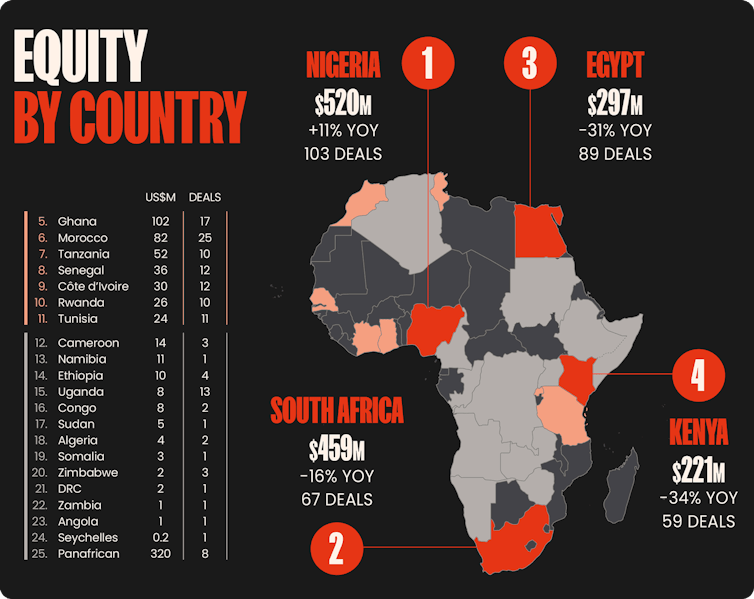

One year after the AI Summit in Paris, the international community will meet again this week in New Delhi for the Global Summit on Artificial Intelligence, whose objective will notably be to support the diffusion of AI uses in developing countries. In Africa, AI and Tech investment remains concentrated in the “Big Four” – South Africa, Egypt, Kenya and Nigeria – at the expense of other countries across the continent. This analysis explores the causes of this imbalance and the levers that could be used to better direct capital.

Between 2015 and 2022, investment in African start-ups experienced unprecedented growth: the number of start-ups receiving funding increased more than sevenfold, driven by the expansion of mobile technologies, fintech and a massive inflow of international capital. However, from 2022 onwards, tighter economic conditions led to a “funding squeeze” (a reduction in venture capital investment) that was more severe for African start-ups than in other regions of the world. This trend further reinforced the concentration of capital in the countries with the most developed start-up ecosystems, namely South Africa, Egypt, Kenya and Nigeria.

There is, however, a strong case for ensuring that these investments are more evenly distributed across the continent. Beyond stimulating economic activity, the technological innovations developed by these start-ups represent a significant lever for development, as they offer solutions tailored to local contexts: targeted financial solutions, improved agricultural productivity, strengthened health and education systems, and responses to priority climate challenges, etc.

Partech, 2024 Africa Tech Venture Capital

Concentration of investment in the Big Four

In the early 2020s, the expression “Big Four” emerged to describe Africa’s main tech markets: South Africa, Egypt, Kenya and Nigeria. The notion, likely inspired by the term Big Tech, suggests the existence of “champion countries” in the technology sector.

In 2024, the Big Four captured 67% of equity tech funding (investments made in exchange for shares in technology companies). In detail, the shares captured by each country were distributed as follows: around 24% for Kenya, 20% for South Africa, and 13.5% each for Egypt and Nigeria.

This funding cluster is not only geographical; it also has a strong sectoral dimension. Capital is largely directed toward sectors perceived as less risky, such as digital finance or “fintech”, often at the expense of areas such as edtech and cleantech – that is, technologies dedicated to education and to environmental solutions, respectively.

An estimated 60%-70% of funds raised in Africa come from international investors, particularly for funding rounds over 10-20 million dollars. These investments, often concentrated in more structured markets, represent the most visible transactions, but also those considered the least risky.

Emerging peripheral ecosystems and potential that remains insufficiently converted into investment

While the Big Four concentrate the majority of investment, several African countries now demonstrate proven potential in AI and a pool of promising start-ups, without capturing investment volumes commensurate with that potential.

Countries such as Ghana, Morocco, Senegal, Tunisia and Rwanda form an emerging group whose members have favourable AI fundamentals but remain underfunded. This gap is all the more striking given that Ghana, Morocco and Tunisia, all of which have dynamic start-up pools, together account for around 17% of African technology companies outside the Big Four. At the same time, local financial structures struggle to meet these funding needs in geographies perceived as peripheral.

This difficulty in attracting investment can be explained in particular by institutional and business ecosystems that still need strengthening, as the performance of technology companies relies on the existence of structured entrepreneurial ecosystems that enable access to knowledge, skilled labour, and support mechanisms (accelerators, incubators and investors).

Finally, it is important to recall that these weaknesses are part of a broader context: in 2020, the entire African continent accounted for only 0.4% of global venture capital flows and currently represents just 2.5% of the global AI market. Emerging countries outside the Big Four are therefore mechanically disadvantaged in a competition that is already highly concentrated.

Partech, 2024 Africa Tech Venture Capital

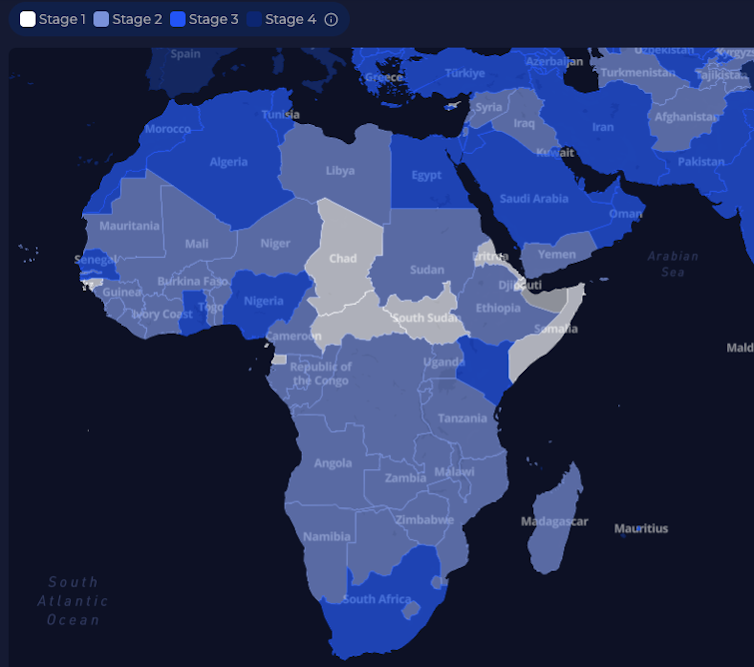

Steering investment to prepare countries for AI

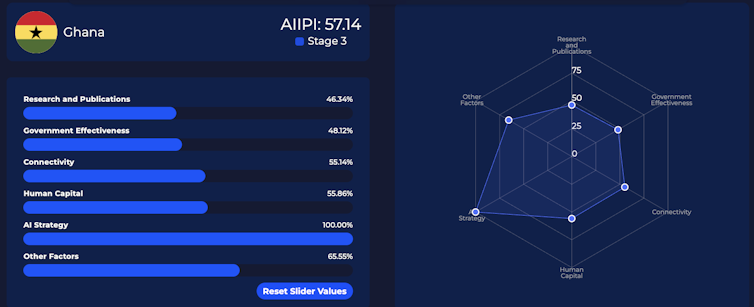

To attract capital toward AI start-ups, a country must itself be ready for AI. The adoption of AI at the national level does not depend solely on technological factors. The AI Investment Potential Index (AIIPI), a research initiative, highlights that this adoption also relies on economic, political and social factors. As a result, increasing a country’s AI potential requires not only strengthening energy and connectivity infrastructure, but also improving governance standards, public sector effectiveness and human capital.

Priority actions vary depending on countries’ level of advancement in AI. In more advanced countries, such as South Africa or Morocco, the challenge is more about supporting research, optimising AI applications and attracting strategic investment. In countries with more moderate scores, priorities tend to focus on strengthening connectivity infrastructure, human capital and regulatory frameworks.

The platform aipotentialindex.org enables, among other things, to visualise the index’s results at a global level and to identify the areas in which countries can invest to increase their AI investment potential (research, government effectiveness, connectivity, human capital, AI strategies, etc.). The AIIPI helps investors not only identify countries that are already advanced in AI, but also those with untapped potential. For public decision-makers and development actors, it provides a framework for prioritising reforms and investment.

aipotentialindex.org

aipotentialindex.org

Sovereign funds and instruments dedicated to new technologies

Once a country’s AI investment strategy has been defined, the question of AI financing instruments arises. At the continental level, several instruments dedicated to technology and AI are emerging. Development finance institutions, such as the African Development Bank or the West African Development Bank, are launching initiatives aimed at supporting the growth of the continent’s digital economy.

At national level, African Sovereign Wealth Funds (SWFs) provide an additional channel to support AI and start-up financing across the continent. These funds, such as the Mohammed VI Fund in Morocco or the Pula Fund in Botswana, mobilise public savings for long-term economic development and work in partnership with development banks.

Partnerships as powerful levers for start-up financing

Financing digital and AI infrastructure alone is not enough to build start-up ecosystems capable of driving economic growth. International public-private partnerships also play a significant role. The Choose Africa 2 initiative, led by AFD and Bpifrance, aims to address financing constraints facing entrepreneurship across the continent, particularly at the earliest stages. Support mechanisms, like Digital Africa, bringing together public actors and local partners enable small-ticket investments in early-stage “Tech for Good” start-ups, whose technologies generate strategic, social and environmental impact.

While these mechanisms are not enough on their own to correct investment imbalances, they can nevertheless help broaden access to financing beyond the ecosystems that are traditionally best resourced.

Central political, strategic and legal leadership

Financial investment alone is not sufficient and must be supported by strong political ambition. Legislative and strategic frameworks put in place at national and continental levels are key structural levers for the growth of digital start-ups in Africa.

On the one hand, strategies led by the African Union, including the Digital Transformation Strategy for Africa, the Continental Artificial Intelligence Strategy and the African Digital Compact, provide roadmaps enabling states to accelerate digital transformation. There are also national-level instruments, such as Tunisia’s “Start-up Act” law or national AI strategies, such as the one published by Ghana, which sets out the country’s ambition to become Africa’s “AI Hub.”

Finally, a major political commitment was made at last April’s Global AI Summit in Kigali, where 52 African countries announced the creation of a 60-billion-dollar African AI Fund combining public, private and philanthropic capital. This initiative illustrates a strategic ambition across the continent: positioning Africa around these emerging technological challenges. However, these AI-focused funds may face governance and financial structuring challenges. There remains a risk that they could reproduce asymmetries already observed in sovereign wealth funds if transparency mechanisms are not put in place. Their impact will, therefore, depend on the establishment of standards and governance tools adapted to emerging technological challenges.

These frameworks create the initial conditions needed for the emergence of local AI solutions and provide a structuring strategic framework. Their impact on investor confidence will, however, depend on how effectively they are aligned with appropriate financing mechanisms and strengthened local capacities.

This article was co-written with Anastesia Taieb, Innovation Officer at AFD, and Emma Pericard, Digital Africa’s representative to the EU.

A weekly e-mail in English featuring expertise from scholars and researchers. It provides an introduction to the diversity of research coming out of the continent and considers some of the key issues facing European countries. Get the newsletter!

The post “why AI start-up funding in Africa needs rethinking” by Claire Zanuso, PhD, économiste du développement, chargée de recherche et d’évaluation / Development economist, research and evaluation officer, Agence Française de Développement (AFD) was published on 02/17/2026 by theconversation.com

.jpg)