What does it mean to think, act and work as a Jewish professor when human freedoms are under siege and authoritarian power gains ground? And how can we draw on our Jewish identities to navigate the sweeping encroachment of new technologies like AI?

As communication scholars, colleagues and collaborators, we have spent a lot of time trying to answer these questions in our scholarship by taking cues from the intellectual lineage of our shared culture.

Read more:

Philosopher Hannah Arendt provokes us to rethink what education is for in the era of AI

Lately, Donald Trump’s administration has demonstrated a heavy investment in cataloguing and categorizing Jewish professors. In April, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) sent text messages to the personal cellphones of faculty and staff at Barnard College, asking them to self-identify as Jewish and/or Israeli. The text message also asked them to disclose any instances of antisemitic discrimination or harassment they had experienced.

Presumably, the text message inquiry itself was not recognized by its senders as an instance of such harassment.

(AP Photo/Seth Wenig, File)

We do not believe being a Jewish professor means silencing our students as they protest atrocities in Gaza, and it certainly doesn’t mean revoking their visas or deporting them. Rather, it means drawing upon the tools of our forebears to question systems of oppression, wherever and however they may arise.

We simultaneously occupy both privileged and marginal positions within the university and North American society at large. This makes us acutely aware of how fragile conditional tolerance is, and how quickly a list of names can be used to justify repression or violence.

Collection and use of data

As communication and media scholars, we’re often critical of how data are aggregated, stored and disseminated. The EEOC questionnaire concerns us because it reduces the complexities of Jewish identity and the profound harms of antisemitism to a handful of abstract and ideologically determined data points.

Our recent research on generative AI (genAI) and its incompatibility with Jewish cultural expression shows that meaningful efforts to combat antisemitism — and other forms of oppression — must centre the knowledge and experiences of affected communities.

Our research found that outputs of chatbots such as ChatGPT are unable to tell jokes in a Jewish comedic style without resorting to offensive tropes. In another forthcoming study, we argue that genAI is equally incapable of representing the multifaceted “intersectional identities” of Jewish people except by smashing together rudimentary cultural signifiers (such as rainbows for queerness or bagels for Jewishness).

In each case, these platforms rely on datasets to determine what Jewishness is, and these datasets originate from the narratives that other people tell about Jewish people, rather than the ones we tell about ourselves.

(Shutterstock)

Critical strategies

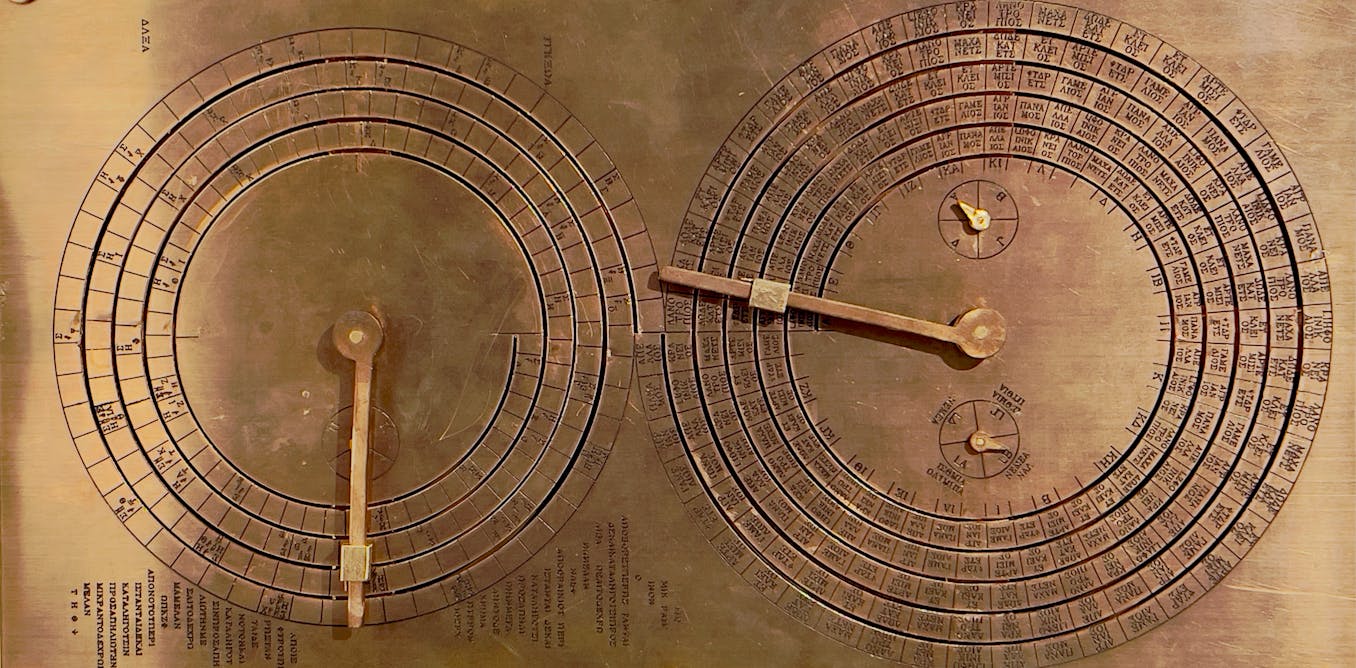

These platforms have increasingly become parts of daily life and communicative infrastructure. To investigate them, we adopted two critical strategies from our shared heritage as Ashkenazi Jews: kibbitzing and futzing.

Both terms are Yiddish. Kibbitzing is a lively, informal way of thinking and talking together. It’s somewhere between joking, arguing and exchanging ideas. It is grounded in our relationships, histories and biases; kibbitzing is how we make shared meaning together through many voices.

Kibbitzing values contradiction, humour and the messiness of human conversation. Unlike AI chatbots, which follow scripted, dialogic, question-and-answer routines based on quantifiable patterns in data, kibbitzing is unpredictable, non-linear and intentionally disorganized.

When we kibbitz, we build understanding by challenging one another and reflecting on what each of us brings to the table. In the age of genAI, kibbitzing offers a way to talk that is full of friction, laughter and deep, collective insight.

Futzing means messing around via hands-on experimentation, with no set agenda and no official guidance. This unstructured inquiry is an acknowledgement of Jews’ historical role as outsiders within European society. As we write in our forthcoming article, these practices reflect what social theorist Michel de Certeau calls “making do,” a tactical means of collective empowerment in a hostile society.

Using futzing as a methodology, we started exploring genAI, drawing on our curiosity to see what might happen by playing, testing and responding in real time.

Futz first, then kibbitz

Each of us futzed on our own at first, with no ambition to crack the code or reverse-engineer the algorithm. Later, when we began kibbitzing together, we realized our scattered efforts were actually circling around shared concerns. Futzing helped us see patterns, surprises and contradictions — things we might have missed with a more rigid approach. Kibbitzing helped us connect those patterns and reconcile the contradictions.

Drawing on our culture this way allows us to imagine inclusive, anti-oppressive Jewish epistemologies that respond to the complexity of the current political moment. Jewish identity — like all identities — is porous and resistant to fixed form. Our shared North American Ashkenazi identity is just one of many possible perspectives that comprise a broader identity of Jewishness.

That is not a problem to be solved. Rather, it is a strength and a bond between us. Readers may well see their own cultural traditions, vernaculars and ancestral practices in this light too, as techniques of resilience and joy in the face of hardship and oppression.

There is an irony here. The deeper we dig into the intellectual roots of our own culture, the more common ground we might discover with everyone else’s. And that makes us feel a whole lot safer than getting a text from the EEOC ever could.

The post “Experimenting with generative AI to kibbitz and futz towards more inclusive futures” by Nathaniel Laywine, Assistant Professor, Communication and Media Studies, York University, Canada was published on 06/01/2025 by theconversation.com