In the sweltering summer of AD18, a desperate chant echoed across China’s sun-scorched plains: “Heaven has gone blind!” Thousands of starving farmers, their faces smeared with ox blood, marched toward the opulent vaults held by the Han dynasty’s elite rulers.

As recorded in the ancient text Han Shu (the book of Han), these farmers’ calloused hands held bamboo scrolls – ancient “tweets” accusing the bureaucrats of hoarding grain while the farmers’ children gnawed tree bark. The rebellion’s firebrand warlord leader, Chong Fan, roared: “Drain the paddies!”

Within weeks, the Red Eyebrows, as the protesters became known, had toppled local regimes, raided granaries and – for a fleeting moment – shattered the empire’s rigid hierarchy.

The Han dynasty of China (202BC-AD220) was one of the most developed civilisations of its time, alongside the Roman empire. Its development of cheaper and sharper iron ploughs enabled the gathering of unprecedented harvests of grain.

But instead of uplifting the farmers, this technological revolution gave rise to agrarian oligarchs who hired ever-more officials to govern their expanding empire. Soon, bureaucrats earned 30 times more than those tilling the soil.

Windmemories via Wikimedia, CC BY-NC-SA

And when droughts struck, the farmers and their families starved while the empire’s elites maintained their opulence. As a famous poem from the subsequent Tang dynasty put it: “While meat and wine go to waste behind vermilion gates, the bones of the frozen dead lie by the roadside.”

Two millennia later, the role of technology in increasing inequality around the world remains a major political and societal issue. AI-driven “technology panic” – exacerbated by the disruptive efforts of Donald Trump’s new administration in the US – gives the feeling that everything has been upended. New tech is destroying old certainties; populist revolt is shredding the political consensus.

And yet, as we stand at the edge of this technological cliff, seemingly peering into a future of AI-induced job apocalypses, history whispers: “Calm down. You’ve been here before.”

The link between technology and inequality

Technology is humanity’s cheat code to break free from scarcity. The Han dynasty’s iron plough didn’t just till soil; it doubled crop yields, enriching landlords and swelling tax coffers for emperors while – initially, at least – leaving peasants further behind. Similarly, Britain’s steam engine didn’t just spin cotton; it built coal barons and factory slums. Today, AI isn’t just automating tasks; it’s creating trillion-dollar tech fiefdoms while destroying myriads of routine jobs.

Technology amplifies productivity by doing more with less. Over centuries, these gains compound, raising economic output and increasing incomes and lifespans. But each innovation reshapes who holds power, who gets rich – and who gets left behind.

As the Austrian economist Joseph Schumpeter warned during the second world war, technological progress is never a benign rising tide that lifts all boats. It’s more like a tsunami that drowns some and deposits others on golden shores, amid a process he called “creative destruction”.

Wikimedia Commons, CC BY

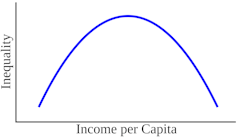

A decade later, Russian-born US economist Simon Kuznets proposed his “inverted-U of inequality”, the Kuznets curve. For decades, this offered a reassuring narrative for citizens of democratic nations seeking greater fairness: inequality was an inevitable – but temporary – price of technological progress and the economic growth that comes with it.

In recent years, however, this analysis has been sharply questioned. Most notably, French economist Thomas Piketty, in a reappraisal of more than three centuries of data, argued in 2013 that Kuznets had been misled by historical fluke. The postwar fall in inequality he had observed was not a general law of capitalism, but a product of exceptional events: two world wars, economic depression, and massive political reforms.

In normal times, Piketty warned, the forces of capitalism will always tend to make the rich richer, pushing inequality ever higher unless checked by aggressive redistribution.

So, who’s correct? And where does this leave us as we ponder the future in this latest, AI-driven industrial revolution? In fact, both Kuznets and Piketty were working off quite narrow timeframes in modern human history. Another country, China, offers the chance to chart patterns of growth and inequality over a much longer period – due to its historical continuity, cultural stability, and ethnic uniformity.

The Insights section is committed to high-quality longform journalism. Our editors work with academics from many different backgrounds who are tackling a wide range of societal and scientific challenges.

Unlike other ancient civilisations such as the Egyptians and Mayans, China has maintained a unified identity and unique language for more than 5,000 years, allowing modern scholars to trace thousand-year-old economic records. So, with colleagues Qiang Wu and Guangyu Tong, I set out to reconcile the ideas of Kuznets and Piketty by studying technological growth and wage inequality in imperial China over 2,000 years – back beyond the birth of Jesus.

To do this, we scoured China’s extraordinarily detailed dynastic archives, including the Book of Han (AD111) and Tang Huiyao (AD961), in which meticulous scribes recorded the salaries of different ranking officials. And here is what we learned about the forces – good and bad, corrupt and selfless – that most influenced the rise and fall of inequality in China over the past two millennia.

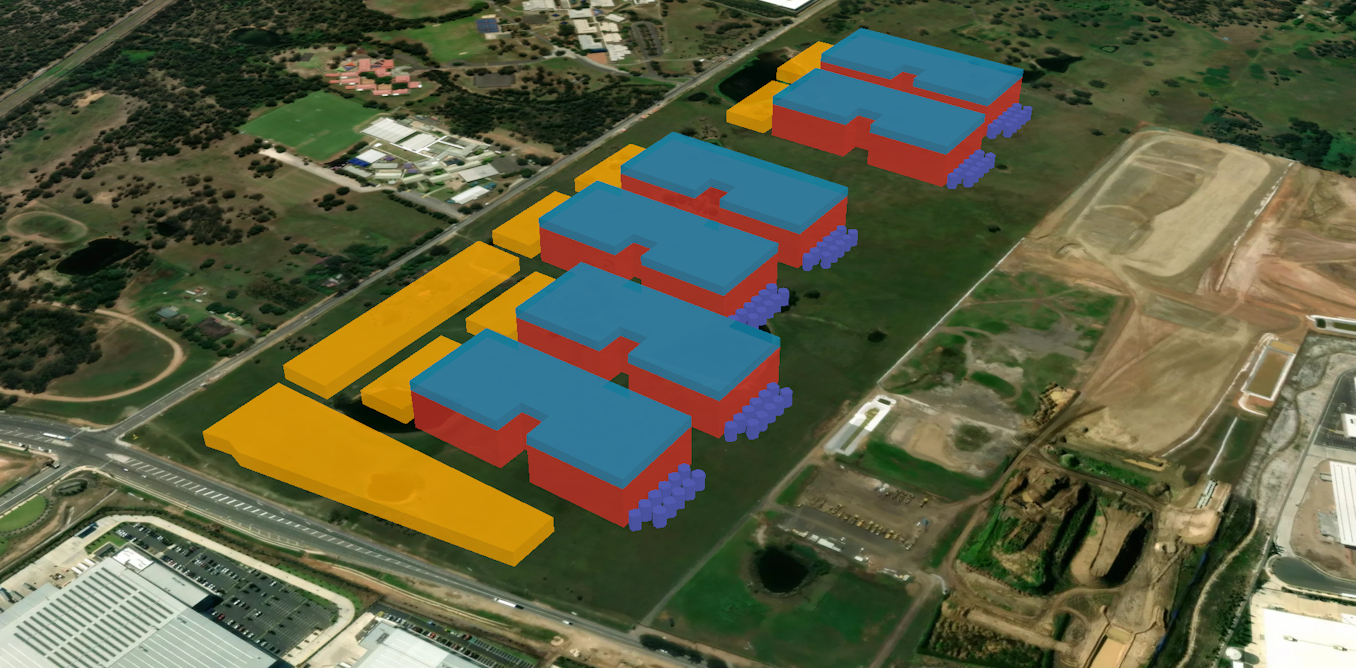

Chinese dynasties and their most influential technologies:

Peng Zhou, CC BY-NC-SA

China’s cycles of growth and inequality

One of the challenges of assessing wage inequality over thousands of years is that people were paid different things at different times – such as grain, silk, silver and even labourers.

The Book of Han records that “a governor’s annual grain salary could fill 20 oxcarts”. Another entry describes how a mid-ranking Han official’s salary included ten servants tasked solely with polishing his ceremonial armour. Ming dynasty officials had their meagre wages supplemented with gifts of silver, while Qing elites hid their wealth in land deals.

Yeu Ninje via Wikimedia, CC BY-NC-SA

To enable comparison over two millennia, we invented a “rice standard” – akin to the gold standard that was the basis of the international monetary system for a century from the 1870s. Rice is not just a staple of Chinese diets, it has been a stable measure of economic life for thousands of years.

While rice’s dominion began around 7,000BC in the Yangtze river’s fertile marshes, it was not until the Han dynasty that it became the soul of Chinese life. Farmers prayed to the “Divine Farmer” for bountiful harvests, and emperors performed elaborate ploughing rituals to ensure cosmic harmony. A Tang dynasty proverb warned: “No rice in the bowl, bones in the soil.”

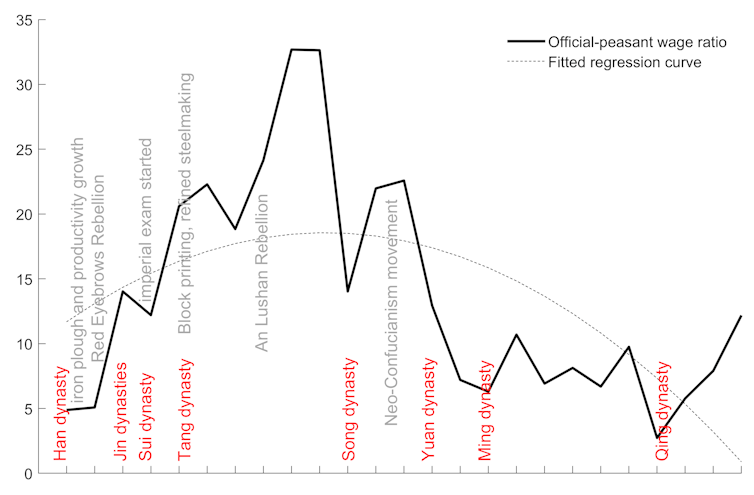

Using price records, we converted every recorded salary – whether paid in silk, silver, rent or servants – into its rice equivalent. We could then compare the “real rice wages” of two categories of people we called either “officials” or “peasants” (including farmers), as a way of tracking levels of inequality over the two millennia since the start of the Han dynasty in 202BC. This chart shows how real-wage inequality in China rose and fell over the past 2,000 years, according to our rice-based analysis.

Official-peasant wage ratio in imperial China over 2,000 years:

Peng Zhou, CC BY-SA

The chart’s black line describes a tug-of-war between growth and inequality over the past two millennia. We found that, across each major dynasty, there were four key factors driving levels of inequality in China: technology (T), institutions (I), politics (P), and social norms (S). These followed the following cycle with remarkable regularity.

1. Technology triggers an explosion of growth and inequality

During the Han dynasty, new iron-working techniques led to better ploughs and irrigation tools. Harvests boomed, enabling the Chinese empire to balloon in both territory and population. But this bounty mostly went to those at the top of society. Landlords grabbed fields, bureaucrats gained privileges, while ordinary farmers saw precious little reward. The empire grew richer – but so did the gap between high officials and the peasant majority.

Even when the Han fell around AD220, the rise of wage inequality was barely interrupted. By the time of the Tang dynasty (AD618–907), China was enjoying a golden age. Silk Road trade flourished as two more technological leaps had a profound impact on the country’s fortunes: block printing and refined steelmaking.

Block printing enabled the mass production of books – Buddhist texts, imperial exam guides, poetry anthologies – at unprecedented speed and scale. This helped spread literacy and standardise administration, as well as sparking a bustling market in bookselling.

Meanwhile, refined steelmaking boosted everything from agricultural tools to weaponry and architectural hardware, lowering costs and raising productivity. With a more literate populace and an abundance of stronger metal goods, China’s economy hit new heights. Chang’an, then China’s cosmopolitan capital, boasted exotic markets, lavish temples, and a swirl of foreign merchants enjoying the Tang dynasty’s prosperity.

While the Tang dynasty marked the high-water mark for levels of inequality in Chinese history, subsequent dynasties would continue to wrestle with the same core dilemma: how do you reap the benefits of growth without allowing an overly privileged – and increasingly corrupt – bureaucratic class to push everyone else into peril?

2. Institutions slow the rise of inequality

Throughout the two millennia, some institutions played an important role in stabilising the empire after each burst of growth. For example, to alleviate tensions between emperors, officials and peasants, imperial exams known as “Ke Ju” were introduced during the Sui dynasty (AD581-618). And by the time of the Song dynasty (AD960-1279) that followed the demise of the Tang, these exams played a dominant role in society.

They addressed high levels of inequality by promoting social mobility: ordinary civilians were granted greater opportunities to ascend the income ladder by achieving top marks. This induced greater competition among officials – and strengthened emperors’ authority over them in the later dynasties. As a result, both the wages of officials and wage inequality went down as their bargaining power gradually diminished.

However, the rise of each new dynasty was also marked by a growth of bureaucracy that led to inefficiencies, favouritism and bribery. Over time, corrupt practices took root, eroding trust in officialdom and heightening wage inequality as many officials commanded informal fees or outright bribes to sustain their lifestyles.

As a result, while the emergence of certain institutions was able to put a break on rising inequality, it typically took another powerful – and sometimes highly destructive – factor to start reducing it.

The History Collection/Alamy Stock Photo

3. Political infighting and external wars reduce inequality

Eventually, the rampant rise in inequality seen in almost every major Chinese dynasty bred deep tensions – not only between the upper and lower classes, but even between the emperor and their officials.

These pressures were heightened by the pressures of external conflict, as each dynasty waged wars in pursuit of further growth. The Tang’s three century-rule featured conflicts such as the Eastern Turkic-Tang war (AD626), the Baekje-Goguryeo-Silla war (666), and the Arab-Tang battle of Talas (751).

The resulting demand for more military spending drained imperial coffers, forcing salary cuts for soldiers and tax hikes on the peasants – breeding resentment among both that sometimes led to popular uprisings. In a desperate bid for survival, the imperial court then slashed officials’ pay and stripped away their bureaucratic perks.

The result? Inequality plummeted during these times of war and rebellion – but so did stability. Famine was rife, frontier garrisons mutinied, and for decades, warlords carved out territories while the imperial centre floundered.

So, this shrinking wage gap cannot be said to have resulted in a happier, more stable society. Rather, it reflected the fact that everyone – rich and poor – was worse off in the chaos. During the final imperial dynasty, the Qing (from the end of the 17th century), real-terms GDP per person was dropping to levels that had last been seen at the start of the Han dynasty, 2,000 years earlier.

4. Social norms emphasise harmony, preserve privilege

One other common factor influencing the rise and fall of inequality across China’s dynasties was the shared rules and expectations that developed within each society.

A striking example is the social norms rooted in the philosophy of Neo-Confucianism, which emerged in the Song dynasty at the end of the first millennium – a period sometimes described as China’s version of the Renaissance. It blended the moral philosophy of classical Confucianism – created by the philosopher and political theorist Confucius during the Zhou dynasty (1046-256BC) – with metaphysical elements drawn from both Buddhism and Daoism.

Art Collection/Alamy Stock Photo

Neo-Confucianism emphasised social harmony, hierarchical order and personal virtue – values that reinforced imperial authority and bureaucratic discipline. Unsurprisingly, it quickly gained the support of emperors keen to ensure control of their people, and became the mainstream school of thought in the Ming and Qing dynasties.

However, Neo-Confucianist thinking proved a double-edged sword. Local gentry hijacked this moral authority to fortify their own power. Clan leaders set up Confucian schools and performed elaborate ancestral rites, projecting themselves as guardians of tradition.

Over time, these social norms became rigid. What had once fostered order and legitimacy became brittle dogma, more useful for preserving privilege than guiding reform. Neo-Confucian ideals evolved into a protective veil for entrenched elites. When the weight of crisis eventually came, they offered little resilience.

The last dynasty

China’s final imperial dynasty, the Qing, collapsed under the weight of multiple uprisings both from within and without. Despite achieving impressive economic growth during the 18th century – fuelled by agricultural innovation, a population boom, and the roaring global trade in tea and porcelain – levels of inequality exploded, in part due to widespread corruption.

The infamous government official Heshen, widely regarded as the most corrupt figure in the Qing dynasty, amassed a personal fortune reckoned to exceed the empire’s entire annual revenue (one estimate suggests he amassed 1.1 billion taels of silver, equivalent to around US$270 billion (£200bn), during his lucrative career).

Imperial institutions failed to restrain the inequality and moral decay that the Qing’s growth had initially masked. The mechanisms that once spurred prosperity – technological advances, centralised bureaucracy and Confucian moral authority – eventually ossified, serving entrenched power rather than adaptive reform.

When shocks like natural disasters and foreign invasions struck, the system could no longer respond. The collapse of the empire became inevitable – and this time there was no groundbreaking technology to enable a new dynasty to take the Qing’s place. Nor were there fresh social ideals or revitalised institutions capable of rebooting the imperial model. As foreign powers surged ahead with their own technological breakthroughs, China’s imperial system collapsed under its own weight. The age of emperors was over.

UtCon Collection/Alamy Stock Photo

The world had turned. As China embarked on two centuries of technological and economic stagnation – and political humiliation at the hands of Great Britain and Japan – other nations, led first by Britain and then the US, would step up to build global empires on the back of new technological leaps.

In these modern empires, we see the same four key influences on their cycles of growth and inequality – technology, institutions, politics and social norms – but playing out at an ever-faster rate. As the saying goes: history does not repeat itself, but it often rhymes.

Rule Britannia

If imperial China’s inequality saga was written in rice and rebellions, Britain’s industrial revolution featured steam and strikes. In Lancashire’s “satanic mills”, steam engines and mechanised looms created industrialists so rich that their fortunes dwarfed small nations.

In 1835, social observer Andrew Ure enthused: “Machinery is the grand agent of civilisation.” Yet for many decades, the steam engines, spinning jennies and railways disproportionately enriched the new industrial class, just as in the Han dynasty of China 2,000 years earlier. The workers? They inhaled soot, lived in slums – and staged Europe’s first symbolic protest when the Luddites began smashing their looms in 1811.

Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

During the 19th century, Britain’s richest 1% hoarded as much as 70% of the nation’s wealth, while labourers toiled 16-hour days in mills. In cities like Manchester, child workers earned pennies while industrialists built palaces.

But as inequality peaked in Britain, the backlash brewed. Trade unions formed (and became legal in 1824) to demand fair wages. Reforms such as the Factory Acts (1833–1878) banned child labour and capped working hours.

Although government forces intervened to suppress the uprisings, unrest such as the 1830 Swing Riots and 1842 General Strike exposed deep social and economic inequalities. By 1900, child labour was banned and pensions had been introduced. The 1900 Labour Representation Committee (later the Labour Party) vowed to “promote legislation in the direct interests of labour” – a striking echo of how China’s imperial exams had attempted to open paths to power.

Slowly, the working class saw some improvement: real wages for Britain’s poorest workers gradually increased over the latter half of the 19th century, as mass production lowered the cost of goods and expanding factory employment provided a more stable livelihood than subsistence farming.

And then, two world wars flattened Britain’s elite – the Blitz didn’t discriminate between rich and poor neighbourhoods. When peace finally returned, the Beveridge Report gave rise to the welfare state: the NHS, social housing, and pensions.

Income inequality plummeted as a result. The top 1%’s share fell from 70% to 15% by 1979. While China’s inequality fell via dynastic collapse, Britain’s decline resulted from war-driven destruction, progressive taxation, and expansive social reforms.

Wealth share of top 1% in the UK

Peng Zhou, CC BY-SA

However, from the 1980s onwards, inequality in Britain has begun to rise again. This new cycle of inequality has coincided with another technological revolution: the emergence of personal computers and information technology — innovations that fundamentally transformed how wealth was created and distributed.

The era was accelerated by deregulation, deindustrialisation and privatisation — policies associated with former prime minister Margaret Thatcher, that favoured capital over labour. Trade unions were weakened, income taxes on the highest earners were slashed, and financial markets were unleashed. Today, the richest 1% of UK adults own more 20% of the country’s total wealth.

The UK now appears to be in the worst of both worlds – wrestling with low growth and rising inequality. Yet renewal is still within reach. The current UK government’s pledge to streamline regulation and harness AI could spark fresh growth – provided it is coupled with serious investment in skills, modern infrastructure, and inclusive institutions geared to benefit all workers.

At the same time, history reminds us that technology is a lever, not a panacea. Sustained prosperity comes only when institutional reform and social attitudes evolve in step with innovation.

The American century

While China’s growth-and-inequality cycles unfolded over millennia and Britain’s over centuries, America’s story is a fast-forward drama of cycles lasting mere decades. In the early 20th century, several waves of new technology widened the gap between rich and poor dramatically.

By 1929, as the world teetered on the edge of the Great Depression, John D. Rockefeller had amassed such a vast fortune – valued at roughly 1.5% of America’s entire GDP – that newspapers hailed him the world’s first billionaire. His wealth stemmed largely from pioneering petroleum and petrochemical ventures including Standard Oil, which dominated oil refining in an age when cars and mechanised transport were exploding in popularity.

Yet this period of unprecedented riches for a handful of magnates coincided with severe imbalances in the broader US economy. The “roaring Twenties” had boosted consumerism and stock speculation, but wage growth for many workers lagged behind skyrocketing corporate profits. By 1929, the top 1% of Americans owned more than a third of the nation’s income, creating a precariously narrow base of prosperity.

When the US stock market crashed in October 1929, it laid bare how vulnerable the system was to the fortunes of a tiny elite. Millions of everyday Americans – living without adequate savings or safeguards – faced immediate hardship, ushering in the Great Depression. Breadlines snaked through city streets, and banks collapsed under waves of withdrawals they could not meet.

National Archives at College Park via Wikimedia

In response, President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal reshaped American institutions. It introduced unemployment insurance, minimum wages, and public works programmes to support struggling workers, while progressive taxation – with top rates exceeding 90% during the second world war. Roosevelt declared: “The test of our progress is not whether we add more to the abundance of those who have much – it is whether we provide enough for those who have too little.”

In a different way to the UK, the second world war proved a great leveller for the US – generating millions of jobs and drawing women and minorities into industries they’d long been excluded from. After 1945, the GI Bill expanded education and home ownership for veterans, helping to build a robust middle class. Although access remained unequal, especially along racial lines, the era marked a shift toward the norm that prosperity should be shared.

Meanwhile, grassroots movements led by figures like Martin Luther King Jr. reshaped social norms about justice. In his lesser-quoted speeches, King warned that “a dream deferred is a dream denied” and launched the Poor People’s Campaign, which demanded jobs, healthcare and housing for all Americans. This narrowing of income distribution during the post-war era was dubbed the “Great Compression” – but it did not last.

As oil crises of the 1970s marked the end of the preceding cycle of inequality, another cycle began with the full-scale emergence of the third industrial revolution, powered by computers, digital networks and information technology.

Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-ND

As digitalisation transformed business models and labour markets, wealth flowed to those who owned the algorithms, patents and platforms – not those operating the machines. Hi-tech entrepreneurs and Wall Street financiers became the new oligarchs. Stock options replaced salaries as the true measure of success, and companies increasingly rewarded capital over labour.

By the 2000s, the wealth share of the richest 1% climbed to 30% in the US. The gap between the elite minority and working majority widened with every company stock market launch, hedge fund bonus and quarterly report tailored to shareholder returns.

But this wasn’t just a market phenomenon – it was institutionally engineered. The 1980s ushered in the age of (Ronald) Reaganomics, driven by the conviction that “government is not the solution to our problem; government is the problem”. Following this neoliberalist philosophy, taxes on high incomes were slashed, capital gains were shielded, and labour unions were weakened.

Deregulation gave Wall Street free rein to innovate and speculate, while public investment in housing, healthcare and education was curtailed. The consequences came to a head in 2008 when the US housing market collapsed and the financial system imploded.

The Global Financial Crisis that followed exposed the fragility of a deregulated economy built on credit bubbles and concentrated risk. Millions of people lost their homes and jobs, while banks were rescued with public money. It marked an economic rupture and a moral reckoning – proof that decades of pro-market policies had produced a system that privatised gain and socialised loss.

Inequality, long growing in the background, now became a glaring, undeniable fault line in American life – and it has remained that way ever since.

Fig 5. Wealth share and income share of top 1% in the US

Peng Zhou, CC BY-SA

So is the US proof that the Kuznets model of inequality is indeed wrong? While the chart above shows inequality has flattened in the US since the 2008 financial crisis, there is little evidence of it actually declining. And in the short term, while Donald Trump’s tariffs are unlikely to do much for growth in the US, his low-tax policies won’t do anything to raise working-class incomes either.

The story of “the American century” is a dizzying sequence of technological revolutions – from transport and manufacturing to the internet and now AI – crashing one atop the other before institutions, politics or social norms could catch up. In my view, the result is not a broken cycle but an interrupted one. Like a wheel that never completes its turn, inequality rises, reform stutters – and a new wave of disruption begins.

Our unequal AI future?

Like any technological explosion, AI’s potential is dual-edged. Like the Tang dynasty’s bureaucrats hoarding grain, today’s tech giants monopolise data, algorithms and computing power. Management consultant firm McKinsey has predicted that algorithms could automate 30% of jobs by 2030, from lorry drivers to radiologists.

Yet AI also democratises: ChatGPT tutors students in Africa while open-source models such as DeepSeek empower worldwide startups to challenge Silicon Valley’s oligarchy.

The rise of AI isn’t just a technological revolution – it’s a political battleground. History’s empires collapsed when elites hoarded power; today’s fight over AI mirrors the same stakes. Will it become a tool for collective uplift like Britain’s post-war welfare state? Or a weapon of control akin to Han China’s grain-hoarding bureaucrats?

The answer hinges on who wins these political battles. In 19th-century Britain, factory owners bribed MPs to block child labour laws. Today, Big Tech spends billions lobbying to neuter AI regulation.

Meanwhile, grassroots movements like the Algorithmic Justice League demand bans on facial recognition in policing, echoing the Luddites who smashed looms not out of technophobia but to protest exploitation. The question is not if AI will be regulated but who will write the rules: corporate lobbyists or citizen coalitions.

The real threat has never been the technology itself, but the concentration of its spoils. When elites hoard tech-driven wealth, social fault-lines crack wide open – as happened more than 2,000 years ago when the Red Eyebrows marched against Han China’s agricultural monopolies.

To be human is to grow – and to innovate. Technological progress raises inequality faster than incomes, but the response depends on how people band together. Initiatives like “Responsible AI” and “Data for All” reframe digital ethics as a civil right, much like Occupy Wall Street exposed wealth gaps. Even memes – like TikTok skits mocking ChatGPT’s biases – shape public sentiment.

There is no simple path between growth and inequality. But history shows our AI future isn’t preordained in code: it’s written, as always, by us.

For you: more from our Insights series:

To hear about new Insights articles, join the hundreds of thousands of people who value The Conversation’s evidence-based news. Subscribe to our newsletter.

The post “What 2,000 years of Chinese history reveals about today’s AI-driven technology panic – and the future of inequality” by Peng Zhou, Professor of Economics, Cardiff University was published on 04/24/2025 by theconversation.com