The problem is simple: it’s hard to know whether a photo’s real or not anymore. Photo manipulation tools are so good, so common and easy to use, that a picture’s truthfulness is no longer guaranteed.

The situation got trickier with the uptake of generative artificial intelligence. Anyone with an internet connection can cook up just about any image, plausible or fantasy, with photorealistic quality, and present it as real. This affects our ability to discern truth in a world increasingly influenced by images.

Read more:

Can you tell the difference between real and fake news photos? Take the quiz to find out

I teach and research the ethics of artificial intelligence (AI), including how we use and understand digital images.

Many people ask how we can tell if an image has been changed, but that’s fast becoming too difficult. Instead, here I suggest a system where creators and users of images openly state what changes they’ve made. Any similar system will do, but new rules are needed if AI images are to be deployed ethically – at least among those who want to be trusted, especially media.

Doing nothing isn’t an option, because what we believe about media affects how much we trust each other and our institutions. There are several ways forward. Clear labelling of photos is one of them.

Deepfakes and fake news

Photo manipulation was once the preserve of government propaganda teams, and later, expert users of Photoshop, the popular software for editing, altering or creating digital images.

Today, digital photos are automatically subjected to colour-correcting filters on phones and cameras. Some social media tools automatically “prettify” users’ pictures of faces. Is a photo taken of oneself by oneself even real anymore?

Read more:

The use of deepfakes can sow doubt, creating confusion and distrust in viewers

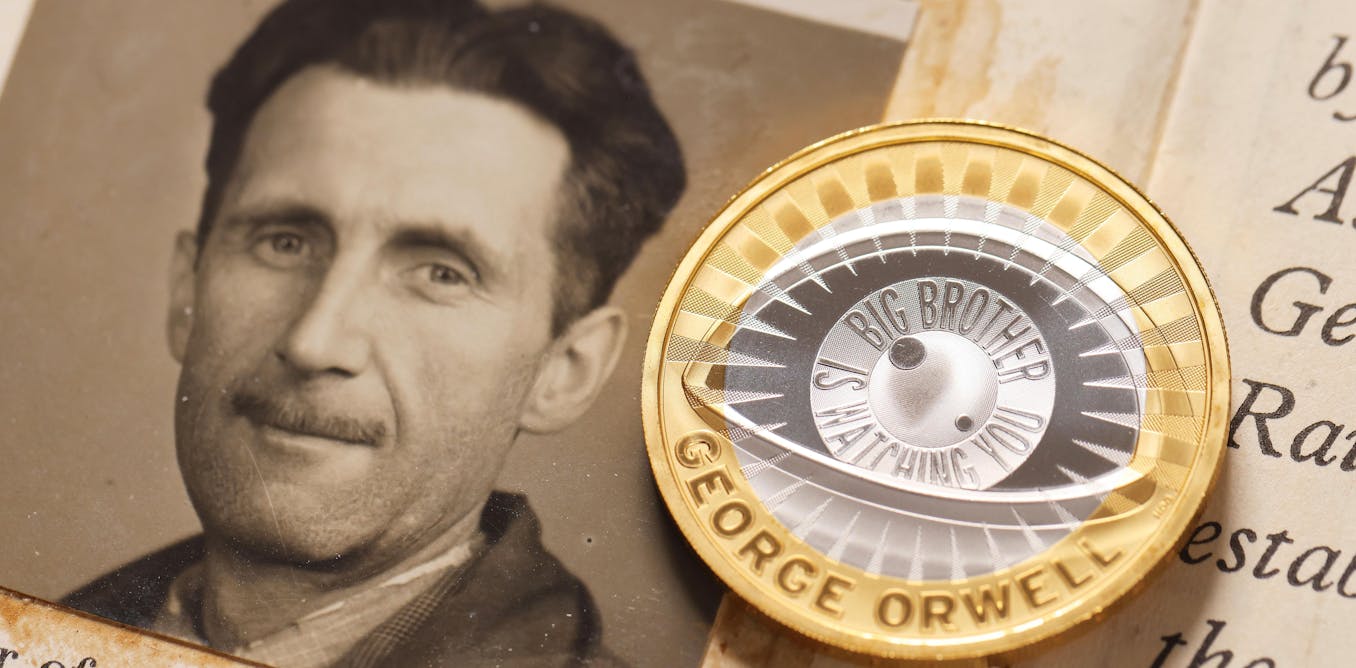

The basis of shared social understanding and consensus – trust regarding what one sees – is being eroded. This is accompanied by the apparent rise of untrustworthy (and often malicious) news reporting. We have new language for the situation: fake news (false reporting in general) and deepfakes (deliberately manipulated images, whether for waging war or garnering more social media followers).

Misinformation campaigns using manipulated images can sway elections, deepen divisions, even incite violence. Scepticism towards trustworthy media has untethered ordinary people from fact-based accounting of events, and has fuelled conspiracy theories and fringe groups.

Ethical questions

A further problem for producers of images (personal or professional) is the difficulty of knowing what’s permissable. In a world of doctored images, is it acceptable to prettify yourself? How about editing an ex-partner out of a picture and posting it online?

Would it matter if a well-respected western newspaper published a photo of Russian president Vladimir Putin pulling his face in disgust (an expression that he surely has made at some point, but of which no actual image has been captured, say) using AI?

The ethical boundaries blur further in highly charged contexts. Does it matter if opposition political ads against then-presidential candidate Barack Obama in the US deliberately darkened his skin?

Would generated images of dead bodies in Gaza be more palatable, perhaps more moral, than actual photographs of dead humans? Is a magazine cover showing a model digitally altered to unattainable beauty standards, while not declaring the level of photo manipulation, unethical?

A fix

Part of the solution to this social problem demands two simple and clear actions. First, declare that photo manipulation has taken place. Second, disclose what kind of photo manipulation was carried out.

The first step is straightforward: in the same way pictures are published with author credits, a clear and unobtrusive “enhancement acknowledgement” or EA should be added to caption lines.

Read more:

AI isn’t what we should be worried about – it’s the humans controlling it

The second is about how an image has been altered. Here I call for five “categories of manipulation” (not unlike a film rating). Accountability and clarity create an ethical foundation.

The five categories could be:

C – Corrected

Edits that preserve the essence of the original photo while refining its overall clarity or aesthetic appeal – like colour balance (such as contrast) or lens distortion. Such corrections are often automated (for instance by smartphone cameras) but can be performed manually.

E – Enhanced

Alterations that are mainly about colour or tone adjustments. This extends to slight cosmetic retouching, like the removal of minor blemishes (such as acne) or the artificial addition of makeup, provided the edits don’t reshape physical features or objects. This includes all filters involving colour changes.

B – Body manipulated

This is flagged when a physical feature is altered. Changes in body shape, like slimming arms or enlarging shoulders, or the altering of skin or hair colour, fall under this category.

O – Object manipulated

This declares that the physical position of an object has been changed. A finger or limb moved, a vase added, a person edited out, a background element added or removed.

G – Generated

Entirely fabricated yet photorealistic depictions, such as a scene that never existed, must be flagged here. So, all images created digitally, including by generative AI, but limited to photographic depictions. (An AI-generated cartoon of the pope would be excluded, but a photo-like picture of the pontiff in a puffer jacket is rated G.)

Martin Bekker

The suggested categories are value-blind: they are (or ought to be) triggered simply by the occurrence of any manipulation. So, colour filters applied to an image of a politician trigger an E category, whether the alteration makes the person appear friendlier or scarier. A critical feature for accepting a rating system like this is that it is transparent and unbiased.

The CEBOG categories above aren’t fixed, there may be overlap: B (Body manipulated) might often imply E (Enhanced), for example.

Feasibility

Responsible photo manipulation software may automatically indicate to users the class of photo manipulation carried out. If needed it could watermark it, or it could simply capture it in the picture’s metadata (as with data about the source, owner or photographer). Automation could very well ensure ease of use, and perhaps reduce human error, encouraging consistent application across platforms.

Read more:

Can you spot a financial fake? How AI is raising our risks of billing fraud

Of course, displaying the rating will ultimately be an editorial decision, and good users, like good editors, will do this responsibly, hopefully maintaining or improving the reputation of their images and publications. While one would hope that social media would buy into this kind of editorial ideal and encourage labelled images, much room for ambiguity and deception remains.

The success of an initiative like this hinges on technology developers, media organisations and policymakers collaborating to create a shared commitment to transparency in digital media.

The post “How to tell if a photo’s fake? You probably can’t. That’s why new rules are needed” by Martin Bekker, Computational Social Scientist, University of the Witwatersrand was published on 05/08/2025 by theconversation.com