For the UK after Brexit, it is tempting to imagine that regulation no longer comes from Brussels. Yet one of the most significant pieces of digital legislation anywhere in the world – the EU’s Artificial Intelligence Act – is now coming into force, and its effects will reach UK companies, regulators and citizens.

AI is already threaded through daily life: in how loans are priced, how job applications are sifted, how fraud is detected, how medical services are triaged, and how online content is pushed.

The EU’s AI Act, which is entering into force in stages, is an attempt to make those invisible processes safer, more accountable and closer to European values. It reflects a deliberate choice to govern the social and economic consequences of automated decision-making.

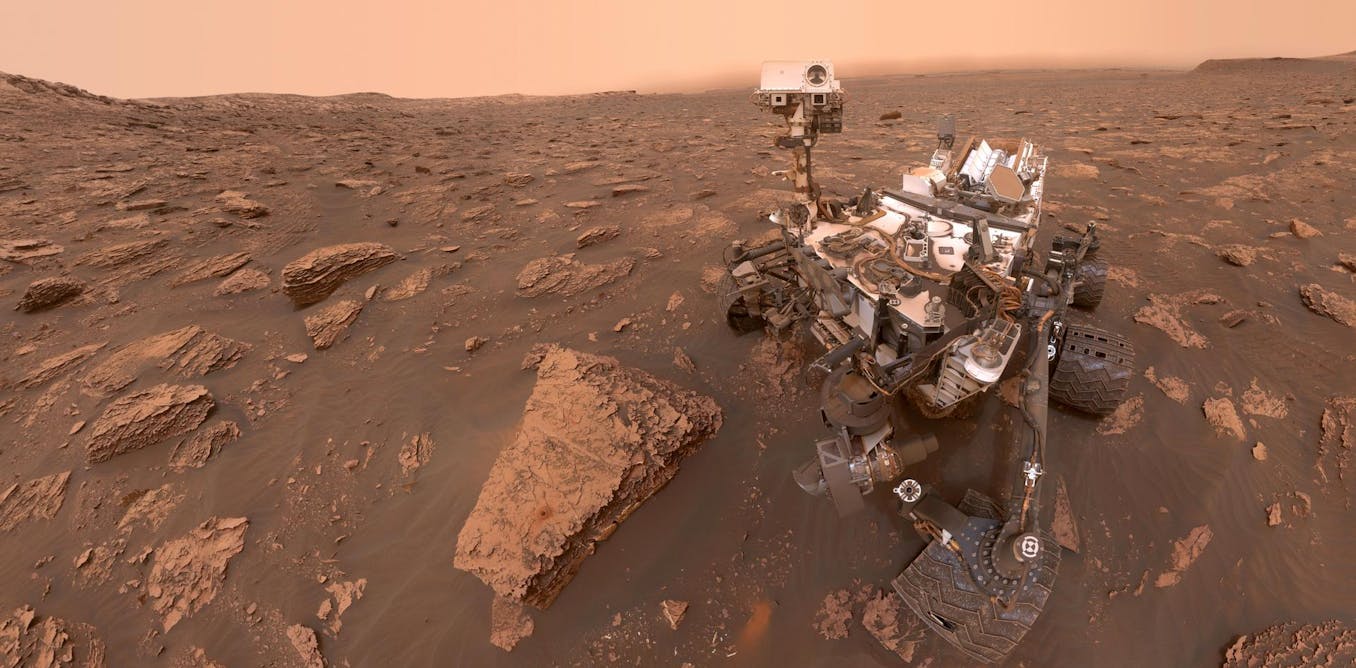

The act aims to harness the innovative power of AI while protecting EU citizens from its harms. The UK has chosen a lighter regulatory path, but it will not be immune from the act’s consequences. Through the AI Office and national enforcement authorities, the EU will be able to sanction UK companies that have operations in the bloc, regardless of where they have their headquarters.

The act enables authorities to impose fines or demand that systems be changed. This is a signal that the EU is now treating AI governance as a compliance issue rather than a matter of voluntary ethics. My research outlines the power of the enforcement provisions, particularly their influence on how AI systems will be designed, deployed or even withdrawn from the market.

Many of the systems most relevant to everyday life, such as those used in employment, healthcare or credit scoring, are now deemed “high-risk” under the act. AI applications in these scenarios must satisfy demanding standards around data, transparency, documentation, human oversight and incident reporting. Some practices, such as systems that use biometric data to exploit or distort people’s behaviour by targeting vulnerabilities such as age, disability or emotional state, are simply banned.

The regime also extends to general-purpose AI – the models that underpin everything from chatbots to content generators. These are not automatically classified as high-risk but are subject to transparency and governance obligations alongside stricter safeguards in situations where the AI could have large-scale or systemic effects.

This approach effectively exports Europe’s expectations to the world. The so-called “Brussels effect” operates on a simple logic. Large companies prefer to comply with a single global standard rather than maintain separate regional versions of their systems. Firms that want access to Europe’s 450 million consumers will therefore simply adapt. Over time, that becomes the global norm.

Read more:

UK government’s AI plan gives a glimpse of how it plans to regulate the technology

The UK has opted for a far less prescriptive model. While its own comprehensive AI legislation appears to be in doubt, regulators – including the Information Commissioner’s Office, Financial Conduct Authority and Competition and Markets Authority – examine broad principles of safety, transparency and accountability within their own remits.

This has the virtue of agility: regulators can adjust their guidance as required without waiting for legislation. But this also shifts a greater burden on to firms, which must anticipate regulatory expectations across multiple authorities. This is a deliberate choice to rely on regulatory experimentation and sector-specific expertise rather than a single, centralised rulebook.

Agility has trade-offs. For small and medium-sized firms trying to understand their obligations, the EU’s clarity might seem more manageable.

There is also a risk of regulatory misalignment. If Europe’s model becomes the global reference point, UK firms may find themselves working to both the domestic standard and the European one demanded by their clients. Maintaining this will be costly and is rarely sustainable.

Why UK companies will be affected

Perhaps the most consequential – but least widely understood – aspect of the EU’s AI Act is that extraterritorial scope that I mentioned earlier. The act applies not only to companies based inside the EU but also to any provider whose systems are either placed on the EU market or whose outputs are used within the bloc.

This captures a vast range of UK activity. A London fintech offering AI-driven fraud detection to a Dutch bank, a UK insurer using AI tools that inform decisions about policyholders in Spain, or a British manufacturer exporting devices to France – all of these fall squarely within European regulation.

My research also covers the obligations for banks and insurers – they may need robust documentation, human-oversight procedures, incident-reporting mechanisms and quality-management systems as a matter of course.

Even developers of general-purpose AI models could find themselves under fire, particularly where regulators identify systemic risks or gaps in transparency that warrant closer scrutiny or corrective action.

For many UK firms, the more pragmatic choice will be to design their systems to EU standards from the outset rather than produce separate versions for different markets.

Andrey_Popov/Shutterstock

Although this debate often sounds abstract, its effects are anything but. Tools that determine your access to credit, employment, healthcare or essential public services increasingly rely on AI. The standards imposed by the EU – particularly requirements to minimise discrimination, ensure transparency and maintain human oversight – are likely to spill over into UK practice simply because large providers will adapt globally to meet European expectations.

Europe has made its choice: a sweeping, legally binding regime designed to shape AI according to principles of safety, fairness and accountability. The UK has chosen a more permissive, innovation-first path. Geography, economics and shared digital infrastructure all ensure that Europe’s regulatory pull will reach the UK, whether through markets, supply chains or public expectations.

The AI Act is a blueprint for the kind of digital society Europe wants – and, by extension, a framework that UK firms will increasingly need to navigate. In an age when algorithms determine opportunity, risk and access, the rules that govern them matter to all of us.

The post “The EU’s new AI rulebook will affect businesses and consumers in the UK too” by Maria Lucia Passador, Assistant Professor, Department of Law, Bocconi University was published on 01/20/2026 by theconversation.com