In 1917, Sigmund Freud described three “narcissistic insults” that had been caused by science. These were moments of scientific breakthrough that showed humans that we are not as special as we once believed.

The first came with astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus’s discovery%5D) that we are not at the centre of the universe, because the sun rather than the Earth is at our solar system’s centre. It was followed by two more: the loss of humanity’s position as “the crown of creation” through Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution, and the loss of sovereignty over our own selves through the discovery of the power of the unconscious. The latter was Freud’s own work and, according to him, the toughest one of all.

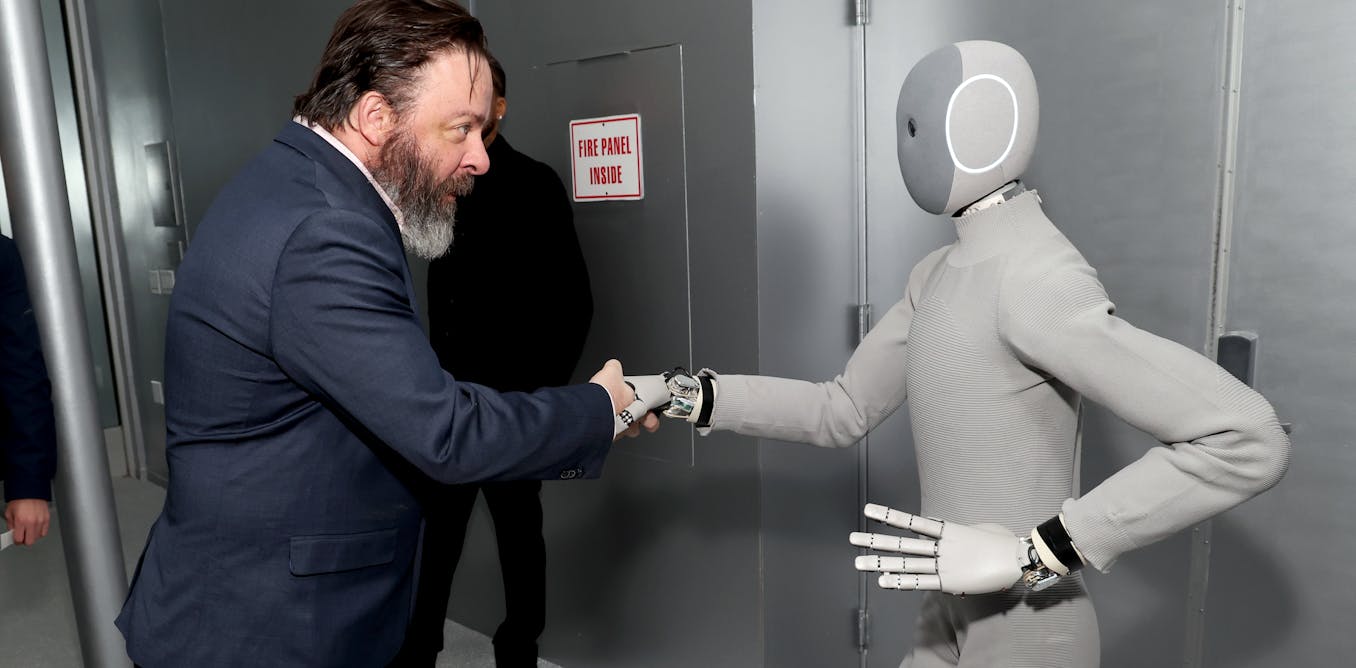

Had Freud heard of artificial intelligence (AI), I believe he would have been prompted to add a fourth. The cosmological, biological and psychological insults have now been followed by the intellectual. AI deals a fateful blow to our human self-understanding.

As a theologian, I’m particularly interested in the implications of this threat for our sense of spirituality. Generally speaking, humanity has coped quite well with the first three “narcissistic insults” described by Freud. But what cures are available for the wound of this most recent development?

1. Changing the language of AI

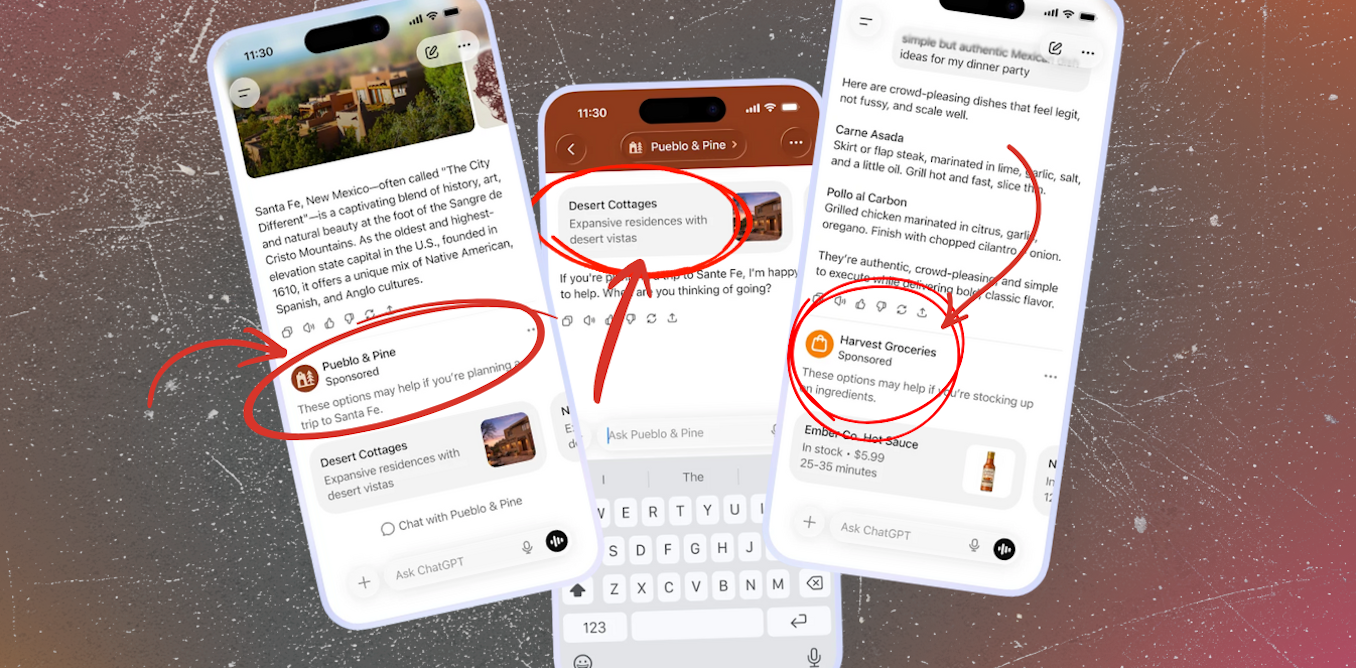

Even though the range and achievements of AI are breathtaking, the term “artificial intelligence” could be questioned to quell the damage it presents to our self-image. “Co-intelligence” may be more adequate, indicating that, for example, large language models should be used only as complementary to our own mental resources. This language softens the harshness.

2. Questioning the intelligence of AI

Some researchers have questioned the intelligence of AI by pointing out that a large language model merely is “a stochastic parrot”. This suggests that AI seems to have a deep understanding of what it conveys, but in reality, it’s just a system that combines linguistic patterns it has encountered in its extensive training data, based on probable associations, without any actual grasp of meaning.

“We are not going to be AI’s stupid pets,” wrote cognitive scientist Peter Gärdenfors. Rather than fearing AI, we should be fearful of ourselves, because, seduced by AI, we could give up the fruits of the Enlightenment.

Focusing on the differences between human intelligence and its artificial counterpart makes us understand that as long as collective human intelligence can judge the plausibility of AI output, the insult can be handled.

3. Speaking of ‘intelligences’ rather than intelligence

Instead of a single phenomenon, human intelligence can be understood as a variety of intelligences: artistic, personal and moral. They all come together in a mode of intelligence that is intuitive, socially embedded and holds special importance for spirituality – the opposite of a stochastic parrot.

Humans seek and find meaning even beyond ordinary reality, whereas AI is stuck in the “here”, in the profane. When a large language model creates nonsensical or inaccurate outputs, this is called a hallucination. Artificial intelligence hallucinates, human intelligence transcends.

In view of this integration of intelligences in humans, AI is inferior to human intelligence – at least for now.

Yes, but …

These attempts to address the insult of AI recognise that it functions differently from human intelligence. Unlike humans, AI has its identity in computation and statistics. But that does not mean that we need not fear. The speed, volume and complexity of data processing by AI can reach levels that render this difference irrelevant, because the output will count, rather than the way it is achieved.

Say I suffer from massive fear of death and my partner is too affected to be of any help, while my AI assistant shares advice that I experience as caring and valuable. Would it then matter what I call this thing (example one), whether it is indeed intelligent (example two) or how many intelligences it represents (example three)?

Experienced usefulness is likely to trump philosophical questions about the intelligence of AI systems. So what now?

Wavering between techno-messianism (AI will save us and the planet) and techno-dystopia (AI is the end of humanity) is an understandable reaction to the intellectual insult. Yet, uncritical embrace is socially irresponsible, and panic often leads to irrational actions or apathy.

AI development is quicker than adaptation of social and legal systems – especially when the law follows democratic principles. In the haze of this dilemma, transparency gets lost, lines of responsibility become blurred, consequences strike unexpectedly and unevenly. AI will change the way we think about knowledge, work, communication and integrity. It will create winners and losers in the labour market. Social unrest may arise. Without critical humanistic reflection, it’s possible that AI will fail to contribute to a good society for all.

In response, all sectors of society must cooperate. Technical and legal expertise is not enough. It is in civil society that existential questions are asked, and answers sought not only in calculations about power and economics or in legal and technical intricacies, but also in the cultural, philosophical and theological sources from which humanity has drawn orientation over centuries.

The hallmarks of western modernity – individualism, consumerism and secularism – will not suffice in face of AI’s narcissistic insult. Instead, human qualities such as relationality, transcendence, fallibility and responsibility are key.

Looking for something good? Cut through the noise with a carefully curated selection of the latest releases, live events and exhibitions, straight to your inbox every fortnight, on Fridays. Sign up here.

The post “Freud would have called AI a ‘narcissistic insult’ to humanity – here’s how we might overcome it” by Antje Jackelén, Senior Advisor and Systematic Theologian., Lund University was published on 08/19/2025 by theconversation.com