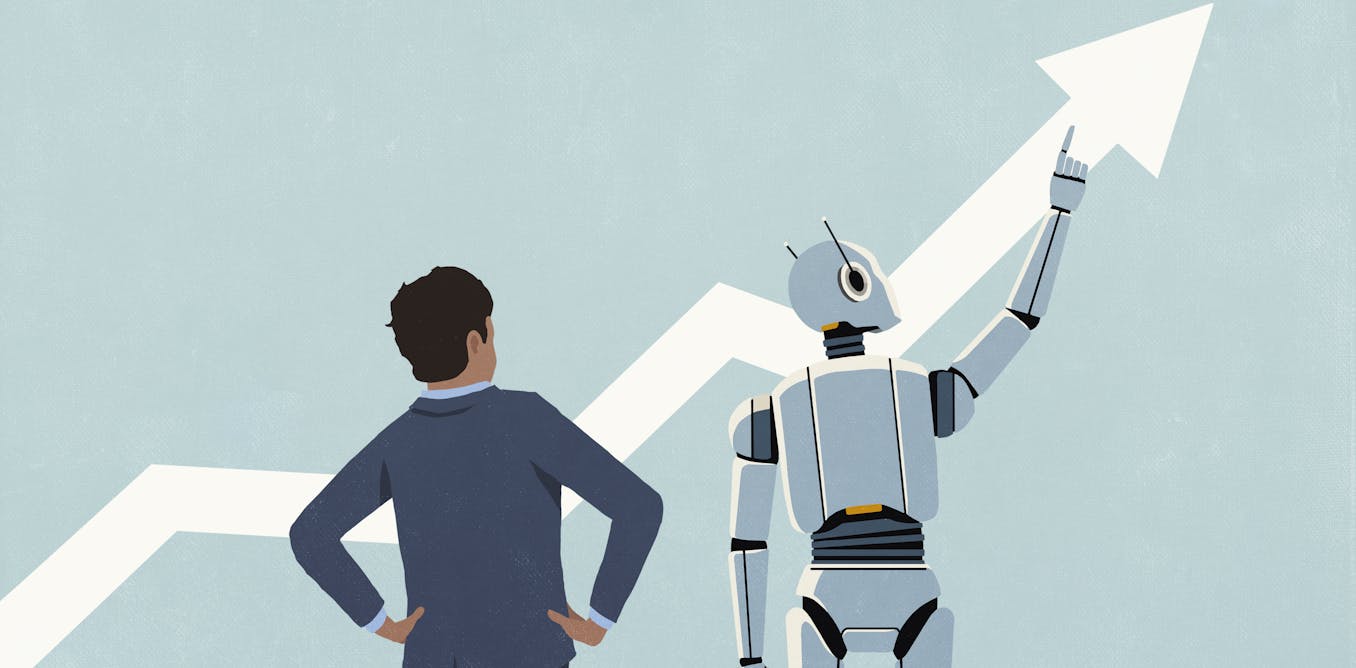

The retirement of West Midlands police chief Craig Guildford is a wake-up call for those of us using artificial intelligence (AI) tools at work and in our personal lives. Guildford lost the confidence of the home secretary after it was revealed that the force used incorrect AI-generated evidence in their controversial decision to ban Israeli football fans from attending a match.

This is a particularly egregious example, but many people may be falling victim to the same phenomenon – outsourcing the “struggle” of thinking to AI.

As an expert on how new technology reshapes society and the human experience, I have observed a growing phenomenon which I and other researchers refer to as “cognitive atrophy”.

Essentially, AI is replacing tasks many people have grown reluctant to do themselves – thinking, writing, creating, analysing. But when we don’t use these skills, they can decline.

We also risk getting things very, very wrong. Generative AI works by predicting likely words from patterns trained on vast amounts of data. When you ask it to write an email or give advice, its responses sound logical. But it does not understand or know what is true.

There are countless anecdotal examples of people feeling like AI use is making them “lazy” or “stupid”. A recent study found that generative AI use among university students is driven by higher workloads and time pressure, and that greater AI use is associated with increased procrastination and memory loss and poorer academic performance. Misuse of generative AI tools (for example, to cheat on exams) may undermine skills like critical thinking, creativity and ethical decision-making.

Recognising atrophy

You might observe this happening in your own life. One sign might be that you’ve moved away from creating an initial unpolished version of a task. Not so long ago, you might have started with a rough draft – a messy, human brainstorming process on a whiteboard, a notepad or the back of a napkin.

You may now feel more comfortable with the “prompt-and-accept” reflex: asking for and accepting solutions, rather than trying to tease out your own ideas and solve problems.

If your first instinct for every task is to ask an AI tool to give you a starting point, you are skipping the most vital part of thinking. This is the heavy lifting of structure, logic and sparking new ideas which excite us.

Another sign of atrophy is a shrinking of your frustration threshold. If you find that after only 60 seconds of mental effort you feel an itch to see what AI suggests, your stamina for ambiguity, a little self-doubt and frustration is probably compromised. Impatience cuts off the cognitive space needed for divergent thinking – the ability to generate multiple unique solutions.

Do you find yourself accepting AI-generated output without questioning its validity? Or do you find yourself unable to trust your own gut instinct without checking with an AI search? This may be a sign that you are shifting from being a decision-maker to a decision-approver or worse, a passive passenger of your own thinking process.

Reclaim your thinking

How can you combat this cognitive atrophy? The goal should not necessarily be to quit using AI entirely, but to move toward responsible autonomy – reclaiming your capacity to think and make decisions for yourself, rather than blindly outsourcing judgement to AI systems. This requires building some strategic friction back into your daily life. It means embracing uncertainty and learning from the process of thinking, even if you are wrong on occasion. Here are some practical things you can try:

1. The 30-minute rule

Before you open any AI interface, try to commit to 30 minutes of deep thinking. Use a pen and paper. Pick your topic or task, and map out the problem, the potential solutions, the risks and the stakeholders. For example, before asking an AI tool to draft a marketing strategy, map out your target audience. Try to identify potential ethical or reputational risks and sketch out some ideas.

By doing the initial cognitive work, you will likely feel a stronger sense of ownership for your output. If you eventually use AI, use it to refine your thoughts, not replace them.

NewAfrica/Shutterstock

2. Be sceptical

One of the most persistent concerns is that people use AI as an oracle and believe its output without question. Instead, treat it as a deeply unreliable colleague who may know the right answer, but hallucinates from time to time.

Task yourself with finding three specific errors with AI’s output, or to break its logic. Tell yourself that you can do better. This forces your brain out of the consumer mode and back into creator and editor mode, keeping your critical faculties sharp.

3. Create thinking spaces

Identify one core task in your personal or professional life that you enjoy doing, and commit to performing it entirely without AI assistance. These thinking spaces help your brain maintain its ability to navigate complex and open-ended challenges from scratch.

As you regain confidence, try branching out to other tasks. If you lead a team at work, allow people to have time to think slowly in this way, free from the pressure of producing more.

4. Measure your ‘return on habit’

Think about the “return on habit” – the long-term benefits such as improved health or happiness gained from consistently practising small positive routines. Ask yourself: Is this AI tool making me smarter, or just faster? Is faster better? For whom?

If a tool helps you notice things you did not see before, it may enhance your thinking, not replace it. However, if it is merely replacing a skill you used to possess and did well, it is an atrophying agent. If you are not gaining a new capability in exchange for the one you have outsourced, you may be conceding to the algorithms.

The post “Is AI hurting your ability to think? How to reclaim your brain” by Noel Carroll, Associate Professor in Business Information Systems, University of Galway was published on 01/22/2026 by theconversation.com

.jpg)