As the International Olympic Committee (IOC) embraces AI-assisted judging, this technology promises greater consistency and improved transparency. Yet research suggests that trust, legitimacy, and cultural values may matter just as much as technical accuracy.

The Olympic AI agenda

In 2024, the IOC unveiled its Olympic AI Agenda, positioning artificial intelligence as a central pillar of future Olympic Games. This vision was reinforced at the very first Olympic AI Forum, held in November 2025, where athletes, federations, technology partners, and policymakers discussed how AI could support judging, athlete preparation, and the fan experience.

At the 2026 Winter Olympics in Milano-Cortina, the IOC is considering using AI to support judging in figure skating (men’s and women’s singles and pairs), helping judges precisely identify the number of rotations completed during a jump. Its use will also extend to disciplines such as big air, halfpipe, and ski jumping (ski and snowboard events where athletes link jumps and aerial tricks), where automated systems could measure jump height and take-off angles. As these systems move from experimentation to operational use, it becomes essential to examine what could go right… or wrong.

Judged sports and human error

In Olympic sports such as gymnastics and figure skating, which rely on panels of human judges, AI is increasingly presented by international federations and sports governing bodies as a solution to problems of bias, inconsistency, and lack of transparency. Judging officials must assess complex movements performed in a fraction of a second, often from limited viewing angles, for several hours in a row. Post-competition reviews show that unintentional errors and discrepancies between judges are not exceptions.

This became tangible again in 2024, when a judging error involving US gymnast Jordan Chiles at the Paris Olympics sparked major controversy. In the floor final, Chiles initially received a score that placed her fourth. Her coach then filed an inquiry, arguing that a technical element had not been properly credited in the difficulty score. After review, her score was increased by 0.1 points, temporarily placing her in the bronze medal position. However, the Romanian delegation contested the decision, arguing that the US inquiry had been submitted too late – exceeding the one-minute window by four seconds. The episode highlighted the complexity of the rules, how difficult it can be for the public to follow the logic of judging decisions, and the fragility of trust in panels of human judges.

Moreover, fraud has also been observed: many still remember the figure skating judging scandal at the 2002 Salt Lake City Winter Olympics. After the pairs event, allegations emerged that a judge had favoured one duo in exchange for promised support in another competition – revealing vote-trading practices within the judging panel. It is precisely in response to such incidents that AI systems have been developed, notably by Fujitsu in collaboration with the International Gymnastics Federation.

What AI can (and cannot) fix in judging

Our research on AI-assisted judging in artistic gymnastics shows that the issue is not simply whether algorithms are more accurate than humans. Judging errors often stem from the limits of human perception, as well as the speed and complexity of elite performances – making AI appealing. However, our study involving judges, gymnasts, coaches, federations, technology providers, and fans highlights a series of tensions.

AI can be too exact, evaluating routines with a level of precision that exceeds what human bodies can realistically execute. For example, where a human judge visually assesses whether a position is properly held, an AI system can detect that a leg or arm angle deviates by just a few degrees from the ideal position, penalising an athlete for an imperfection invisible to the naked eye.

While AI is often presented as objective, new biases can emerge through the design and implementation of these systems. For instance, an algorithm trained mainly on male performances or dominant styles may unintentionally penalise certain body types.

In addition, AI struggles to account for artistic expression and emotions – elements considered central in sports such as gymnastics and figure skating. Finally, while AI promises greater consistency, maintaining it requires ongoing human oversight to adapt rules and systems as disciplines evolve.

Action sports follow a different logic

Our research shows that these concerns are even more pronounced in action sports such as snowboarding and freestyle skiing. Many of these disciplines were added to the Olympic programme to modernise the Games and attract a younger audience. Yet researchers warn that Olympic inclusion can accelerate commercialisation and standardisation, at the expense of creativity and the identity of these sports.

A defining moment dates back to 2006, when US snowboarder Lindsey Jacobellis lost Olympic gold after performing an acrobatic move – grabbing her board mid-air during a jump – while leading the snowboard cross final. The gesture, celebrated within her sport’s culture, eventually cost her the gold medal at the Olympics. The episode illustrates the tension between the expressive ethos of action sports and institutionalised evaluation.

AI judging trials at the X Games

AI-assisted judging adds new layers to this tension. Earlier research on halfpipe snowboarding had already shown how judging criteria can subtly reshape performance styles over time. Unlike other judged sports, action sports place particular value on style, flow, and risk-taking – elements that are especially difficult to formalise algorithmically.

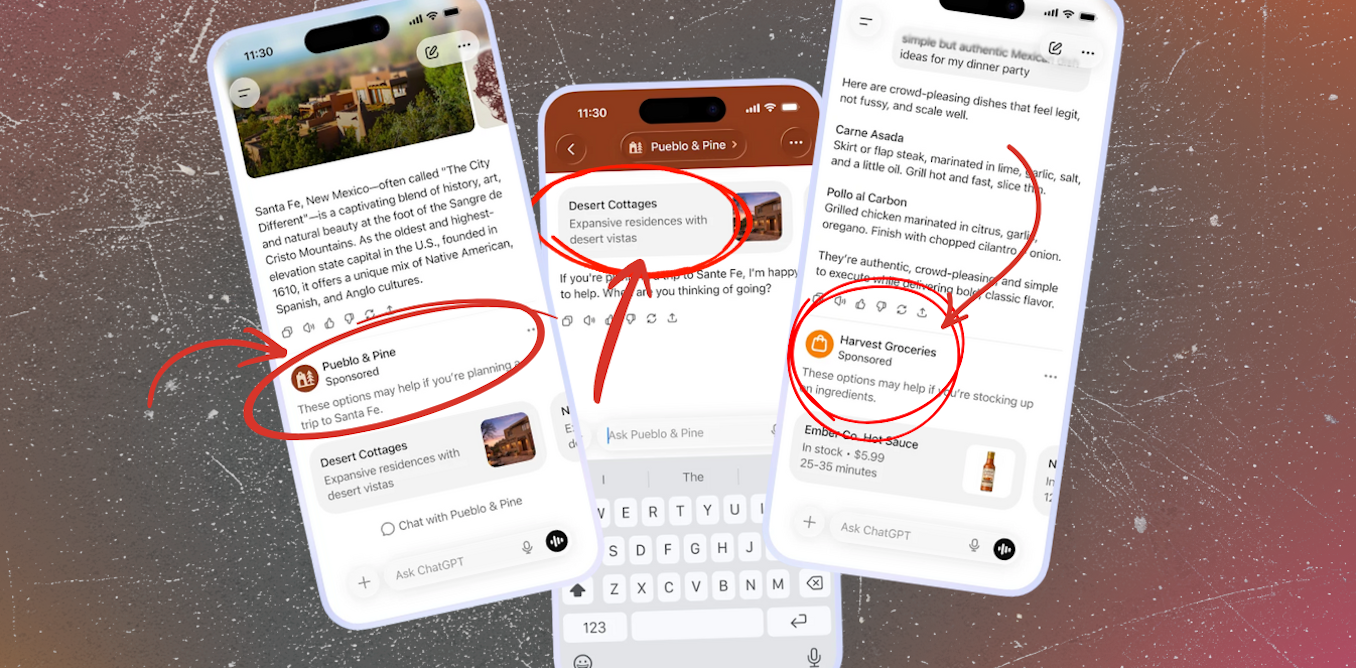

Yet AI was already tested at the 2025 X Games, notably during the snowboard SuperPipe competitions – a larger version of the halfpipe, with higher walls that enable bigger and more technical jumps. Video cameras tracked each athlete’s movements, while AI analysed the footage to generate an independent performance score. This system was tested alongside human judging, with judges continuing to award official results and medals. However, the trial did not affect official outcomes, and no public comparison has been released regarding how closely AI scores aligned with those of human judges.

Nonetheless, reactions were sharply divided: some welcomed greater consistency and transparency, while others warned that AI systems would not know what to do when an athlete introduces a new trick – something often highly valued by human judges and the crowd.

Beyond judging: training, performance and the fan experience

The influence of AI extends far beyond judging itself. In training, motion tracking and performance analytics increasingly shape technique development and injury prevention, influencing how athletes prepare for competition. At the same time, AI is transforming the fan experience through enhanced replays, biomechanical overlays, and real-time explanations of performances. These tools promise greater transparency, but they also frame how performances are understood – adding more “storytelling” “ around what can be measured, visualised, and compared.

At what cost?

The Olympic AI Agenda’s ambition is to make sport fairer, more transparent, and more engaging. Yet as AI becomes integrated into judging, training, and the fan experience, it also plays a quiet but powerful role in defining what counts as excellence. If elite judges are gradually replaced or sidelined, the effects could cascade downward – reshaping how lower-tier judges are trained, how athletes develop, and how sports evolve over time. The challenge facing Olympic sports is therefore not only technological; it is institutional and cultural: how can we prevent AI from hollowing out the values that give each sport its meaning?

A weekly e-mail in English featuring expertise from scholars and researchers. It provides an introduction to the diversity of research coming out of the continent and considers some of the key issues facing European countries. Get the newsletter!

The post “what makes it a game changer?” by Willem Standaert, Associate Professor, Université de Liège was published on 02/03/2026 by theconversation.com