Where would we be without knowledge? Everything from the building of spaceships to the development of new therapies has come about through the creation, sharing, and validation of knowledge. It is arguably our most valuable human commodity.

From clay tablets to electronic tablets, technology has played an influential role in shaping human knowledge. Today we stand on the brink of the next knowledge revolution. It is one as big as — if not more so — the invention of the printing press, or the dawning of the digital age.

Generative artificial intelligence (AI) is a revolutionary new technology able to collect and summarise knowledge from across the internet at the click of a button. Its impact is already being felt from the classroom to the boardroom, the laboratory to the rainforest.

Looking back to look forward, what do we expect generative AI to do to our knowledge practices? And can we foresee how this may change human knowledge, for better or worse?

The power of the printing press

While printing technology had a huge immediate impact, we are still coming to grips with the full scale of its effects on society. This impact was largely due to its ability to spread knowledge to millions of people.

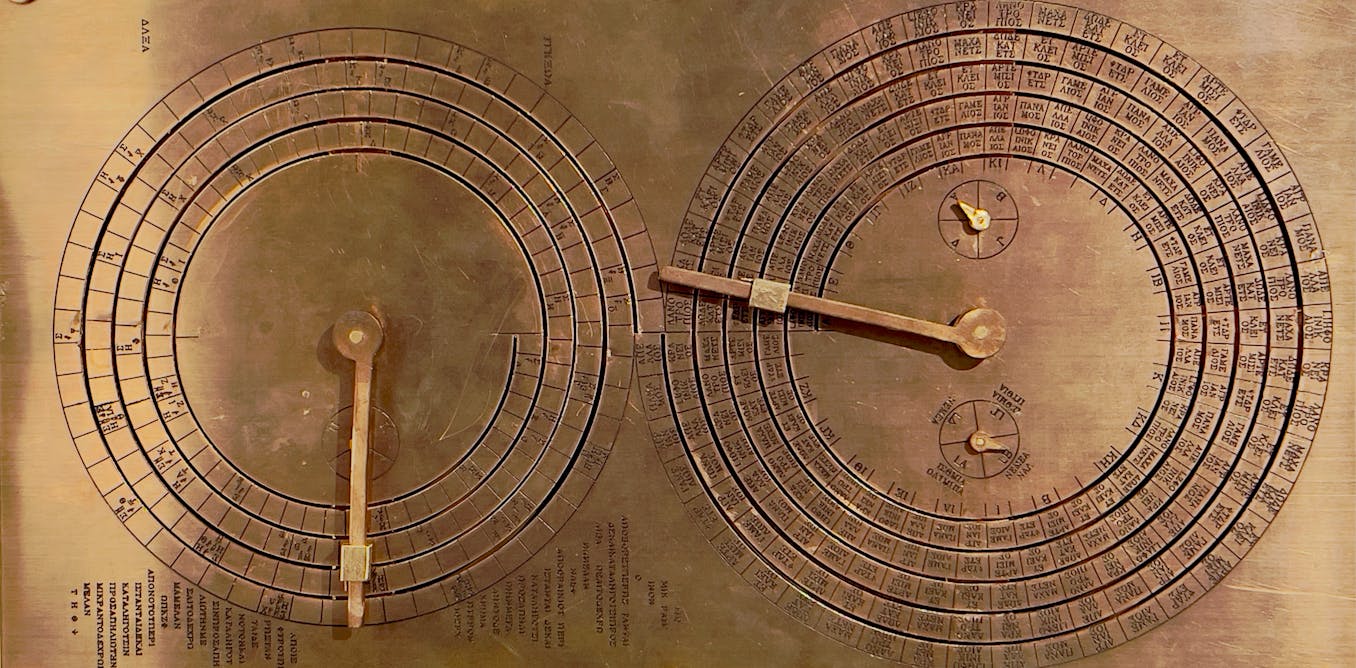

Of course, human knowledge existed before the printing press. Non-written forms of knowledge date back tens of thousands of years, and researchers are today demonstrating the advanced skills associated with verbal knowledge.

In turn, scribal culture played an integral role in ancient civilisations. Serving as a means to preserve legal codes, religious doctrines, or literary texts, scribes were powerful people who traded hand-written commodities for kings and nobles.

But it was the printing press – specifically the process of using movable type allowing for much cheaper and less labour-intensive book production – that democratised knowledge. This technology was invented in Germany around 1440 by goldsmith Johannes Gutenberg. Often described as the speaking of one-to-many, printing technology was able to provide affordable information to entire populations.

This exponential increase in knowledge dissemination has been associated with huge societal shifts, from the European Renaissance to the rise of the middle classes.

Daniel Chodowiecki/Wikipedia

The revolutionary potential of the digital age

The invention of the computer – and more importantly the connecting of multiple computers across the globe via the internet – saw the arrival of another knowledge revolution.

Often described as a new reality of speaking many-to-many, the internet provided a means for people to communicate, share ideas, and learn.

In the internet’s early days, USENET bulletin boards were digital chatrooms that allowed for unmediated crowd-sourced information exchange.

As internet users increased, the need for content regulation and moderation also grew. However, the internet’s role as the world’s largest open-access library has remained.

Masini/Shutterstock

The promise of generative AI

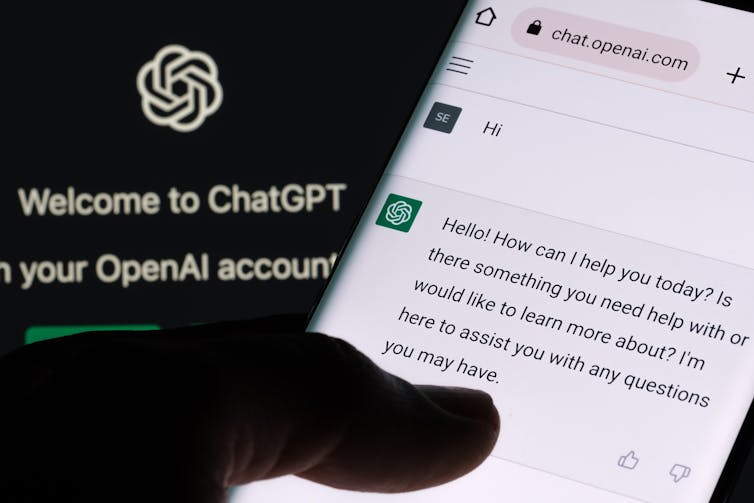

Generative AI refers to deep-learning models capable of generating human-like outputs, including text, images, video and audio. Examples include ChatGPT, Dall-E and DeepSeek.

Today, this new technology promises to function as our personal librarian, reducing our need to search for a book, let alone open its cover. Visiting physical libraries for information has been unnecessary for a while, but generative AI means we no longer need to even scroll through lists of electronic sources.

Trained on hundreds of billions of human words, AI can condense and synthesise vast amounts of information, across a variety of authors, subjects, or time periods. A user can pose any question to their AI assistant, and for the most part, will receive a competent answer. Generative AI can sometimes, however, “hallucinate”, meaning it will deliver unreliable or false information, instead of admitting it doesn’t know the answer.

Generative AI can also personalise its outputs, providing renditions in whatever language and tone required. Marketed as the ultimate democratiser of knowledge, the adaptation of information to suit a person’s interests, pace, abilities, and style is extraordinary.

But, as an increasingly prevalent arbitrator of our information needs, AI marks a new phase in the history of the relationship between knowledge and technology.

It challenges the very concept of human knowledge: its authorship, ownership and veracity. It also risks forfeiting the one-to-many revolution that was the printing press and the many-to-many potential that is the internet. In so doing, is generative AI inadvertently reducing the voices of many to the banality of one?

Ascannio/Shutterstock

Using generative AI wisely

Most knowledge is born of debate, contention, and challenge. It relies on diligence, reflexivity and application. The question of whether generative AI promotes these qualities is an open one, and evidence is so far mixed.

Some studies show it improves creative thinking, but others do not. Yet others show that while it might be helping individuals, it is ultimately diminishing our collective potential. Most educators are concerned it will dampen critical thinking.

More generally, research on “digital amnesia” tells us that we store less information in our heads today than we did previously due to our growing reliance on digital devices. And, relatedly, people and organisations are now increasingly dependent on digital technology.

Using history as inspiration, more than 2,500 years ago the Greek philosopher Socrates said that true wisdom is knowing when we know nothing.

If generative AI risks making us information rich but thinking poor (or individually knowledgeable but collectively ignorant), these words might be the one piece of knowledge we need right now.

The post “Technology has shaped human knowledge for centuries. Generative AI is set to transform it yet again” by Sarah Vivienne Bentley, Research Scientist, Responsible Innovation, Data61, CSIRO was published on 03/25/2025 by theconversation.com