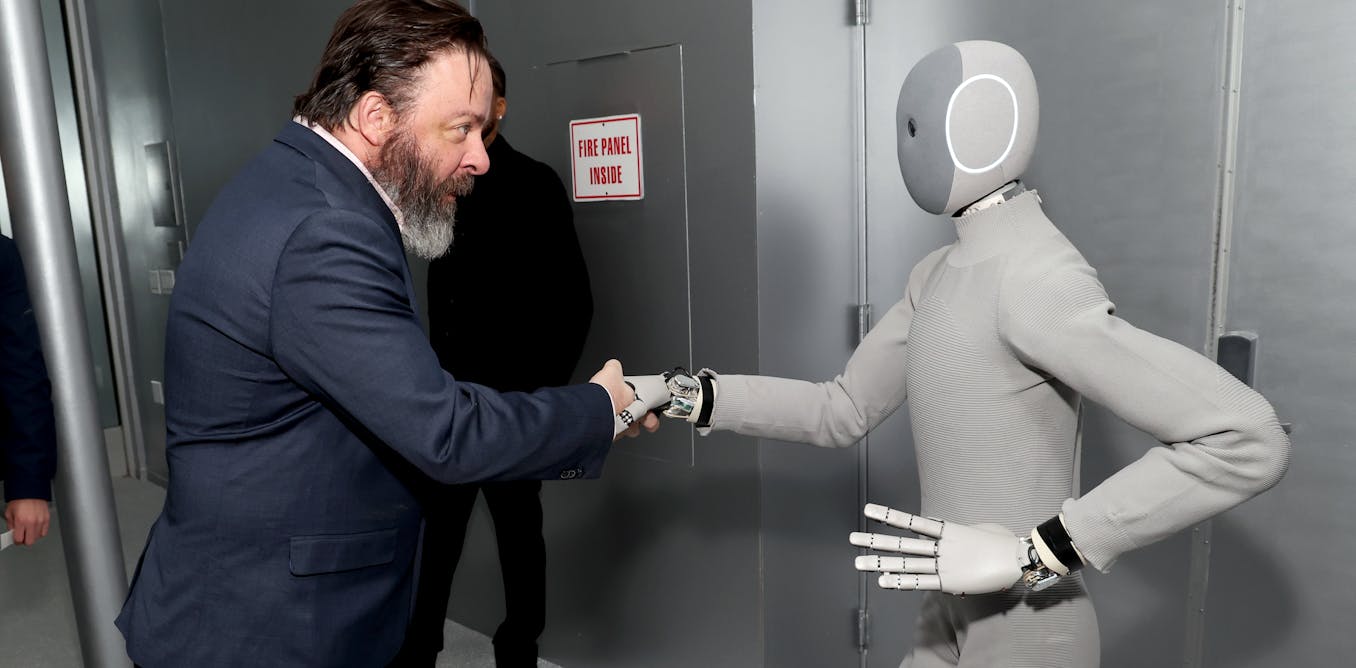

From ancient slavery to the factory floor, progress has often relied on the exploitation of human beings. We might like to believe those days are well behind us. But in the digital age, AI and the metaverse risk repeating that pattern with new forms of invisible labour and inequality.

Ridley Scott’s 2000 film Gladiator told the story of Maximus Decimus Meridius, a betrayed Roman general who becomes enslaved and must fight as a gladiator to entertain the Roman elite. The sequel offered a new perspective on cycles of exploitation and the struggle for dignity.

Both films hold a mirror to modern forms of servitude. These stories remain unsettlingly relevant even today, where the metaverse, AI and digital economies are reshaping labour dynamics.

As AI takes over key logistics and procurement processes, new blind spots can emerge. AI tools designed to monitor efficiency and productivity, for example, can also be misused to micromanage workers. A 2022 investigation found that eight of the ten largest US employers use AI to track worker productivity, particularly in low-wage digital jobs.

Then there are the low-wage workers who moderate online content, protecting metaverse users from harmful material. Research has found that moderators can experience anxiety, depression, nightmares, fatigue and panic attacks due to their exposure to disturbing content. This can include images and videos of child abuse and violence, as well as cruelty and humiliation.

Another study revealed how content moderators in places such as the Philippines, India, Mexico and Silicon Valley suffer psychological trauma, exploitative contracts and a lack of protections. Companies in this case effectively outsource the psychological toll of this work. While it’s true that a smaller number of moderators are employed in higher-income countries, most content moderation is outsourced to lower-wage regions.

And although AI can help to flag and filter harmful content, research shows that manual content moderation remains critical in immersive environments.

Nwz/Shutterstock

The metaverse is often hyped as a space for creativity, freedom and new economic opportunities. Large tech companies promise users the ability to build virtual worlds, participate in decentralised economies and redefine their work-life balance. But again, this vision obscures the potential exploitation embedded within these systems.

Consider the rise of “play-to-earn” gaming platforms, where users earn cryptocurrency or digital assets by playing games. While it appears empowering, it often relies on labour from marginalised regions where players hope to earn a living but end up facing financial losses.

These can arise from the initial outlays required to play. This makes them players in name only, as they participate out of economic necessity.

Another practice in virtual economies is “gold farming”. This originated in so-called “massively multiplayer online role-playing games”, and involves “worker-players” repeatedly performing monotonous in-game tasks, known as “grinding”. This generates virtual currency or items, which are then sold for real-world money to higher-income “leisure-players”.

Gold-farming operations are typically run in low-income countries, where worker-players dedicate long hours for meagre pay while wealthier players benefit from purchasing the virtual goods and services.

In the metaverse, this practice is evolving into large-scale digital labour, where workers farm virtual goods in gig-like conditions without protections, benefits or fair wages.

Yet, empirical research on these forms of digital labour remains limited, even as these systems expand at remarkable speed.

Entertainment and ethics

The metaverse cannot exist without a vast material supply chain. Take, for instance, the workers who endure harsh conditions to produce the hardware that powers it. The mining of earth metals, critical for electronics like VR headsets, frequently involves exploitative labour practices.

The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) accounts for more than 50% of global cobalt reserves and is the second largest producer of copper in the world. But first-hand reports reveal that miners work in shafts as deep as 100 metres with no safety protection. Workers, including children, risk their lives for minimal pay under dangerous conditions.

The demand for critical minerals is intensifying. The International Energy Agency has projected that demand for cobalt, lithium, nickel and copper could triple or more by 2050. To meet this demand, more than 350 new mines may be needed by 2035, increasing concerns about human rights.

The metaverse promises rich user experiences but also deepens the risk of exploitation. The escapism it provides often comes at the expense of unseen workers trapped in unequal systems. The growing number of people serving it certainly warrants more attention from regulators, unions and authorities.

However, the metaverse also poses new and unique challenges for regulation because it lacks physical boundaries. This is made harder by its fragmented, decentralised governance and the speed of its evolution.

But there are signs of progress. Governments are revisiting regulations to enforce ethical labour practices in supply chains. And the EU’s corporate sustainability due diligence directive, adopted in July 2024, represents a significant step in holding companies accountable for human rights violations.

Similarly, the UK’s modern slavery statement requires businesses to do more to identify and mitigate forced labour risks in their supply chains. However, as the metaverse evolves, regulatory frameworks will need to adapt rapidly.

Exploitation in labour systems is not new, but the forms it takes in digital environments can be harder to detect and easier to scale. That is why staying attuned to these emerging dynamics matters.

The metaverse has the potential to democratise access to information, connection and opportunity. But its foundations must be free from the taint of exploitation.

We are all spectators, witnessing mostly the convenience of the end-user experience. But how different are we from the crowds who cheered for the gladiators in the Colosseum? In ancient Rome, suffering was visible yet overlooked; in the digital world it is perhaps easier to look away. The answer lies in regulation, accountability and a collective commitment to ensuring that the digital age does not repeat historical cruelties.

The post “The metaverse is ushering in a new era of behind-the-scenes exploitation” by Vincent Charles, Reader in AI for Business and Management Science, Queen’s University Belfast was published on 12/09/2025 by theconversation.com