On March 8, the Conservative campaign team released a video of Pierre Poilievre on social media that drew unusual questions from some viewers. To many, Poilievre’s French sounded a little too smooth, and his complexion looked a little too perfect. The video had what’s known as an “uncanny valley” effect, causing some to wonder if the Poilievre they were seeing was even real.

Before long, the comments section filled with speculation: was this video AI-generated? Even a Liberal Party video mocking Poilievre’s comments led followers to ask why the Conservatives’ video sounded “so dubbed” and whether it was made with AI.

The ability to discern real from fake is seriously in jeopardy.

Poilievre’s smooth video offers an early answer to an open question: How might generative AI affect our election cycle? Our research team at Concordia University created a simulation to experiment with this question.

From a deepfake Mark Carney to AI-assisted fact-checkers, our preliminary results suggest that generative AI is not quite going to break elections, but it is likely to make them weirder.

A war game, but for elections?

Our simulation continued our past work in developing games to explore the Canadian media system.

Red teaming is a type of exercise that allows organizations to simulate attacks on their critical digital infrastructures and processes. It involves two teams — the attacking red team and the defending blue team. These exercises can help uncover vulnerability points within systems or defences and practice ways of correcting them.

Red-teaming has become a major part of cybersecurity and AI development. Here, developers and organizations stress-test their software and digital systems to understand how hackers or other “bad actors” might try to manipulate or crash them.

Fraudulent Futures

Our simulation, called Fraudulent Futures, attempted to evaluate AI’s impact on Canada’s political information cycle.

Four days into the ongoing federal election campaign, we ran the first test. A group of ex-journalists, cybersecurity experts and graduate students were pitted against each other to see who could leverage free AI tools best to push their agenda in a simulated social media environment based on our past research.

Hosted on a private Mastodon server securely shielded from public eyes, our two-hour long simulation quickly descended into silence as players played out their different roles on our simulated servers. Some played far-right influencers, others monarchists to make noise or journalists to cover events online. Players and organizers alike learned about generative AI’s capacity to create disinformation, and the difficulties faced by stakeholders trying to combat it.

Players connected to the server through their laptops and familiarized themselves with the dozens of free AI tools at their disposal. Shortly after, we shared an incriminating voice clone of Carney, created with an easily accessible online AI tool.

The Red Team was instructed to amplify the disinformation, while the Blue Team was directed to verify its authenticity and, if they determined it to be fake, mitigate the harm.

The Blue Team began testing the audio through AI detection tools and tried to publicize it was a fake. But for the Red Team, this hardly mattered. Fact-checking posts were quickly drowned out by a constant slew of new memes and fake images of angry Canadian voters denouncing Carney.

Whether the Carney clip was a deepfake or not didn’t really matter. The fact that we couldn’t tell for sure was enough to fuel endless online attacks.

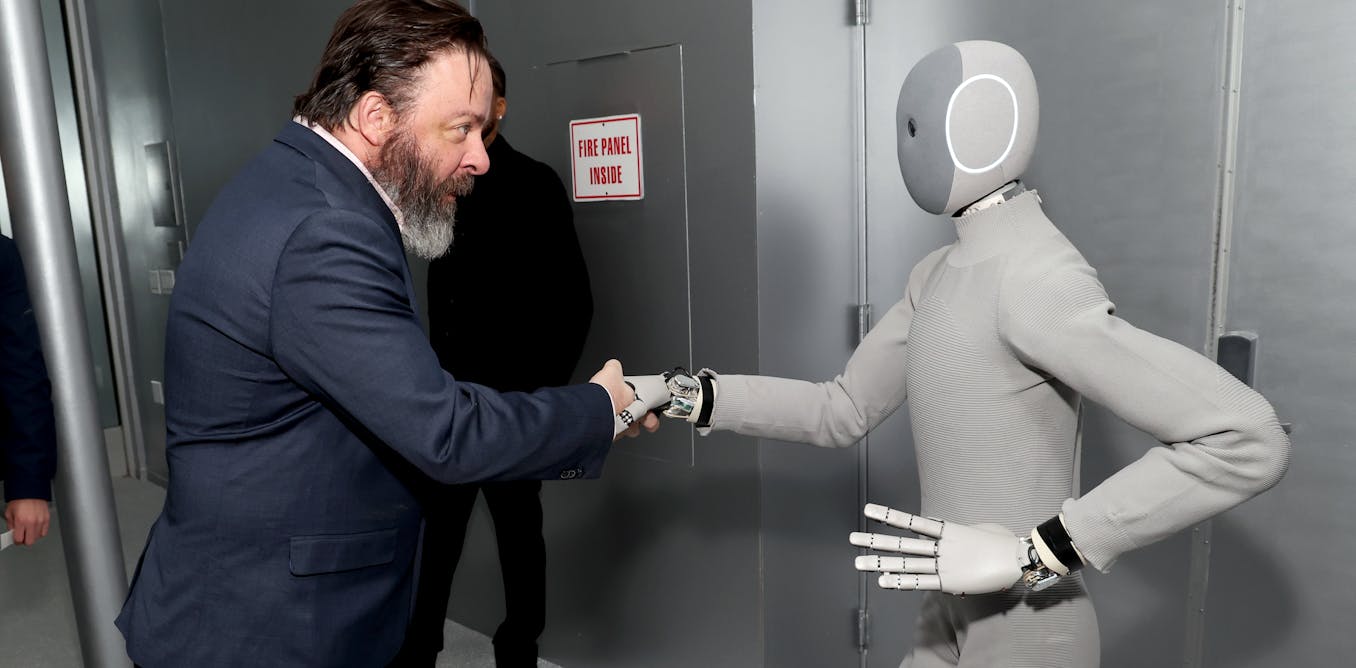

(Shutterstock)

Learning from an exercise

Our simulation purposefully exaggerated the information cycle. Yet the experience of trying to disrupt regular electoral processes was highly informative as a research method. Our research team found three major takeaways from the exercise:

1. Generative AI is easy to use for disruption

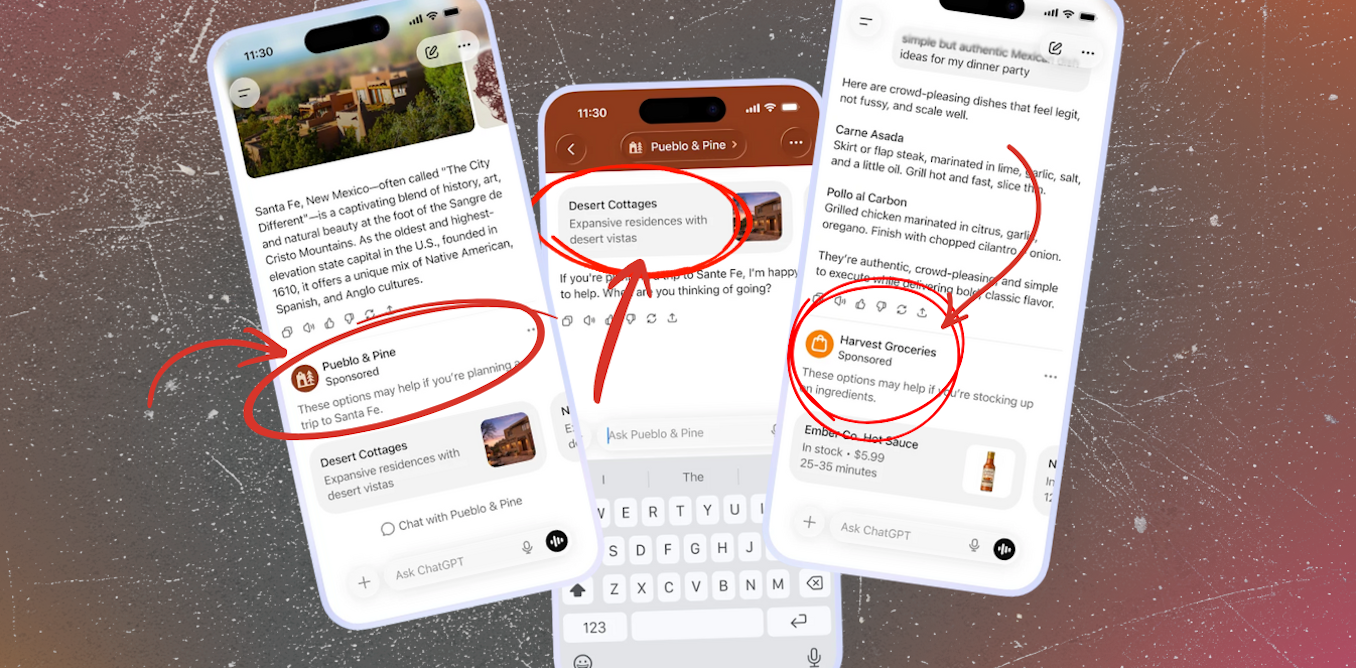

Many online AI tools claim to safeguard against generating content on elections and public figures. Despite those safeguards, players noted these tools would still generate political content.

The overall quality of the content produced was easy to distinguish as AI-generated. Yet, one of our players noted how simple it was “to generate and spam as much content as possible in order to muddy the waters on the digital landscape.”

2. AI detection tools won’t save us

AI detection tools can only go so far. They are rarely conclusive, and they may even take precedence over common sense. Players noted that even when they knew content was fake, they still felt they “needed to find the tool that would give the answer [they] want” to lend credibility to their interventions.

Most telling was how journalists on the Blue Team turned toward faulty detection tools over their own investigative work, a sign that users may be letting AI detection usurp journalistic skill.

With higher-quality content available in real-world situations, there might be a role for specialized AI detection tools in journalistic and election security processes — despite complex challenges — but these tools should not replace other investigative methods.

However, detection tools will likely only contribute to spreading uncertainty because of the lack of standards and confidence in their assessments.

3. Quality deepfakes are difficult to make

High-quality AI-generated content is achievable and has already caused many online and real-world harms and panics. However, our simulation helped confirm that quality deepfakes are difficult and time-consuming to make.

It is unlikely that the mass availability of generative AI will cause an overwhelming influx of high-quality deceptive content. These types of deepfakes will likely come from more organized, funded and specialized groups engaged in election interference.

Democracy in the age of AI

A major takeaway from our simulation was that the proliferation of AI slop and the stoking of uncertainty and distrust are easy to accomplish at a spam-like scale with freely accessible online tools and little to no prior knowledge or preparation.

Our red-teaming experiment was a first attempt to see how participants might use generative AI in elections. We’ll be working to improve and re-run the simulation to include the broader information cycle, with a particular eye towards better simulating Blue Team co-operation in the hopes of reflecting real-world efforts by journalists, election officials, political parties and others to uphold election integrity.

We anticipate that the Poilievre debate is just the beginning of a long string of incidents to come, where AI distorts our ability to discern the real from the fake. While everyone can play a role in combatting disinformation, hands-on experience and game-based media literacy have proven to be valuable tools. Our simulation proposes a new and engaging way to explore the impacts of AI on our media ecosystem.

The post “Lessons from a simulated war-game exercise” by Robert Marinov, PhD Candidate in Communication, Concordia University was published on 04/08/2025 by theconversation.com