You can doubt just about anything. But there’s one thing you can know for sure: you are having thoughts right now.

This idea came to characterise the philosophical thinking of 17th century philosopher René Descartes. For Descartes, that we have thoughts may be the only thing we can be certain about.

But what exactly are thoughts? This is a mystery that has long troubled philosophers such as Descartes – and which has been given new life by the rise of artificial intelligence, as experts try to figure out whether machines can genuinely think.

Wikimedia

Two schools of thought

There are two main answers to the philosophical question of what thoughts are.

The first is that thoughts might be material things. Thoughts are just like atoms, particles, cats, clouds and raindrops: part and parcel of the physical universe. This position is known as physicalism or materialism.

The second view is that thoughts might stand apart from the physical world. They are not like atoms, but are an entirely distinct type of thing. This view is called dualism, because it takes the world to have a dual nature: mental and physical.

To better understand the difference between these views, consider a thought experiment.

Suppose God is building the world from scratch. If physicalism is true, then all God needs to do to produce thoughts is build the basic physical components of reality – the fundamental particles – and put in place the laws of nature. Thoughts should follow.

However, if dualism is true, then putting in place the basic laws and physical components of reality will not produce thoughts. Some non-physical aspects of reality will need to be added, as thoughts are something over and above all physical components.

Why be a materialist?

If thoughts are physical, what physical things are they? One plausible answer is they are brain states.

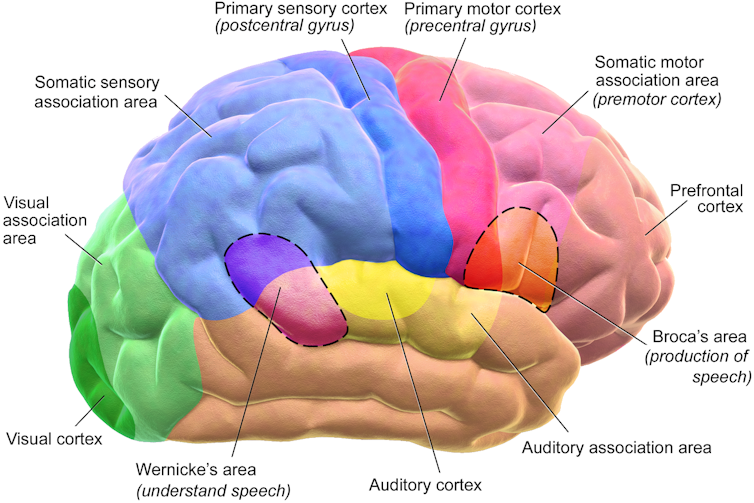

This answer underpins much of contemporary neuroscience and psychology. Indeed, it is the apparent link between brains and thoughts that makes materialism seem plausible.

There are many correlations between our brain states and our thoughts. Certain parts of the brain predictably “light up” when someone is in pain, or if they think about the past or future.

The hippocampus, located near the brain stem, appears to be linked to imaginative and creative thought, while the Broca’s area in the left hemisphere appears to be linked to speech and language.

Wikimedia

What explains these correlations? One answer is that our thoughts just are varying states of the brain. This answer, if correct, speaks in favour of materialism.

Why be a dualist?

That said, the correlations between brain states and thoughts are just that: correlations. We don’t have an explanation of how brain states – or any physical states for that matter – give rise to conscious thought.

There is a well-known correlation between striking a match and the match lighting. But in addition to the correlation, we also have an explanation for why the match is lit when struck. The friction causes a chemical reaction in the match head, which leads to a release of energy.

We have no comparable explanation for a link between thoughts and brain states. After all, there seem to be many physical things that don’t have thoughts. We have no idea why brain states give rise to thoughts and chairs don’t.

Shutterstock

The colour scientist

The thing we are most certain about – that we have thoughts – is still completely unexplained in physical terms. That’s not for a lack of effort. Neuroscience, philosophy, cognitive science and psychology have all been hard at work trying to crack this mystery.

But it gets worse: we may never be able to explain how thoughts arise from neural states. To understand why, consider this famous thought experiment by Australian philosopher Frank Jackson.

Mary lives her entire life in a black-and-white room. She has never experienced colour. However, she also has access to a computer which contains a complete account of every physical aspect of the universe, including all the physical and neurological details of experiencing colour. She learns all of this.

One day, Mary leaves the room and experiences colour for the first time. Does she learn anything new?

It is very tempting to think she does: she learns what it’s like to experience colour. But remember, Mary already knew every physical fact about the universe. So if she learns something new, it must be some non-physical fact. Moreover, the fact she learns comes through experience, which means there must be some non-physical aspect to experience.

If you think Mary learns something new by leaving the room, you must accept dualism to be true in some form. And if that’s the case, then we can’t provide an explanation of thought in terms of the brain’s functions, or so philosophers have argued.

Minds and machines

Settling the question of what thoughts are won’t completely settle the question of whether machines can think, but it would help.

If thoughts are physical, then there’s no reason, in principle, why machines couldn’t think.

If thoughts are not physical, however, it’s less clear whether machines could think. Would it be possible to get them “hooked up” to the non-physical in the right way? This would depend on how non-physical thoughts relate to the physical world.

Either way, pursuing the question of what thoughts are will likely have significant implications for how we think about machine intelligence, and our place in nature.

The post “Are our thoughts ‘real’? Here’s what philosophy says” by Sam Baron, Associate Professor, Philosophy of Science, The University of Melbourne was published on 03/05/2025 by theconversation.com