News that Dutch publishing house Veen Bosch & Keuning (VBK) has confirmed plans to experiment using AI to translate fiction has stirred up a thought-provoking debate. Some believe it marks the beginning of the end for human translators, while others see this as the opening up of a new world of possibilities to bring more literature to even more people. These arguments are becoming increasingly vocal as the advance of AI accelerates at an ever-increasing rate.

This debate interests me as my work examines the intersections of art, ethics, technology and culture, and I have published research in areas of emerging technologies, particularly in relation to human enhancement.

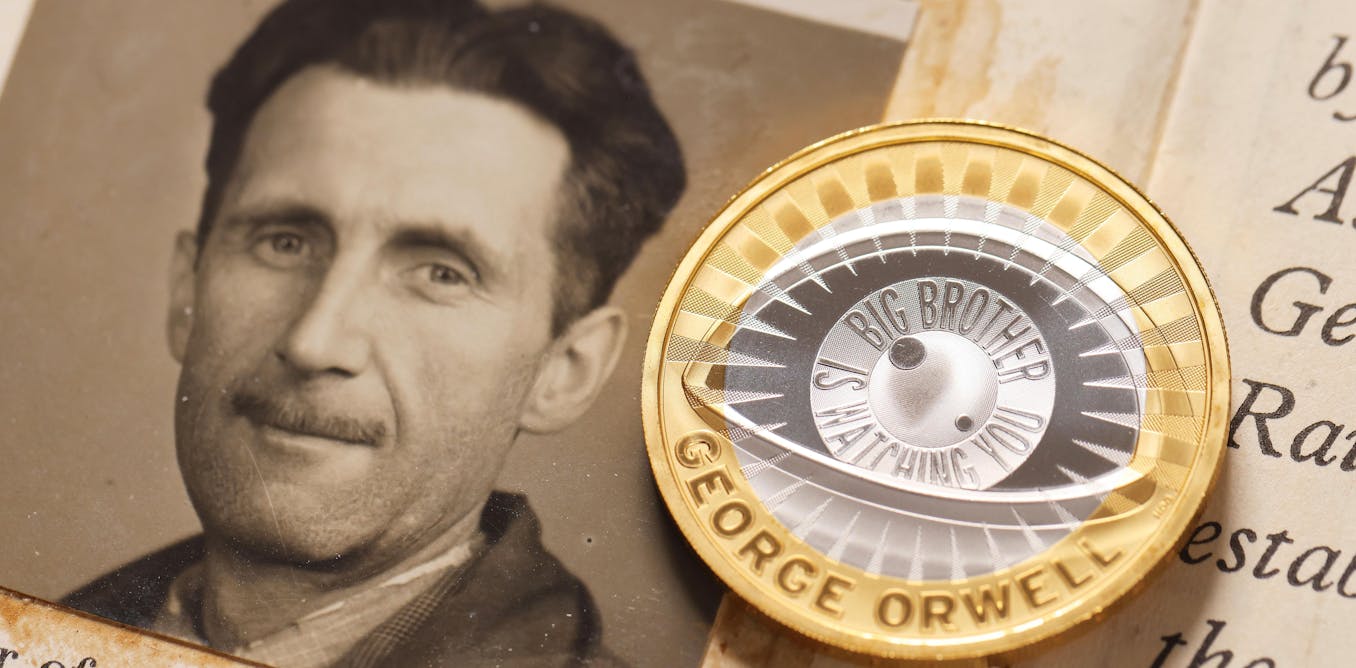

Across every new technology, debate centres on what we stand to lose by embracing change and, with AI, this echoes the developments in the recent history of genetic science. But somehow, when we meddle with culture and human history, it can seem that something even more fundamental than DNA is at stake.

Fiction translation, with its intricate language, emotional undertones and nuances, has traditionally been the domain of skilled human translators. But this initiative to use AI in fiction translation may be an early foray into disrupting what is often considered the last bastion of humanity’s most remarkable – and perhaps irreplaceable – achievement: the ability to express complex human sentiments through words.

As such, the decision to use AI to translate books raises an important question that speaks to the core of our concerns about how AI could take precedence over human endeavour: can a machine capture the nuances that give fiction its depth, or is it simply too complex for an algorithm?

In defence of the human, language – especially in literature – isn’t just about words. It’s about cultural context, subtext and the distinct voice of the writer. As such, only a human who understands both languages and cultures could accurately translate the heart of a story without losing its essence.

Yet machine learning has made extraordinary strides in understanding language, best evidenced by the latest version of ChatGPT, which includes an audio conversational agent.

We seem to be at a point in the development of AI where its capabilities in using language adequately approximate human functionality in a wide range of circumstances, from customer service chatbots, to a growing number of health diagnostic tools. Even the World Health Organization has created and deployed an AI “health worker” using a conversational platform.

Looking for something good? Cut through the noise with a carefully curated selection of the latest releases, live events and exhibitions, straight to your inbox every fortnight, on Fridays. Sign up here.

Of course, it’s also true that human translators, despite their expertise, sometimes miss nuances or make errors. And there’s an enduring belief among scholars and literary purists that to truly understand an author’s intent, one must read them in the original language.

Learning every language to read every book is, of course, impractical. But not understanding a particular language can exclude us from discovering great works of native literature that may never be translated into our own languages. For this reason, we might advance a social justice argument for using AI translation to radically expand access to insights from many cultures and their varied languages. On this basis, AI translation is more morally problematic to withhold than to allow.

This is where AI translation holds promise: expanding access to literature for those who might otherwise never have the chance to engage with it.

The potential here is vast. Only a small fraction of the world’s literature is ever translated. If AI could increase that, then it would broaden access to diverse voices and ideas, enriching the global literary landscape. And for works that might never find a human translator due to cost, language or niche appeal, AI could be the only viable way to bring works to new audiences.

Of course, the rise of AI in translation is not without its downsides. If AI replaces human translators, we risk losing not only their craft but also their insights and the cultural understanding they bring. And while it’s easy to argue that AI should only be used for works that wouldn’t otherwise be translated, it could still undermine the economic viability of human translation, further reducing demand for human translators.

But it doesn’t have to be an either/or scenario. AI could serve as a tool to augment, not replace, human translators. Translators could be involved in refining AI models, ensuring higher accuracy and quality, and curating works to be translated.

Imagine a world where translators and AI work together, pushing the boundaries of what can be accomplished. If AI can help translate more books, the collaboration could lead to more inclusive access to global literature, enhancing our collective understanding of diverse cultures.

In the long run, if AI brings us closer to a world where every book in every language is accessible to every one, then it’s an extraordinary vision worth embracing. What’s more, real-time translation is being used in some critical settings.

In one of my current projects my collaborator, the tech company MyManu, has already pioneered real-time translation earbuds, which are being used in some remarkable settings, such as helping asylum seekers understand and communicate more effectively, when arriving in a new country.

The path forward will require a balance: using AI to expand the reach of literature, while preserving and valuing the irreplaceable artistry of human translators. But increasingly it looks like we’re only scratching the surface of the vast possibilities afforded by this new technology.

The post “how AI could assist humans in expanding access to global literature and culture” by Andy Miah, Chair in Science Communication & Future Media, University of Salford was published on 01/08/2025 by theconversation.com