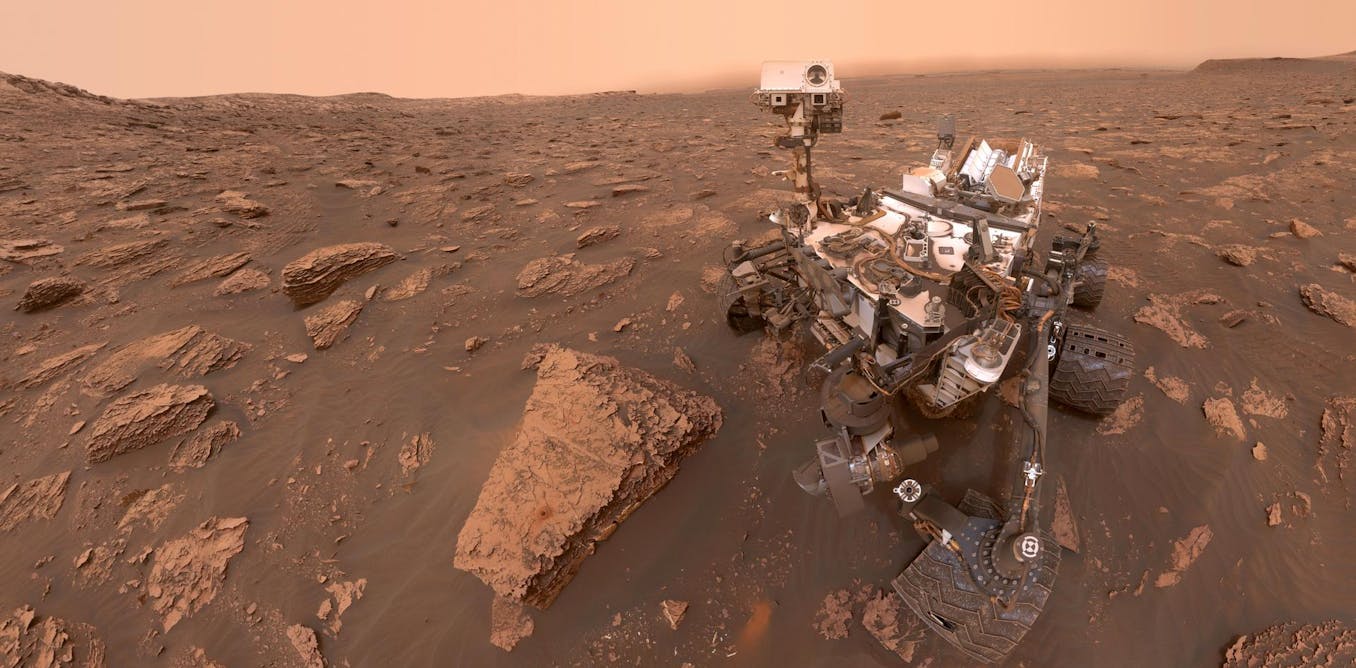

Last September, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) unleashed teams of robots on simulated mass-casualty scenarios, including an airplane crash and a night ambush. The robots’ job was to find victims and estimate the severity of their injuries, with the goal of helping human medics get to the people who need them the most.

Kimberly Elenberg

Kimberly Elenberg is a principal project scientist with the Auton Lab of Carnegie Mellon University’s Robotics Institute. Before joining CMU, Elenberg spent 28 years as an army and U.S. Public Health Service nurse, which included 19 deployments and serving as the principal strategist for incident response at the Pentagon.

The final event of the DARPA Triage Challenge will take place in November, and Team Chiron from Carnegie Mellon University will be competing, using a squad of quadruped robots and drones. The team is led by Kimberly Elenberg, whose 28-year career as an army and U.S. Public Health Service nurse took her from combat surgical teams to incident response strategy at the Pentagon.

Why do we need robots for triage?

Kimberly Elenberg: We simply do not have enough responders for mass-casualty incidents. The drones and ground robots that we’re developing can give us the perspective that we need to identify where people are, assess who’s most at risk, and figure out how responders can get to them most efficiently.

When could you have used robots like these?

Elenberg: On the way to one of the challenge events, there was a four-car accident on a back road. For me on my own, that was a mass casualty event. I could hear some people yelling and see others walking around, and so I was able to reason that those people could breathe and move.

In the fourth car, I had to crawl inside to reach a gentleman who was slumped over with an occluded airway. I was able to lift his head until I could hear him breathing. I could see that he was hemorrhaging and feel that he was going into shock because his skin was cold. A robot couldn’t have gotten inside of the car to make those assessments.

This challenge involves enabling robots to remotely collect this data—can they detect heart rate from changes in skin color or hear breathing from a distance? If I’d had these capabilities, it would have helped me identify the person at greatest risk and gotten to them first.

How do you design tech for triage?

Elenberg: The system has to be simple. For example, I can’t have a device that’s going to force a medic to take their hands away from their patient. What we came up with is a vest-mounted Android phone that flips down at chest height to display a map that has the GPS location of all of the casualties on it and their triage priority as colored dots, autonomously populated from the team of robots.

Are the robots living up to the hype?

Elenberg: From my time in service, I know the only way to understand true capability is to build it, test it, and break it. With this challenge, I’m learning through end-to-end systems integration—sensing, communications, autonomy, and field testing in real environments. This is art and science coming together, and while the technology still has limitations, the pace of progress is extraordinary.

What would be a win for you?

Elenberg: I already feel like we’ve won. Showing responders exactly where casualties are and estimating who needs attention most—that’s a huge step forward for disaster medicine. The next milestone is recognizing specific injury patterns and the likely life-saving interventions needed, but that will come.

This article appears in the January 2026 print issue as “Kimberly Elenberg.”

The post “Teams of Robots Compete to Save Lives on the Battlefield” by Evan Ackerman was published on 12/31/2025 by spectrum.ieee.org