Robots now see the world with an ease that once belonged only to science fiction. They can recognise objects, navigate cluttered spaces and sort thousands of parcels an hour. But ask a robot to touch something gently, safely or meaningfully, and the limits appear instantly.

As a researcher in soft robotics working on artificial skin and sensorised bodies, I’ve found that trying to give robots a sense of touch forces us to confront just how astonishingly sophisticated human touch really is.

My work began with the seemingly simple question of how robots might sense the world through their bodies. Develop tactile sensors, fully cover a machine with them, process the signals and, at first glance, you should get something like touch.

Except that human touch is nothing like a simple pressure map. Our skin contains several distinct types of mechanoreceptor, each tuned to different stimuli such as vibration, stretch or texture. Our spatial resolution is remarkably fine and, crucially, touch is active: we press, slide and adjust constantly, turning raw sensation into perception through dynamic interaction.

Engineers can sometimes mimic a fingertip-scale version of this, but reproducing it across an entire soft body, and giving a robot the ability to interpret this rich sensory flow, is a challenge of a completely different order.

Working on artificial skin also quickly reveals another insight: much of what we call “intelligence” doesn’t live solely in the brain. Biology offers striking examples – most famously, the octopus.

Octopuses distribute most of their neurons throughout their limbs. Studies of their motor behaviour show an octopus arm can generate and adapt movement patterns locally based on sensory input, with limited input from the brain.

Their soft, compliant bodies contribute directly to how they act in the world. And this kind of distributed, embodied intelligence, where behaviour emerges from the interplay of body, material and environment, is increasingly influential in robotics.

Touch also happens to be the first sense that humans develop in the womb. Developmental neuroscience shows tactile sensitivity emerging from around eight weeks of gestation, then spreading across the body during the second trimester. Long before sight or hearing function reliably, the foetus explores its surroundings through touch. This is thought to help shape how infants begin forming an understanding of weight, resistance and support – the basic physics of the world.

This distinction matters for robotics too. For decades, robots have relied heavily on cameras and lidars (a sensing method that uses pulses of light to measure distance) while avoiding physical contact. But we cannot expect machines to achieve human-level competence in the physical world if they rarely experience it through touch.

Simulation can teach a robot useful behaviour, but without real physical exploration, it risks merely deploying intelligence rather than developing it. To learn in the way humans do, robots need bodies that feel.

Intelligent bodies

One approach my group is exploring is giving robots a degree of “local intelligence” in their sensorised bodies. Humans benefit from the compliance of soft tissues: skin deforms in ways that increase grip, enhance friction and filter sensory signals before they even reach the brain. This is a form of intelligence embedded directly in the anatomy.

Research in soft robotics and morphological computation argues that the body can offload some of the brain’s workload. By building robots with soft structures and low-level processing, so they can adjust grip or posture based on tactile feedback without waiting for central commands, we hope to create machines that interact more safely and naturally with the physical world.

Perla Maiolino/Oxford Robotics Institute, CC BY-NC-SA

Healthcare is one area where this capability could make a profound difference. My group recently developed a robotic patient simulator for training occupational therapists (OTs). Students often practise on one another, which makes it difficult to learn the nuanced tactile skills involved in supporting someone safely. With real patients, trainees must balance functional and affective touch, respect personal boundaries and recognise subtle cues of pain or discomfort. Research on social and affective touch shows how important these cues are to human wellbeing.

To help trainees understand these interactions, our simulator, known as Mona, produces practical behavioural responses. For example, when an OT presses on a simulated pain point in the artificial skin, the robot reacts verbally and with a small physical “hitch” of the body to mimic discomfort.

Similarly, if the trainee tries to move a limb beyond what the simulated patient can tolerate, the robot tightens or resists, offering a realistic cue that the motion should stop. By capturing tactile interaction through artificial skin, our simulator provides feedback that has never previously been available in OT training.

Robots that care

In the future, robots with safe, sensitive bodies could help address growing pressures in social care. As populations age, many families suddenly find themselves lifting, repositioning or supporting relatives without formal training. “Care robots” would help with this, potentially meaning the family member could be cared for at home longer.

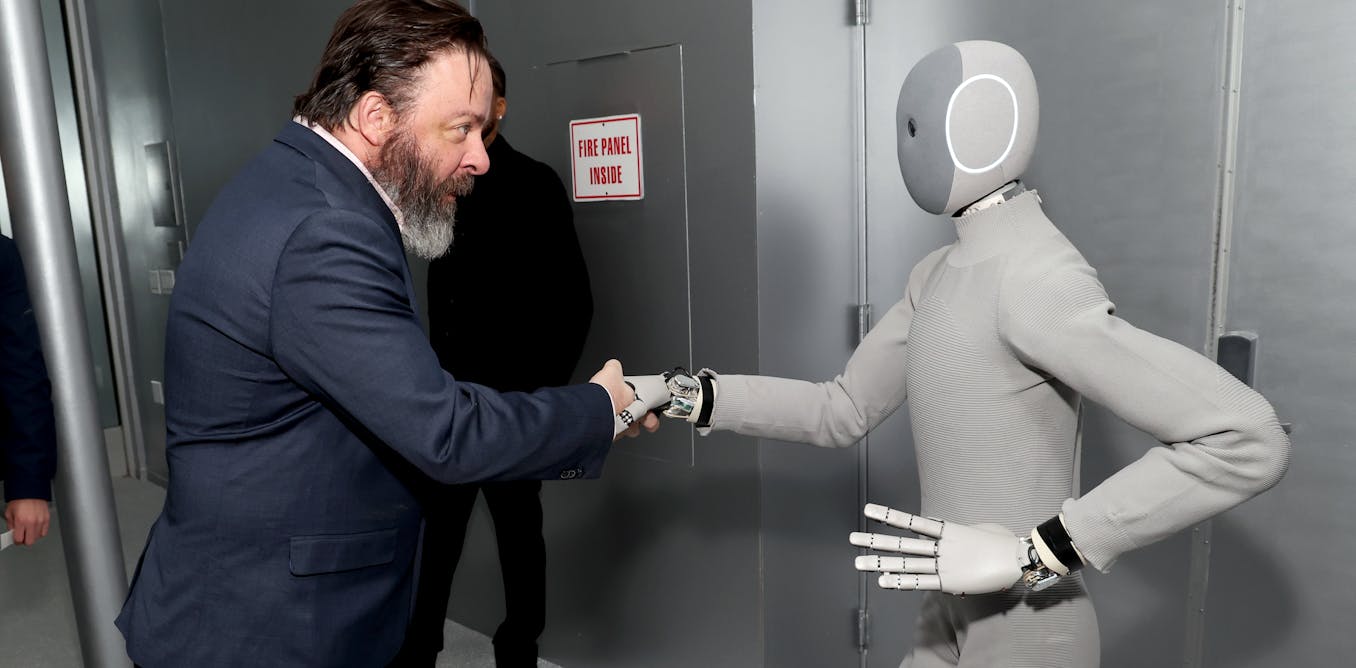

Surprisingly, progress in developing this type of robot has been much slower than early expectations suggested – even in Japan, which introduced some of the first care robot prototypes. One of the most advanced examples is Airec, a humanoid robot developed as part of the Japanese government’s Moonshot programme to assist in nursing and elderly-care tasks. This multifaceted programme, launched in 2019, seeks “ambitious R&D based on daring ideas” in order to build a “society in which human beings can be free from limitations of body, brain, space and time by 2050”.

Throughout the world, though, translating research prototypes into regulated robots remains difficult. High development costs, strict safety requirements, and the absence of a clear commercial market have all slowed progress. But while the technical and regulatory barriers are substantial, they are steadily being addressed.

Robots that can safely share close physical space with people need to feel and modulate how they touch anything that comes into contact with their bodies. This whole-body sensitivity is what will distinguish the next generation of soft robots from today’s rigid machines.

We are still far from robots that can handle these intimate tasks independently. But building touch-enabled machines is already reshaping our understanding of touch. Every step toward robotic tactile intelligence highlights the extraordinary sophistication of our own bodies – and the deep connection between sensation, movement and what we call intelligence.

This article was commissioned in conjunction with the Professors’ Programme, part of Prototypes for Humanity, a global initiative that showcases and accelerates academic innovation to solve social and environmental challenges. The Conversation is the media partner of Prototypes for Humanity 2025.

The post “The science of human touch – and why it’s so hard to replicate in robots” by Perla Maiolino, Associate Professor of Engineering Science, member of the Oxford Robotics Institute, University of Oxford was published on 12/10/2025 by theconversation.com