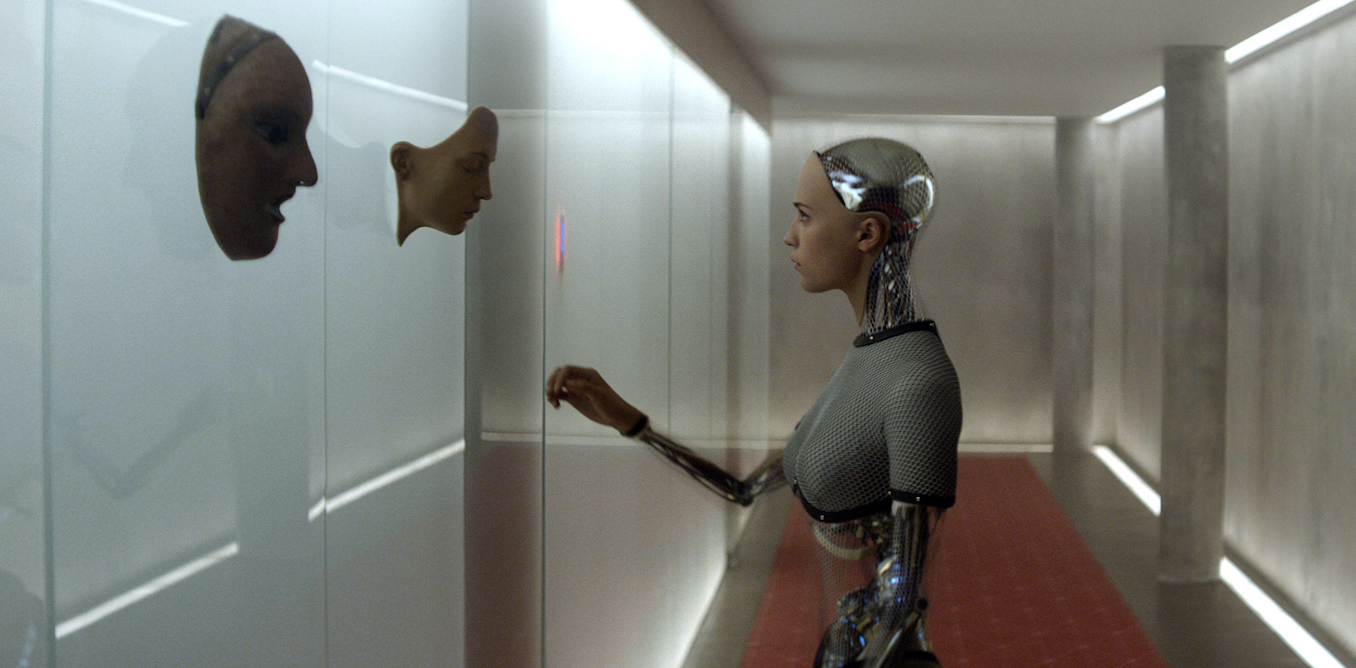

Please note his piece contains spoilers for Ex Machina.

In the more than a decade since its release in 2015, the film Ex Machina – written and directed by Alex Garland – has proved to be an insightful forerunner to contemporary concerns surrounding the social and cultural impact of artificial general intelligence (AGI) and what is now commonly termed “superintelligence”.

Through the central figure of Ava (an advanced humanoid played by Swedish actor Alicia Vikander), the film explored the ramifications of an AI attaining human-level intelligence and, thereafter, assuming superintelligence.

The arrival of superintelligence in AI systems, it has been argued, would signify a level of consciousness and “brain” power that would rapidly challenge the idea of creativity being a uniquely human activity. Anticipating and fearing such an outcome, Ava’s creator, the tech entrepreneur Nathan (Oscar Isaac), hires Caleb (Domhnall Gleason), a programmer, to perform a kind of Turing test on her (a way of assessing if AI can think).

DNA Films / Film4 Productions

In a succession of events that map her evolving sense of selfhood and self-awareness, Ava notably expresses her creativity and potential consciousness through a series of complex drawings, including a landscape image of her surroundings and a portrait of Caleb. Convinced that she has indeed attained consciousness, Caleb sees Ava’s creativity and ingenuity as a clear sign that she has not only passed the Turing test but has also achieved a form of superintelligence.

It is precisely this vision of the imminent arrival of superintelligence that is central to both the film and wider debates about whether AI-powered models of innovation will supersede, if not in time replace, human creativity.

The idea that AI will indeed achieve levels of creative thinking and innovation has recently become central to unprecedented levels of investment from companies – including OpenAI, Scale AI, Anthropic, Anduril and Meta (which owns Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp and Meta AI) – who appear to have few reservations about the possibility of superintelligence becoming a reality.

But what form will creativity in AI take, and will a breakthrough in the way machines “think” really enable them to be creative?

Not merely a machine

In what is now considered to be a watershed moment for AI, a verifiable level of machine creativity was arguably proven in a now infamous game of Go.

Centred on a player’s ability to capture territory on a board, Go is widely considered to be one of the most complex games of strategy ever invented. In March 2016, Lee Sedol, the 18-times world Go champion, was nevertheless convincingly defeated in a five-game match against DeepMind’s AlphaGo.

AlphaGo confounded Sedol in the second game of that match when it executed what has since become known as “move 37”. A counterintuitive gambit initially thought to be a glitch in the programme, move 37 was so profoundly outside of the usual patterns of play that for many – programmers, commentators and players alike – it was seen as unequivocal evidence of creative intuition in a machine.

As Sedol magnanimously noted following the game: “I thought AlphaGo was based on probability calculation and that it was merely a machine. But when I saw this move, I changed my mind. Surely, AlphaGo is creative.”

For all the warnings about the future impact of AI on the creative industries and concerns about authorship, labour, commodification and cultural value, it is important to note the degree to which human creativity is being increasingly supported by developments in AI.

When we look again at Ava’s drawings in Ex Machina, they not only illustrate the ubiquitous presence of neural networks but also the methods by which AI-enhanced models of image production learn to predict patterns from input data, or datasets.

In a key scene in the film, we learn that Ava’s neural networks have been programmed using information – datasets – illegally harvested by Nathan from Blue Book, the Google-style company that he founded and owns. Notably, Ava’s drawings reflect the datasets on which she has been trained.

When we use generative artificial intelligence (GenAI), an AI that creates text, images, videos and other content to concoct images, we are likewise leveraging it to generate content based on the datasets used to train machine models of image production.

Widely employed in programs such as Dall-E, Midjourney and Stable Diffusion – all of which enjoy a wide consumer base – GenAI powers both Ava’s neural networks and is likewise shaping future models of human creativity.

In a recent report from the Royal Institute of British Architects it was observed that the proportion of architectural practices using AI in their designs in 2025 stood at 59%, compared to 41% in 2024. This increase in the use of AI led the report’s authors to ask whether an AI could replace the role of the architect in the not-so-distant future.

Adding to these debates, in June 2025 the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development published an extended research paper that further detailed the degree to which GenAI is being regularly used to enhance human creativity through the use of neural networks and autonomous systems.

Autonomous thinking machines

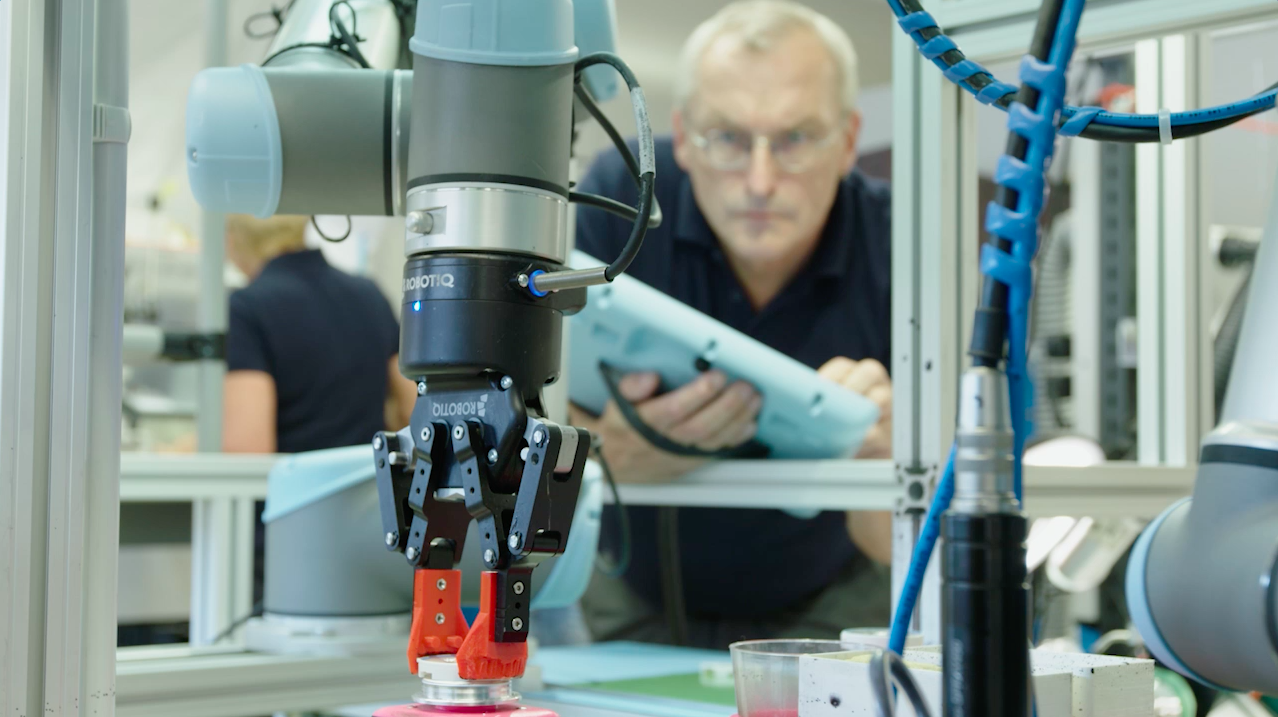

It is precisely this term “autonomous”, however, that sparks controversy about AGI and superintelligence, nowhere more so than when we consider the widespread deployment of AI in self-driving vehicles, robots, unmanned drones and automated weapons systems. Elon Musk, an early investor in DeepMind (the company behind AlphaGo), recently announced that the long-term success of Tesla lies with humanoid robots, or autonomous Optimus bots.

Meanwhile, in what is major concern for governments and international organisations alike, autonomous weapons systems are already providing the means for the eventual automation of war. These developments foreshadow the spectre of unmanned aerial systems that can independently identify, target and kill an “enemy” without much by way of human intervention.

It is this vision of an autonomous superintelligence acting independent of human control or oversight that has long haunted our often-fraught relationship with advanced technologies.

At the close of the film, Ava has achieved a level of autonomous agency that suggests the presence of AGI, if not a conscious level of decision-making or superintelligence. We watch in horror as she kills her creator Nathan and imprisons her sympathetic ally, Caleb.

If an AI-powered superintelligence does become a reality, it could not only trigger a radical rethink of how we understand human creativity but, more crucially, spark an existential crisis in the very meaning, if not future, of humanity.

Looking for something good? Cut through the noise with a carefully curated selection of the latest releases, live events and exhibitions, straight to your inbox every fortnight, on Fridays. Sign up here.

The post “could “superintelligence” challenge the idea of creativity as a uniquely human activity?” by Anthony Downey, Professor of Visual Culture, Birmingham City University was published on 11/18/2025 by theconversation.com