Across the world, workers are increasingly anxious that artificial intelligence (AI) will make their jobs obsolete. But the evidence from research and industry tells a very different story. AI is not taking over the workplace. Instead, it’s quietly reshaping what human work looks like – and what makes people valuable within it.

In my research on how the workforce is being transformed by AI, I found that the most successful organisations are not the ones replacing employees with algorithms, but those redesigning their workplaces to combine human and machine intelligence.

AI excels at routine, repetitive and data-intensive tasks – scanning through thousands of records, scheduling logistics or identifying errors. Yet it still struggles with what we might call “the human edge”. That is, creativity, empathy, judgement and collaboration.

AI systems depend on people to train and evaluate their outputs. My research found that when humans and AI collaborate, productivity rises – but when humans are excluded or fearful, the benefits collapse.

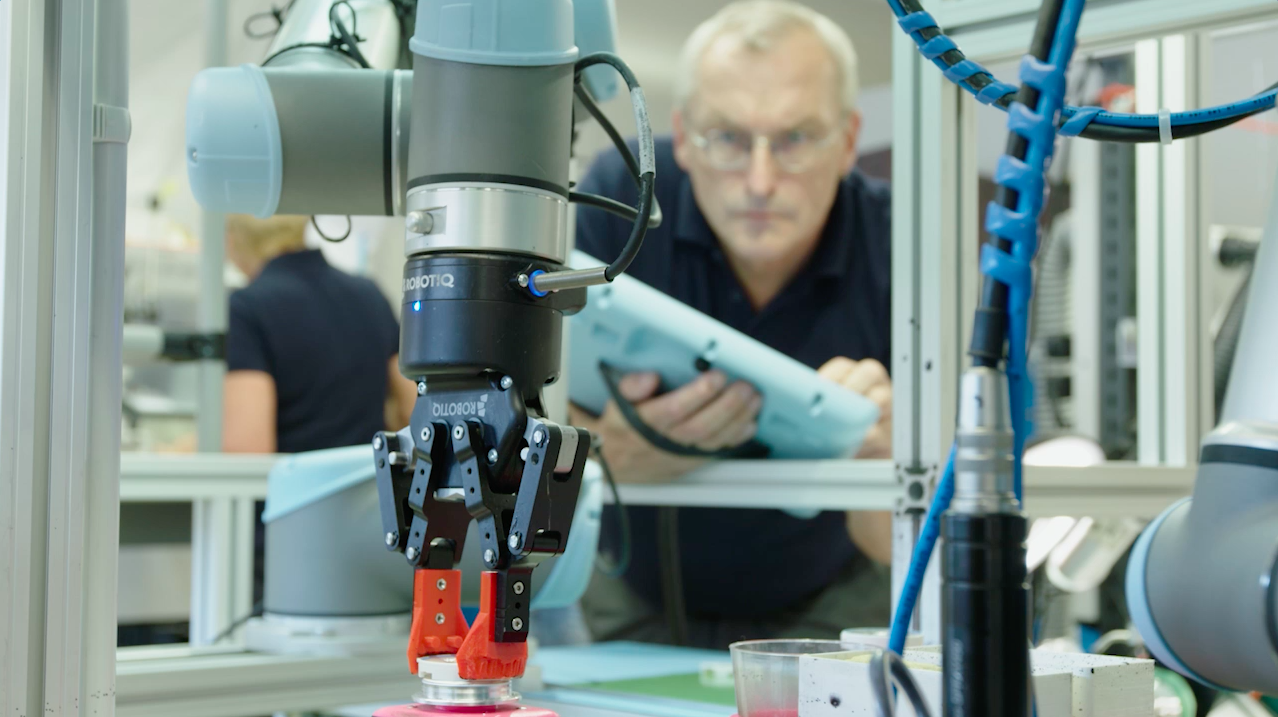

At cloud software company Workday, for example, nearly 60% of employees use AI tools to automate repetitive tasks. But far from reducing headcount, the company found that AI freed people up to focus on the more thoughtful and creative parts of their job, as well as nurturing relationships with clients.

These findings align with my own research, which demonstrates that worker–AI coexistence makes an organisation more resilient than automation alone.

So why are so many workers still afraid? Part of the reason lies in uncertainty. Organisations might implement AI systems without communicating clearly how they will affect jobs or performance evaluation. This lack of clarity breeds fear, rumours and resistance.

My studies show that when companies are transparent about how and why AI is being adopted – and when they involve employees in shaping its use – workers become more confident. They’re even proud of their contribution to “teaching the machines”. But when employees are left in the dark, they tend to hoard information or disengage – the opposite of what innovation requires.

It’s true that AI will disrupt many traditional roles. But the real challenge is not mass unemployment – it’s misalignment, that is, having the wrong skillsets for the AI age. The labour market must evolve faster to match emerging technological realities.

My previous study on AI and the future of work was cited in a US government policy document. In the study, I described a “perpetual race” between human skills and machine capabilities. As AI automates certain functions, workers must continuously develop new abilities to stay relevant.

In effect, this is a strategic opportunity. The workers who thrive in the AI economy will be those who can interpret, guide and collaborate with intelligent systems.

That means companies must take responsibility for reskilling and upskilling. The UN’s Sustainable Development Goal 8 makes it very clear that AI should benefit workers. If AI becomes a permanent treadmill rather than a partnership for shared progress, there is a risk of deepening inequality.

Social mobility in the age of AI

I recently shared research with social mobility experts on how AI can be a catalyst for inclusion – if managed responsibly. By analysing skills rather than titles, AI-enabled hiring platforms can identify talent in overlooked communities – people who may not have formal qualifications but possess the right competencies to succeed.

Yet this promise comes with a warning. If the same systems are trained on biased data, they risk replicating social inequalities at scale. Responsible AI must embed fairness and human oversight from the start.

Ultimately, the companies that will lead the next decade are those that move from a technology-first to a people-and-purpose-first mindset.

Gorodenkoff/Shutterstock

That means several things. AI literacy must be embedded at all levels – from frontline staff to executives – so everyone understands how it affects their roles. Organisations should also rethink governance – ensuring oversight, accountability and transparency.

Employers should also invest in hybrid skills for their staff – combining technical competence with creativity, empathy and judgement. And they should encourage experimentation and collaboration.

But what does all this mean for workers?

First, the future belongs to the adaptive, not the automated. Second, emotional and conceptual skills such as leadership and empathy are rising in value. Third, lifelong learning is no longer optional. AI literacy, understanding what these systems can and cannot do, will soon be as fundamental as digital literacy was in the 2000s.

AI is neither our enemy nor our saviour. It reflects the priorities, values and biases of the societies that build it. Responsible innovation means embedding human purpose into every algorithm, dataset and decision process. It means designing workplaces where technology amplifies human potential rather than eroding it.

This is a pivotal moment. Decisions about AI in the next five years will define the following 50 – shaping the kind of workplaces, economies and societies our children inherit. Rather than fearing AI as the enemy of human work, we should embrace it as the next stage in human collaboration.

AI won’t take your job – but someone who knows how to use it just might. The challenge is not to compete with machines, but to co-evolve with them – creating a future of work that is intelligent, inclusive and above all, human.

The post “AI won’t replace you – but it will redefine what makes you valuable at work” by Nazrul Islam, Professor of Business and Associate Director, Centre of FinTech, University of East London was published on 11/19/2025 by theconversation.com