Supermarket shelves can look full despite the food systems underneath them being under strain. Fruit may be stacked neatly, chilled meat may be in place. It appears that supply chains are functioning well. But appearances can be deceiving.

Today, food moves through supply chains because it is recognised by databases, platforms and automated approval systems. If a digital system cannot confirm a shipment, the food cannot be released, insured, sold, or legally distributed. In practical terms, food that cannot be “seen” digitally becomes unusable.

This affects the resilience of the UK food system , and is increasingly identified as a critical vulnerability.

Look at the consequences, for example, when recent cyberattacks on grocery and food distribution networks disrupted operations at multiple major US grocery chains. This took online ordering and other digital systems down and delayed deliveries even though physical stocks were available.

Part of the problem here is that key decisions are made by automated or opaque systems that cannot be easily explained or challenged. Manual backups are also being removed in the name of efficiency.

This digital shift is happening around the world, in supermarkets and in farming, and has delivered efficiency gains, but it has also intensified structural pressures across logistics and transport, particularly in supply chains which are set up to deliver at the last minute.

Using AI

AI and data-driven systems now shape decisions across agriculture and food delivery. They are used to forecast demand, optimise planting, prioritise shipments, and manage inventories. Official reviews of the use of AI across production, processing, and distribution show that these tools are now embedded across most stages of the UK food system. But there are risks.

When decisions about food allocation cannot be explained or reviewed, authority shifts away from human judgment and into software rules. Put simply, businesses are choosing automation over humans to save time and cut costs. As a result, decisions about food movement and access are increasingly made by systems that people cannot easily question or override.

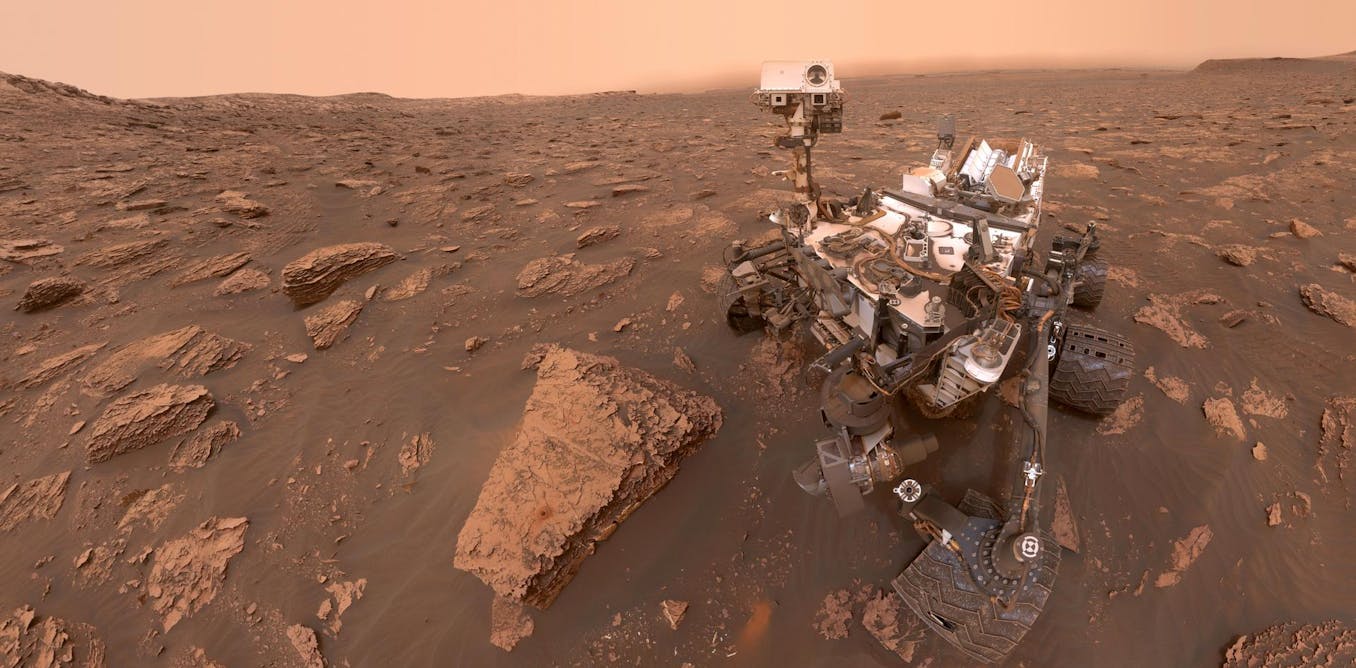

This has already started to happen. During the 2021 ransomware attack on JBS Foods, meat processing facilities halted operations despite animals, staff, and infrastructure being present. Although some Australian farmers were able to override the systems, there were widespread problems. More recently, disruptions affecting large distributors have shown how system failures can interrupt deliveries to shops even if goods are available.

Getting rid of humans

A significant issue is fewer people managing these issues, and staff training. Manual procedures are classified as costly and gradually abandoned. Staff are no longer trained for overrides they are never expected to perform. When failure occurs, the skills required to intervene may no longer exist.

This vulnerability is compounded by persistent workforce and skills shortages, which affect transport, warehousing and public health inspection. Even when digital systems recover, the human ability to restart flows may be limited.

The risk is not only that systems fail, but that when they do, disruption spreads quickly. This can be understood as a stress test rather than a prediction. Authorisation systems may freeze. Trucks are loaded, but release codes fail. Drivers wait. Food is present, but movement is not approved.

Based on previous incidents within days digital records and physical reality can begin to diverge. Inventory systems no longer match what is on shelves. After about 72 hours, manual intervention is required. Yet paper procedures have often been removed, and staff are not trained to use them.

These patterns are consistent with evidence from UK food system vulnerability analyses, which emphasise that resilience failures are often organisational rather than agricultural.

Food security is often framed as a question of supply. But there is also a question of authorisation. If a digital manifest is corrupted, shipments may not be released.

This matters in a country like the UK that relies heavily on imports and complex logistics. Resilience depends not only on trade flows, but on the governance of data and decision-making in food systems, research on food security suggests.

Who is in control?

AI can strengthen food security. Precision agriculture (using data to make decisions about when to plant or water, for instance) and early-warning systems have helped reduce losses and improve yields. The issue is not whether AI is used, but who is watching it, and who manages it.

Food systems need humans to be in the loop, with trained staff and regular drills on how to override systems if they go wrong. Algorithms used in food allocation and logistics must be transparent enough to be audited. Commercial secrecy cannot outweigh public safety. Communities and farmers must retain control over their data and knowledge.

This is not a risk for the future. It already explains why warehouses full of food can become inaccessible or ignored.

The question is not whether digital systems will fail, but whether we will build a system that can survive its failure.

The post “Replacing humans with machines is leaving truckloads of food stranded and unusable” by Mohammed F. Alzuhair, Candidate for a doctorate in business administration., Durham University was published on 02/10/2026 by theconversation.com