For four years, we’ve been teaching a class on music and the mind. We’ve asked the students at the start of each semester to complete a short, informal survey on their music education and favorite songs and artists.

Our students’ musical education backgrounds always range from none to more than a decade of lessons and ensembles. But we’ve watched the list of favorite songs and artists get longer and more varied each year. When we ask the entire group about certain songs, it is often the case that no one, save for the person who included it, has heard it.

The findings from these informal classroom surveys are consistent with recent research showing diverse and eclectic musical preferences among adolescents. In a study on the listening habits of Los Angeles middle school students, we found that they appreciate artists representing a range of genres, from the K-pop supergroup BTS to the heavy metal band System of a Down to Beethoven.

But what happens when, as we’ve observed, young people don’t know what their peers are listening to? And does it matter that teens aren’t necessarily choosing the music they’re using to understand themselves and the world, let alone that no humans are selecting songs they’re exposed to?

A shared soundscape goes private

For centuries, the only way to experience music was to see it live – at small, private performances, in community gatherings or in large concert halls.

Radios and record players transformed how people interacted with music. But because these devices were initially stationary, there was still a social element to listening. You might gather in a friend’s basement to hear hits on the radio, throw a listening party when a new album was released, make a mixtape for your beau or belt out a favorite song on the car radio with your best friend.

Introduced in 1979, the Sony Walkman marked another major turning point in how people listen to music. It became a lot easier for music to be a deeply private and personal experience – even more so with the introduction of the iPod and, later, smartphones.

H. Armstrong Roberts/ClassicStock via Getty Images

Listening to music this way isn’t always about what’s pulsing through your headphones. It can also cultivate agency: No matter where you are, you are your own DJ, controlling what gets played and when. And if you choose to keep it private, no one can hear it but you.

Particularly for adolescents, this is a big deal. It creates a protective bubble that may counteract a lack of personal space at school or at home.

Young people listen to a lot of music throughout the day, whether it’s while doing homework, training for sports, eating or even sleeping. There’s an element of mood regulation at play: Songs can divert unpleasant emotions or elicit positive ones, and also encourage reflection during difficult experiences.

I got ‘algo-rhythm’

Making a playlist used to mean playing tapes and recording individual songs onto another tape, or waiting for the radio to play a song, hitting “record” on your cassette player to capture it, song by song, until you had a mixtape of your favorite tunes.

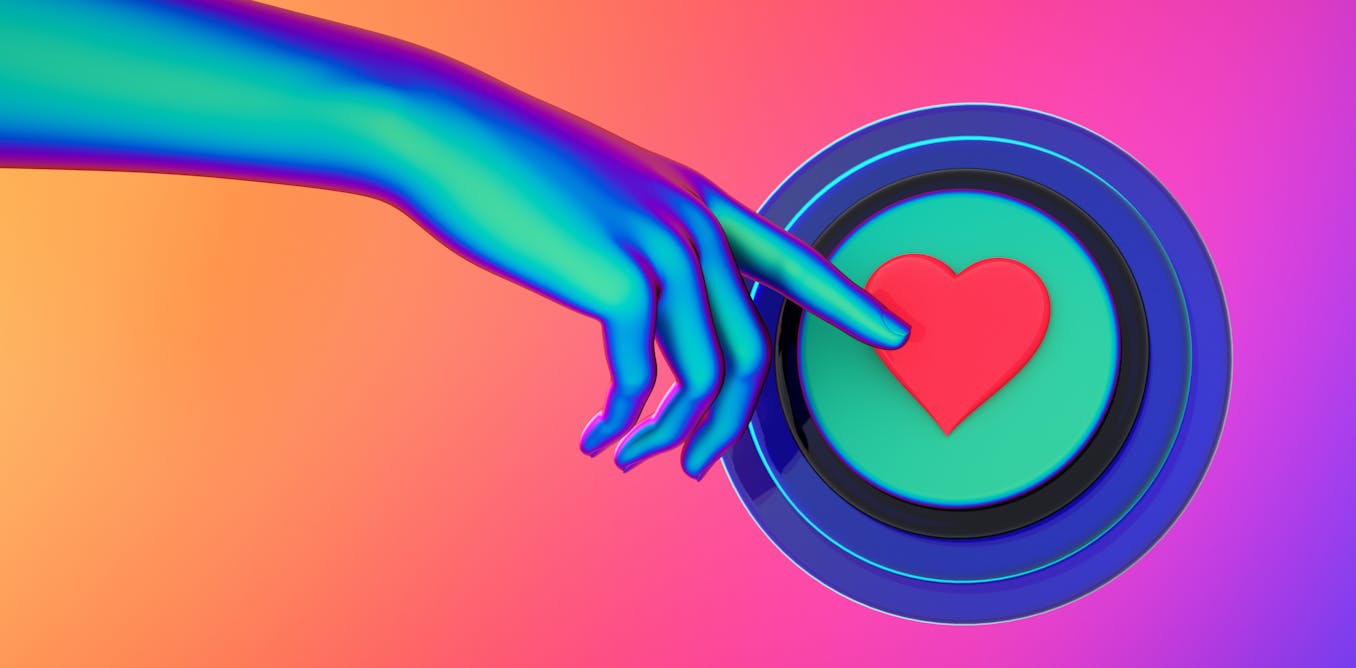

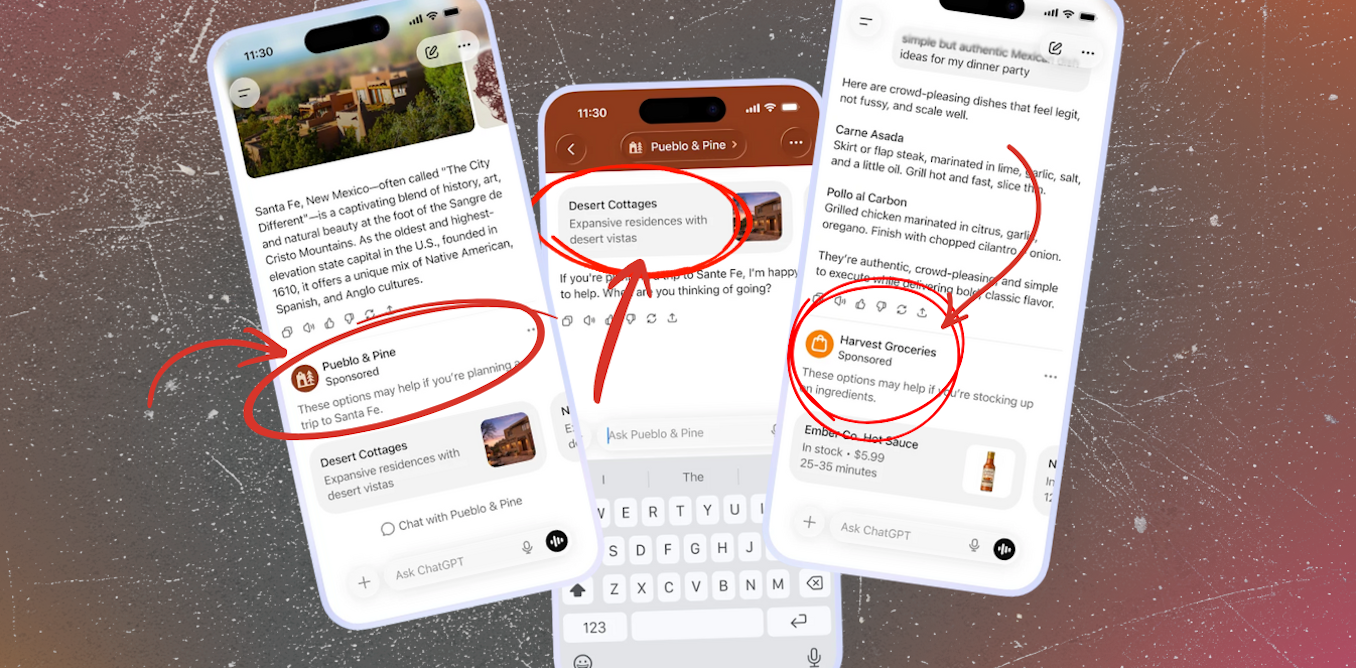

Now, listening often happens via streaming, where artificial intelligence and social media platforms team up to suggest playlists for you.

While you explore and share music on social media, AI tracks the activity and compares it to data from other listeners; in this way, it hones its predictions about what you might like to hear in the future.

AI is being put to work to know not only what a user wants to hear, but also to predict the next big hit that everyone will listen to. Until recently, AI’s power for predicting hits relied largely on song characteristics like bounciness, positiveness and danceability, and hovered at around 50% accuracy.

Other studies have analyzed physiological responses to music, like heart rate, which can be gleaned from the biodata on teen’s smartwatches, to predict top hits.

These studies add to existing concerns about the mining of personal information and data, and there have long been fears that AI can’t be trusted and will end up manipulating people. When it comes to the way AI influences your listening habits, you might wonder whether you like a song because you truly like it, or whether you only enjoy it because AI has fed you enough similar songs that familiarity has bred appreciation.

Some listeners feel that algorithmic curation causes them to be stuck in a listening rut. Their playlists are populated with songs and artists they’ve never heard of before, yet they all sound eerily similar.

The upside to AI

In the past, being in a listening rut was something a teenager may not have even noticed.

Exposed to a steady diet of the same songs regularly playing on the radio – and later, on MTV and VH1 – adolescents’ musical consumption was dominated by the “Top-40” artists. Their palettes were sculpted by a widely shared, if perhaps narrow, repertoire of musical knowledge.

KMazur/WireImage via Getty Images

AI-generated playlists have disrupted this, and the two of us don’t see that as necessarily a bad thing. A stunning range of music is available to young people, and no longer do radio DJs, ratings and record companies serve as gatekeepers.

Spotify currently lists thousands of genres and creates more each year so that, as the company explains, they are more “recognizable, representative, and holistic to our listeners and communities.”

Like receiving a cherished gift you never knew you wanted, young people can be exposed to great music – with its accompanying cultural traditions – that they would be less likely to have discovered on their own, whether it’s Indian pop music, Japanese rock or Afro-juju, a style of Nigerian popular music.

If teens think their AI-influenced playlists are dull, they still have the ability to search for new music. Just because algorithms and AI can suggest songs, it doesn’t preclude listeners from researching and discovering music on their own, or sharing playlists with friends and relatives.

Anything that exists, they can find. The store is always open.

Identity, community and music

Back to our college class: We noticed little overlap among the students. But instead of consuming only from a menu of industry megastars, our students showed a willingness to listen to a variety of genres and subgenres that AI will offer up.

When asked to reveal the most recent song or piece that they had listened to on a specific week, 6% had listened to R&B singer SZA, 2% to singer Renée Rapp, 2% to pop sensation Taylor Swift and 2% to pop rockers The 1975.

The remaining 80-plus selections featured a panoply of genres: computer music, rock, pop, rap, country, reggaeton, film music, heavy metal, indie and Latin ballads.

As young people transition from childhood to adulthood, two seemingly opposing processes become paramount: forming a unique identity, while at the same time becoming part of a community. Music listening and preferences play an important role in this process.

AI-generated playlists have the potential to challenge this transition.

So does AI make it easier to differentiate the self, but harder to bond with others? Or does it, instead, offer a broader spectrum for self-exploration and communal connection?

The truth is, no one really knows.

Fears of new technologies are commonplace. For example, as scheduled network TV fell out of favor, a lot of common ground for discussion and connection disappeared with it. Will 50 million Americans ever again tune in to watch the series finale of a sitcom, as they did for “Friends” in 2004?

If AI is, indeed, contributing to the transformation of adolescents’ communal listening experiences, then AI playlists are more than just a convenient way to discover your next workout tune. They are a revolution worth paying attention to.

The post “How AI is shaping the music listening habits of Gen Z” by Beatriz Ilari, Professor of Music Teaching and Learning, University of Southern California was published on 03/13/2024 by theconversation.com