I come from dairy-farming stock. My grandfather, the original Harry Goldstein, owned a herd of dairy cows and a creamery in Louisville, Ky., that bore the family name. One fateful day in early April 1944, Harry was milking his cows when a heavy metallic part of his homemade milking contraption—likely some version of the then-popular Surge Bucket Milker—struck him in the abdomen, causing a blood clot that ultimately led to cardiac arrest and his subsequent demise a few days later, at the age of 48.

Fast forward 80 years and dairy farming is still a dangerous occupation. According to an analysis of U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics data done by the advocacy group Farmworker Justice, the U.S. dairy industry recorded 223 injuries per 10,000 full-time workers in 2020, almost double the rate for all of private industry combined. Contact with animals tops the list of occupational hazards for dairy workers, followed by slips, trips, and falls. Other significant risks include contact with objects or equipment, overexertion, and exposure to toxic substances. Every year, a few dozen dairy workers in the United States meet a fate similar to my grandfather’s, with 31 reported deadly accidents on dairy farms in 2021.

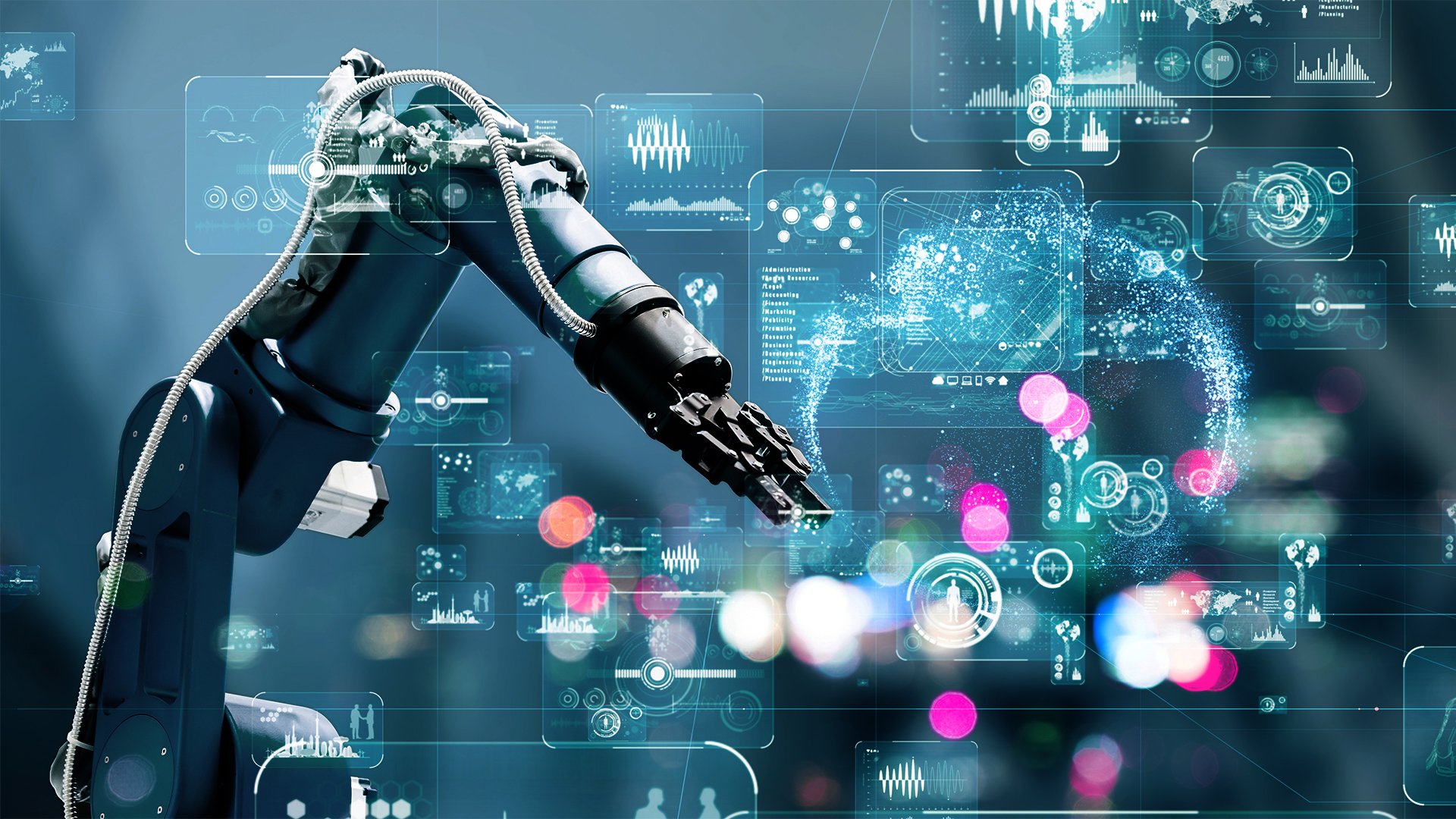

As Senior Editor Evan Ackerman notes in “Robots for Cows (and Their Humans)”, traditional dairy farming is very labor-intensive. Cows need to be milked at least twice per day to prevent discomfort. Conventional milking facilities are engineered for human efficiency, with systems like rotating carousels that bring the cows to the dairy workers.

The robotic systems that Netherlands-based Lely has been developing since the early 1990s are much more about doing things the bovine way. That includes letting the cows choose when to visit the milking robot, resulting in a happier herd and up to 10 percent more milk production.

Turns out that what’s good for the cows might be good for the humans, too. Another Lely bot deals with feeding, while yet another mops up the manure, the proximate cause of much of the slipping and sliding that can result in injuries. The robots tend to reset the cow–human relationship—it becomes less adversarial because the humans aren’t always there bossing the cows around.

Farmer well-being is also enhanced because the humans don’t have to be around to tempt fate, and they can spend time doing other things, freed up by the robot laborers. In fact, when Ackerman visited Lely’s demonstration farm in Schipluiden, Netherlands, to see the Lely robots in action, he says, “The original plan was for me to interview the farmer, and he was just not there at all for the entire visit while the cows were getting milked by the robots. In retrospect, that might have been the most effective way he could communicate how these robots are changing work for dairy farmers.”

The farmer’s absence also speaks volumes about how far dairy technology has evolved since my grandfather’s day. Harry Goldstein’s life was cut short by the very equipment he hacked to make his own work easier. Today’s dairy-farming innovations aren’t just improving efficiency—they’re keeping humans out of harm’s way entirely. In the dairy farms of the future, the most valuable safety features might simply be a barn resounding with the whirring of robots and moos of contentment.

The post “Bot Milk?” by Harry Goldstein was published on 05/01/2025 by spectrum.ieee.org