It seems the AI hype has turned into an AI bubble. There have been many bubbles before, from the Tulip mania of the 17th century to the derivatives bubble of the 21st century. For many commentators, the most relevant precedent today is the dotcom bubble of the 1990s. Back then, a new technology (the World Wide Web) unleashed a wave of “irrational exuberance”. Investors poured billions into any company with “.com” in the name.

Three decades later, another new technology has unleashed another wave of exuberance. Investors are pouring billions into any company with “AI” in its name. But there is a crucial difference between these two bubbles, which isn’t always recognised. The World Wide Web existed. It was real. General Artificial Intelligence does not exist, and no one knows if or when it ever will.

In February, the CEO of OpenAI, Sam Altman, wrote on his blog that the very latest systems have only just started to “point towards” AI in its “general” sense. OpenAI may market its products as “AIs”, but they are merely statistical data-crunchers, rather than “intelligences” in the sense that human beings are intelligent.

So why are investors so keen to give money to the people selling AI systems? One reason might be that AI is a mythical technology. I don’t mean it is a lie. I mean it evokes a powerful, foundational story of Western culture about human powers of creation.

Perhaps investors are willing to believe AI is just around the corner because it taps into myths that are deeply ingrained in their imaginations?

The myth of Prometheus

The most relevant myth for AI is the Ancient Greek myth of Prometheus.

There are many versions of this myth, but the most famous are found in Hesiod’s poems Theogony and Works and Days, and in the play Prometheus Bound, traditionally attributed to Aeschylus.

Prometheus was a Titan, a god in the Ancient Greek pantheon. He was also a criminal who stole fire from Hephaestus, the blacksmith god. Hiding the fire in a stalk of fennel, Prometheus came to earth and gave it to humankind. As punishment, he was chained to a mountain, where an eagle visited every day to eat his liver.

Prometheus’ gift was not simply the gift of fire; it was the gift of intelligence. In Prometheus Bound, he declares that before his gift humans saw without seeing and heard without hearing. After his gift, humans could write, build houses, read the stars, perform mathematics, domesticate animals, construct ships, invent medicines, interpret dreams and give proper offerings to the gods.

The myth of Prometheus is a creation story with a difference. In the Hebrew Bible, God does not give Adam the power to create life. But Prometheus gives (some of) the gods’ creative power to humankind.

Hesiod indicates this aspect of the myth in Theogony. In that poem, Zeus not only punishes Prometheus for the theft of fire; he punishes humankind as well. He orders Hephaestus to fire up his forge and construct the first woman, Pandora, who unleashes evil on the world.

The fire that Hephaestus uses to make Pandora is the same fire that Prometheus has given humankind.

Wikimedia Commons

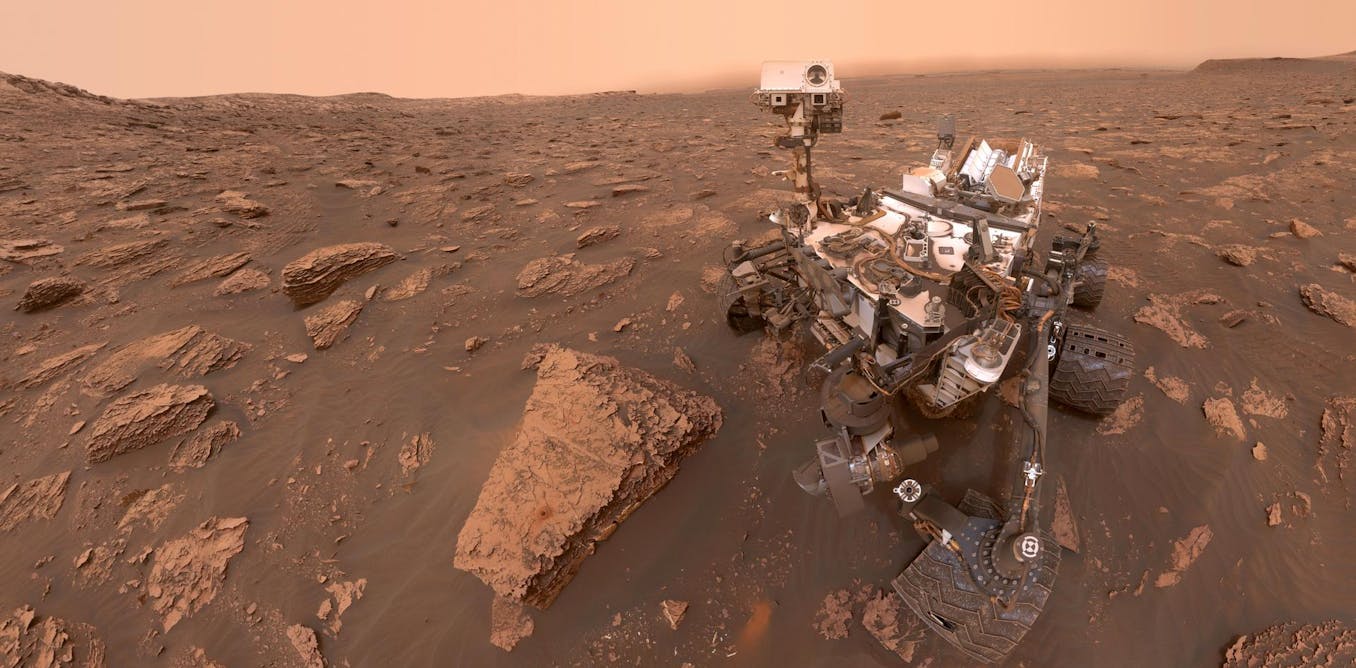

The Greeks proposed the idea that humans are a form of artificial intelligence. Prometheus and Hephaestus use technology to manufacture men and women. As historian Adrienne Mayor reveals in her book Gods and Robots, the ancients often depicted Prometheus as a craftsman, using ordinary tools to create human beings in an ordinary workshop.

If Prometheus gave us the fire of the gods, it would seem to follow that we can use this fire to make our own intelligent beings. Such stories abound in Ancient Greek literature, from the inventor Daedalus, who created statues that came to life, to the witch Medea, who could restore youth and potency with her cunning drugs. Greek inventors also constructed mechanical computers for astronomy and remarkable moving figures powered by gravity, water and air.

The Pope and the chatbot

2,700 years have passed since Hesiod first wrote down the story of Prometheus. In the ensuing centuries, the myth has been endlessly retold, especially since the publication of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein; or the Modern Prometheus in 1818.

But the myth is not always told as fiction. Here are two historical examples where the myth of Prometheus seemed to come true.

Gerbert of Aurillac was the Prometheus of the 10th century. He was born in the early 940s CE, went to school at Aurillac Abbey, and became a monk himself. He proceeded to master every known branch of learning. In the year 999, he was elected Pope. He died in 1003 under his pontifical name, Sylvester II.

Rumours about Gerbert spread wildly across Europe. Within a century of his death, his life had already become legend. One of the most famous legends, and the most pertinent in our age of AI hype, is that of Gerbert’s “brazen head”. The legend was told in the 1120s by the English historian William of Malmesbury, in his well researched and highly regarded book, Deeds of the English Kings.

Gerbert was deeply learned in astronomy, a science of prediction. Astronomers could use the astrolabe to predict the position of the stars and foresee cosmological events such as eclipses. According to William, Gerbert used his knowledge of astronomy to construct a talking head. After inspecting the movements of the stars and planets, he cast a head in bronze that could answer yes-or-no questions.

First Gerbert asked the head: “Will I become Pope?”

“Yes,” answered the head.

Then Gerbert asked: “Will I die before I sing mass in Jerusalem?”

“No,” the head replied.

In both cases, the head was correct, though not as Gerbert anticipated. He did become Pope, and he sensibly avoided going on pilgrimage to Jerusalem. One day, however, he sang mass at Santa Croce in Gerusalemme in Rome. Unfortunately for Gerbert, Santa Croce in Gerusalemme was known in those days simply as “Jerusalem”.

Gerbert sickened and died. On his deathbed, he asked his attendants to cut up his body and cast away the pieces, so he could go to his true master, Satan. In this way, he was, like Prometheus, punished for his theft of fire.

Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

It is a thrilling story. It is not clear whether William of Malmesbury actually believed it. But he does try to persuade his readers that it is plausible. Why did this great historian with a devotion to the truth insert some fanciful legends about a French pope into his history of England? Good question!

Is it so fanciful to believe that an advanced astronomer might build a general-purpose prediction machine? In those days, astronomy was the most powerful science of prediction. The sober and scholarly William was at least willing to entertain the idea that brilliant advances in astronomy might make it possible for a Pope to build an intelligent chatbot.

Today, that same possibility is credited to machine-learning algorithms, which can predict which ad you will click, which movie you will watch, which word you will type next. We can be forgiven for falling under the same spell.

The anatomist and the automaton

The Prometheus of the 18th century was Jacques de Vaucanson, at least according to Voltaire:

Bold Vaucanson, rival of Prometheus,

Seems, imitating the springs of nature,

To steal the fire of heaven to animate the body.

Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Vaucanson was a great machinist, famous for his automata. These were clockwork devices that realistically simulated human or animal anatomy. Philosophers of the time believed that the body was a machine – so why couldn’t a machinist build one?

Sometimes Vaucanson’s automata were scientifically significant. He constructed a piper, for example, that had lips and lungs and fingers, and blew the pipe in much the same way a human would. Historian Jessica Riskin explains in her book The Restless Clock that Vaucanson had to make significant discoveries in acoustics in order to make his piper play in tune.

Sometimes his automata were less scientific. His digesting duck was hugely famous, but turned out to be fraudulent. It appeared to eat and digest food, but its poos were in fact prefabricated pellets hidden inside the mechanism.

Vaucanson spent decades working on what he called a “moving anatomy”. In 1741, he presented a plan to the Lyons Academy to build an “imitation of all animal operations”. Twenty years later, he was at it again. He secured support from King Louis XV to build a simulation of the circulatory system. He claimed he could build a complete, living artificial body.

Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

There is no evidence that Vaucanson ever completed a whole body. In the end, he couldn’t live up to the hype. But many of his contemporaries believed he could do it. They wanted to believe in his magical mechanisms. They wished he would seize the fire of life.

If Vaucanson could manufacture a new human body, couldn’t he also repair an existing one? This is the promise of some AI companies today. According to Dario Amodei, CEO of Anthropic, AI will soon allow people “to live as long as they want”. Immortality seems like an attractive investment.

Sylvester II and Vaucanson were great technologists, but neither was a Prometheus. They stole no fire from the gods. Will the aspiring Prometheans of Silicon Valley succeed where their predecessors have failed? If only we had Sylvester II’s brazen head, we could ask it.

The post “‘Artificial intelligence’ myths have existed for centuries – from the ancient Greeks to a pope’s chatbot” by Michael Falk, Senior Lecturer in Digital Studies, The University of Melbourne was published on 12/10/2025 by theconversation.com