After January’s Southern California wildfires, the question of burying energy infrastructure to prevent future fires has gained renewed urgency in the state. While the exact cause of the fires remains under investigation, California utilities have spent years undergrounding power lines to mitigate fire risks. Pacific Gas & Electric, which has installed over 1,287 kilometers of underground power lines since 2021, estimates the method is 98 percent effective in reducing ignition threats. Southern California Edison has buried over 40 percent of its high-risk distribution lines, and 63 percent of San Diego Gas & Electric’s regional distribution system is now underground.

Still, the exorbitant cost of underground construction leaves much of the U.S. power grid’s 8.8 million kilometers of distribution lines and 180 million utility poles exposed to tree strikes, flying debris, and other opportunities for sparks to cascade into a multi-acre blaze. Recognizing the need for cost-effective undergrounding solutions, the U.S. Department of Energy launched GOPHURRS in January 2024. The three-year program pours $34 million into 12 projects to develop more efficient undergrounding technologies that minimize surface disruptions while supporting medium-voltage power lines.

One recipient, Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio, is building a self-propelled robotic sleeve that mimics earthworms’ characteristic peristaltic movement to advance through soil. Awarded $2 million, Case’s “peristaltic conduit” concept hopes to more precisely navigate underground and reduce the risk of unintended damage, such as breaking an existing pipe.

Why Is Undergrounding So Expensive?

Despite its benefits, undergrounding remains cost-prohibitive at US $1.1 to $3.7 million per kilometer ($1.8 to $6 million per mile) for distribution lines and $3.7 to $62 million per kilometer for transmission lines, according to estimates from California’s three largest utilities. That’s significantly more than overhead infrastructure, which costs $394,000 to $472,000 per kilometer for distribution lines and $621,000 to $6.83 million per kilometer for transmission lines.

The most popular method of undergrounding power lines, called open trenching, requires extensive excavation, conduit installation, and backfilling, making it expensive and logistically complicated. And it’s often impractical in dense urban areas where underground infrastructure is already congested with plumbing, fiber optics, and other utilities.

Trenchless methods like horizontal directional drilling (HDD) provide a less invasive way to get power lines under roads and railways by creating a controlled, curved bore path that starts at a shallow entry angle, deepens to pass obstacles, and resurfaces at a precise exit point. But HDD is even more expensive than open trenching due to specialized equipment, complex workflows, and the risk of damaging existing infrastructure.

Given the steep costs, utilities often prioritize cheaper fire mitigation strategies like trimming back nearby trees and other plants, using insulated conductors, and stepping up routine inspections and repairs. While not as effective as undergrounding, these measures have been the go-to option, largely because faster, cheaper underground construction methods don’t yet exist.

Ted Kury, director of energy studies at the University of Florida’s Public Utility Research Center, who has extensively studied the costs and benefits of undergrounding, says technologies implementing directional drilling improvements “could make undergrounding more practical in urban or densely populated areas where open trenching, and its attendant disruptions to the surrounding infrastructure, could result in untenable costs.”

Earthworm-Inspired Robotics for Power Lines

In Case’s worm-inspired robot, alternating sections are designed to expand and retract to anchor and advance the machine. This flexible force increases precision and reduces the risk of impacting and breaking pipes. Conventional methods require large turning radii exceeding 300 meters, but Case’s 1.5-meter turning radius will enable the device to flexibly maneuver around existing infrastructure.

“We use actuators to change the length and diameter of each segment,” says Kathryn Daltorio, an associate engineering professor and co-director of Case’s Biologically-Inspired Robotics Lab. “The short and fat segments press against the walls of the burrow, then they anchor so the thin segments can advance forward. If two segments aren’t touching the ground but they’re changing length at the same time, your anchors don’t slip and you advance forward.”

Daltorio and her colleagues have studied earthworm-inspired robotics for over a decade, originally envisioning the technology for surgical and confined-space applications before recognizing its potential for undergrounding power lines.

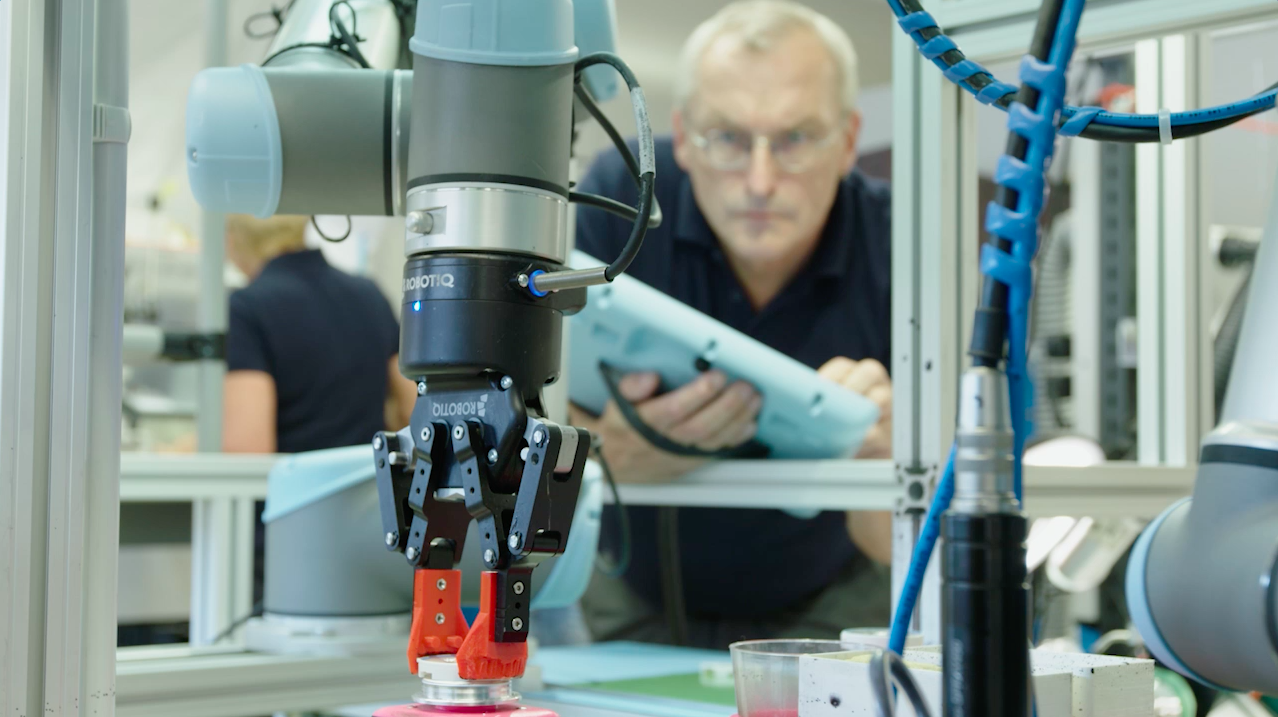

Case Western Reserve University’s worm-like digging robot can turn faster than other drilling techniques to avoid obstacles.Kathryn Daltorio/Case School of Engineering

Traditional HDD relies on pushing a drill head through soil, requiring more force as the bore length grows. Case’s drilling concept generates the force needed for the tip from the peristaltic segments within the borehole. As the path gets longer, only the front segments dig deeper. “If the robot hits something, operators can pull back and change directions, burrowing along the way to complete the circuit by changing the depth,” Daltorio says.

Another key difference from HDD is integrated conduit installation. In HDD, the drill goes through the entire length first, and then the power conduit is pulled through. Case’s peristaltic robot lays the conduit while traveling, reducing the overall installation time.

Advancements in Burrowing Precision

“The peristaltic conduit approach is fascinating [and] certainly seems to be addressing concerns regarding the sheer variety of underground obstacles,” says the University of Florida’s Kury. However, he highlights a larger concern with undergrounding innovations—not just Case’s—in meeting a constantly evolving environment. Today’s underground will look very different in 10 years, as soil profiles shift, trees grow, animals tunnel, and people dig and build. “Underground cables will live for decades, and the sustainability of these technologies depends on how they adapt to this changing structure,” Kury added.

Daltorio notes that current undergrounding practices involve pouring concrete around the lines before backfilling to protect them from future excavation, a challenge for existing trenchless methods. But Case’s project brings two major benefits. First, by better understanding borehole design, engineers have more flexibility in choosing conduit materials to match the standards for particular environments. Also, advancements in burrowing precision could minimize the likelihood of future disruptions from human activities.

The research team is exploring different ways to reinforce the digging robot’s exterior while it’s underground.Olivia Gatchall

Daltorio’s team is collaborating with several partners, with Auburn University in Alabama contributing geotechnical expertise, Stony Brook University in New York running the modeling, and the University of Texas at Austin studying sediment interactions.

The project aims to halve undergrounding costs, though Daltorio cautions that it’s too early to commit to a specific cost model. Still, the time-saving potential appears promising. “With conventional approaches, planning, permitting and scheduling can take months,” Daltorio says. “By simplifying the process, it might be a few inspections at the endpoints, a few days of autonomous burrowing with minimal disruption to traffic above, followed by a few days of cleaning, splicing, and inspection.”

The post “Worm-like Robots Install Power Lines Underground” by Shannon Cuthrell was published on 03/10/2025 by spectrum.ieee.org