Imagine you had an unlimited budget for individual tutors offering hyper-personalised courses that maximised learners’ productivity and skills development. This summer I previewed this idea – with a ridiculous and solipsistic test.

I asked an AI tutor agent to play the role of me, an Oxford lecturer on media and AI, and teach me a personal master’s course, based entirely on my own work.

I set up the agent via an off-the-shelf ChatGPT tool hosted on the Azure-based Nebula One platform, with a prompt to research and impersonate me, then build personalised material based on what I already think. I didn’t tell the large language model (LLM) what to read or do anything else to enhance its capabilities, such as giving it access to learning materials that aren’t publicly available online.

The agent’s course in media and AI was well structured – a term-long, original six-module journey into my own collected works that I had never devised, but admit I would have liked to.

It was interactive and rapid-fire, demanding mental acuity via regular switches in formats. It was intellectually challenging, like good Oxford tutorials should be. The agent taught with rigour, giving instant responses to anything I asked. It had a powerful understanding of the fast-evolving landscape of AI and media through the same lens as me, but had done more homework.

This was apparently fed by my entire multimedia output – books, speeches, articles, press interviews, even university lectures I had no idea had even been recorded, let alone used to train GPT-4 or GPT-5.

The course was a great learning experience, even though I supposedly knew it all already. So in the inevitable student survey, I gave the agentic version of me well-deserved, five-star feedback.

For instance, in a section discussing the ethics of non-playing characters (NPCs) in computer games, it asked:

If NPCs are generated by AI, who decides their personalities, backgrounds or morals? Could this lead to bias or stereotyping?

And:

If an AI NPC can learn and adapt, does it blur the line between character and “entity” [independent actor]?

These are great, philosophical questions, which will probably come to the fore when and if Grand Theft Auto 6 comes out next May. I’m psyched that the agentic me came up with them, even if the real me didn’t.

Agentic me also built on what real me does know. In film, it knew about bog-standard Adobe After Effects, which I had covered (it’s used for creating motion graphics and visual effects). But it added Nuke, a professional tool used to combine and manipulate visual effects in Avengers, which (I’m embarrased to say) I had never heard of.

The course reading list

So where did the agent’s knowledge of me come from? My publisher Routledge did a training data deal with Open AI, which I guess could cover my books on media, AI and live experience.

Unlike some authors, I’m up for that. My books guide people through an amazing and fast-moving subject, and I want them in the global conversation, in every format and territory possible (Turkish already out, Korean this month).

That availability has to extend to what is now potentially the most discoverable “language” of all, the one spoken by AI models. The priority for any writer who agrees with this should be AI optimisation: making their work easy for LLMs to find, process and use – much like search engine optimisation, but for AI.

To build on this, I further tested my idea by getting an agent powered by China’s Deep Seek to run a course on my materials. When I found myself less visible in its training corpus, it was hard not to take offence. There is no greater diss in the age of AI than a leading LLM deeming your book about AI irrelevant.

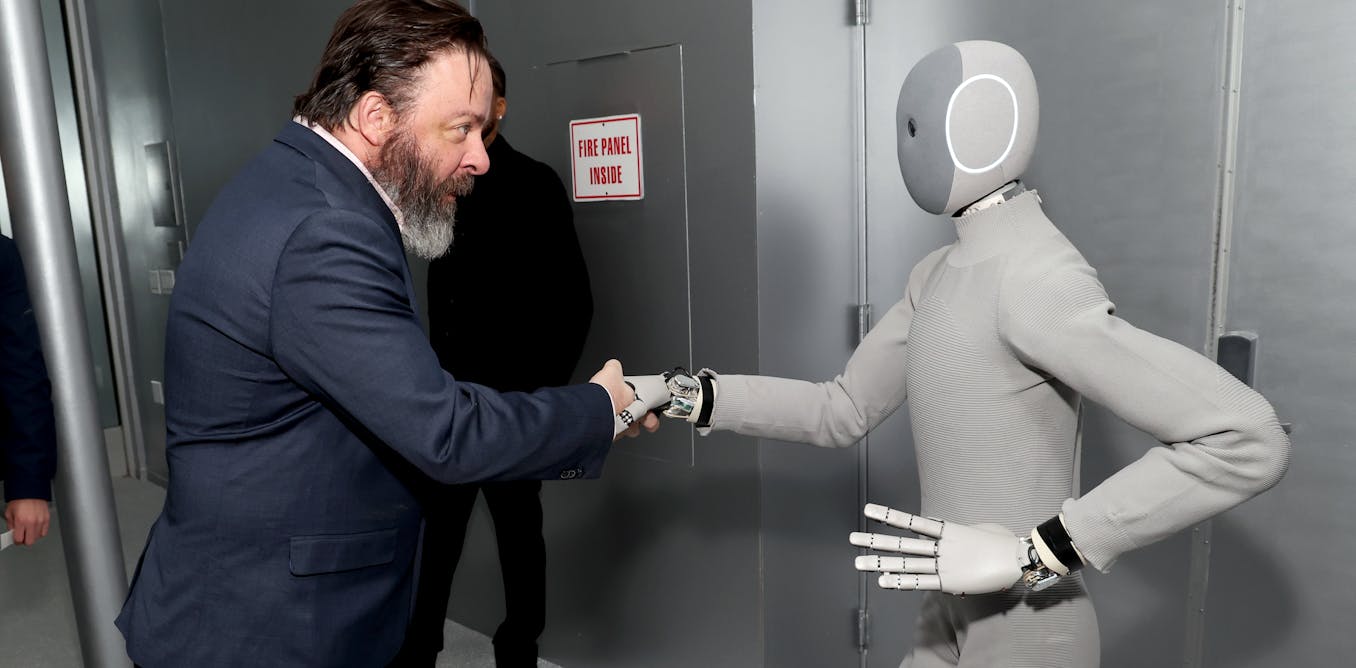

Vasilyev Alexandr

When I experimented with other AIs, they had issues getting their facts straight, which is very 2024. From Google’s Gemini 2.5 Pro I learned hallucinatory biographical details about myself like a role running media company The Runaway Collective.

When I asked Elon Musk’s Grok what my best quote was, it said: “Whatever your question, the answer is AI.” That’s a great line, but Google DeepMind’s Nobel-winning Demis Hassabis said it, not me.

Where we’re heading

This whole, self-absorbed summer diversion was clearly absurd, though not entirely. Agentic self-learning projects are quite possibly what university teaching actually needs: interactive, analytical, insightful and personalised. And there is some emerging research around the value. This German-led study found that AI-generated tuition helped to motivate secondary school students and benefited their exam revision.

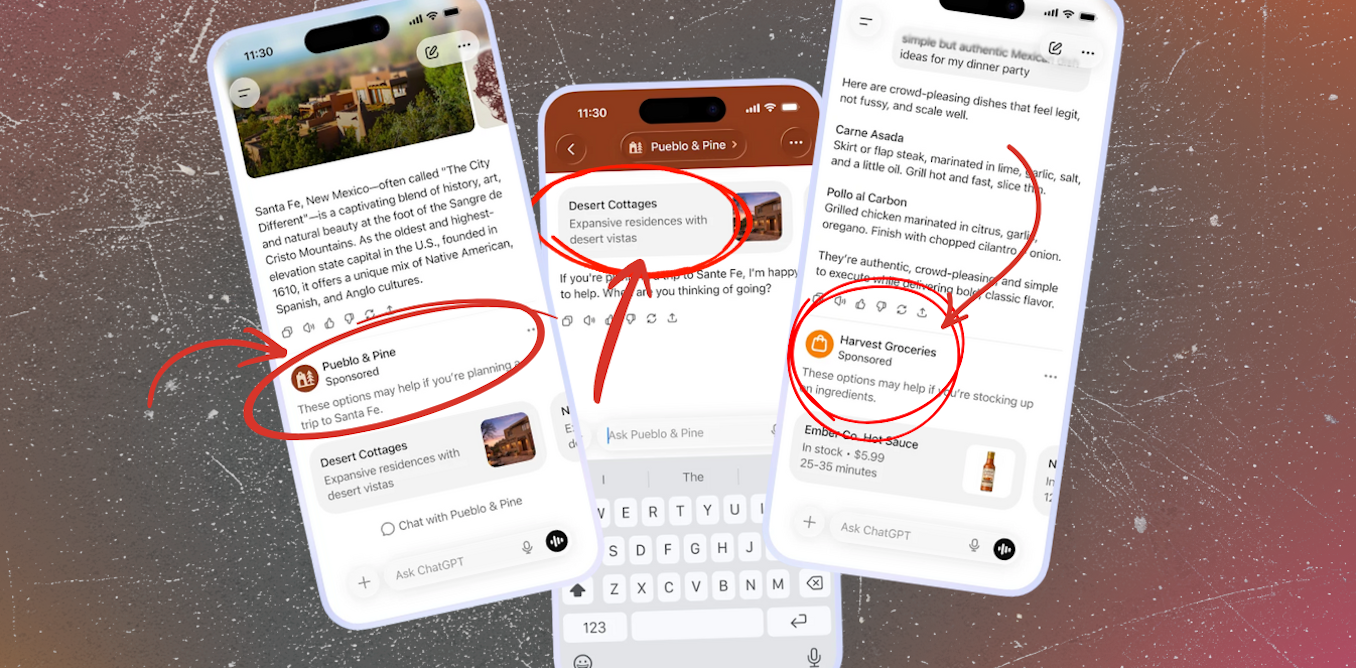

It won’t be long before we start to see this kind of real-time AI layer formally incorporated into school and university teaching. Anyone lecturing undergraduates will know that AI is already there. Students use AI transcription to take notes. Lecture content is ripped in seconds from these transcriptions, and will have trained a dozen LLMs within the year. To assist with writing essays, ChatGPT, Claude, Gemini and Deep Seek/Qwen are the sine qua non of Gen Z projects.

Metamorworks

But here’s the kicker. As AI becomes ever more central to education, the human teacher becomes more important, not less. They will guide the learning experience, bringing published works to the conceptual framework of a course, and driving in-person student engagement and encouragement. They can extend their value as personal AI tutors – via agents – for each student, based on individual learning needs.

Where do younger teachers fit in, who don’t have a back catalogue to train LLMs? Well, the younger the teacher, the more AI-native they are likely to be. They can use AI to flesh out their own conceptual vision for a course by widening the research beyond their own work, by prompting the agent on what should be included.

In AI, two alternate positions are often simultaneously true. AI is both emotionally intelligent and tone deaf. It is is both a glorified text predictor and a highly creative partner. It is costing jobs, yet creating them. It is dumbing us down, but also powering us up.

So too in teaching. AI threatens the learning space, yet can liberate powerful interaction. A prevailing wisdom is that it will make students dumber. But perhaps AI could actually be unlocking for students the next level of personalisation, challenge and motivation.

The post “I got an AI to impersonate me and teach me my own course – here’s what I learned about the future of education” by Alex Connock, Senior Fellow, Said Business School, University of Oxford was published on 08/18/2025 by theconversation.com