You might think a honey bee foraging in your garden and a browser window running ChatGPT have nothing in common. But recent scientific research has been seriously considering the possibility that either, or both, might be conscious.

There are many different ways of studying consciousness. One of the most common is to measure how an animal – or artificial intelligence (AI) – acts.

But two new papers on the possibility of consciousness in animals and AI suggest new theories for how to test this – one that strikes a middle ground between sensationalism and knee-jerk scepticism about whether humans are the only conscious beings on Earth.

A fierce debate

Questions around consciousness have long sparked fierce debate.

That’s in part because conscious beings might matter morally in a way that unconscious things don’t. Expanding the sphere of consciousness means expanding our ethical horizons. Even if we can’t be sure something is conscious, we might err on the side of caution by assuming it is – what philosopher Jonathan Birch calls the precautionary principle for sentience.

The recent trend has been one of expansion.

For example, in April 2024 a group of 40 scientists at a conference in New York proposed the New York Declaration on Animal Consciousness. Subsequently signed by over 500 scientists and philosophers, this declaration says consciousness is realistically possible in all vertebrates (including reptiles, amphibians and fishes) as well as many invertebrates, including cephalopods (octopus and squid), crustaceans (crabs and lobsters) and insects.

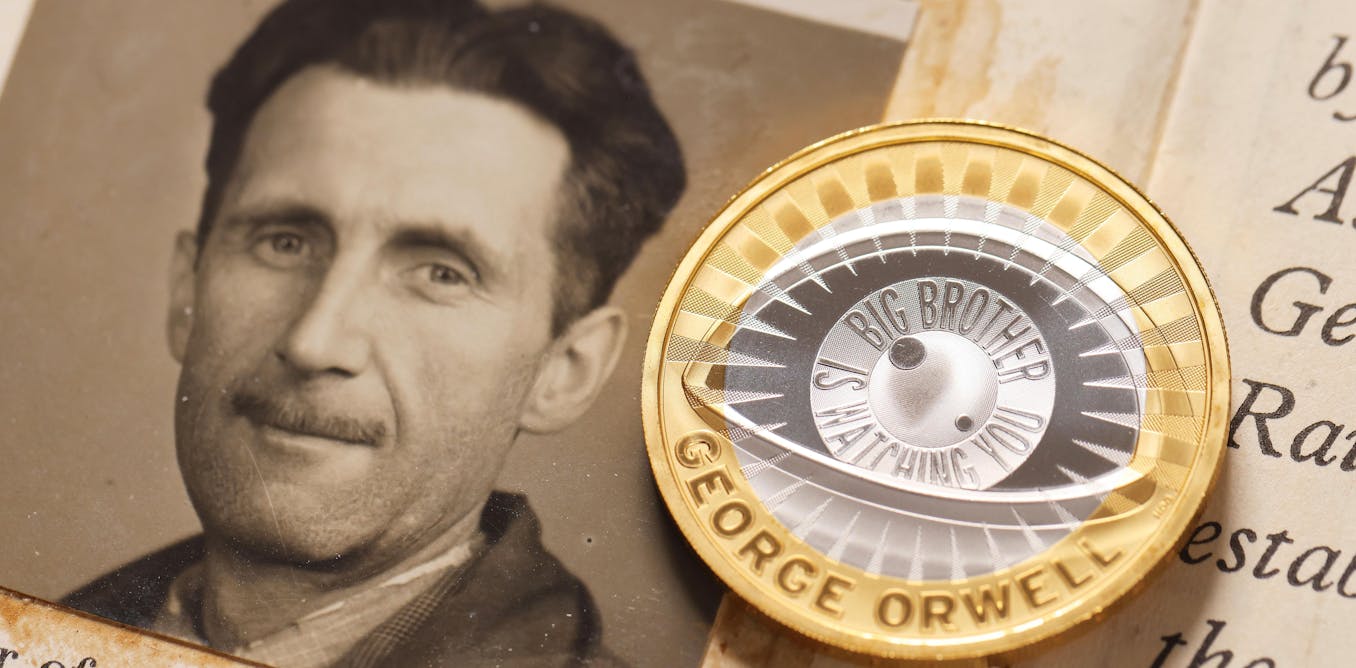

In parallel with this, the incredible rise of large language models, such as ChatGPT, has raised the serious possibility that machines may be conscious.

Five years ago, a seemingly ironclad test of whether something was conscious was to see if you could have a conversation with it. Philosopher Susan Schneider suggested if we had an AI that convincingly mused on the metaphysics of consciousness, it may well be conscious.

By those standards, today we would be surrounded by conscious machines. Many have gone so far as to apply the precautionary principle here too: the burgeoning field of AI welfare is devoted to figuring out if and when we must care about machines.

Yet all of these arguments depend, in large part, on surface-level behaviour. But that behaviour can be deceptive. What matters for consciousness is not what you do, but how you do it.

Looking at the machinery of AI

A new paper in Trends in Cognitive Sciences that one of us (Colin Klein) coauthored, drawing on previous work, looks to the machinery rather than the behaviour of AI.

It also draws on the cognitive science tradition to identify a plausible list of indicators of consciousness based on the structure of information processing. This means one can draw up a useful list of indicators of consciousness without having to agree on which of the current cognitive theories of consciousness is correct.

Some indicators (such as the need to resolve trade-offs between competing goals in contextually appropriate ways) are shared by many theories. Most other indicators (such as the presence of informational feedback) are only required by one theory but indicative in others.

Importantly, the useful indicators are all structural. They all have to do with how brains and computers process and combine information.

The verdict? No existing AI system (including ChatGPT) is conscious. The appearance of consciousness in large language models is not achieved in a way that is sufficiently similar to us to warrant attribution of conscious states.

Yet at the same time, there is no bar to AI systems – perhaps ones with a very different architecture to today’s systems – becoming conscious.

The lesson? It’s possible for AI to behave as if conscious without being conscious.

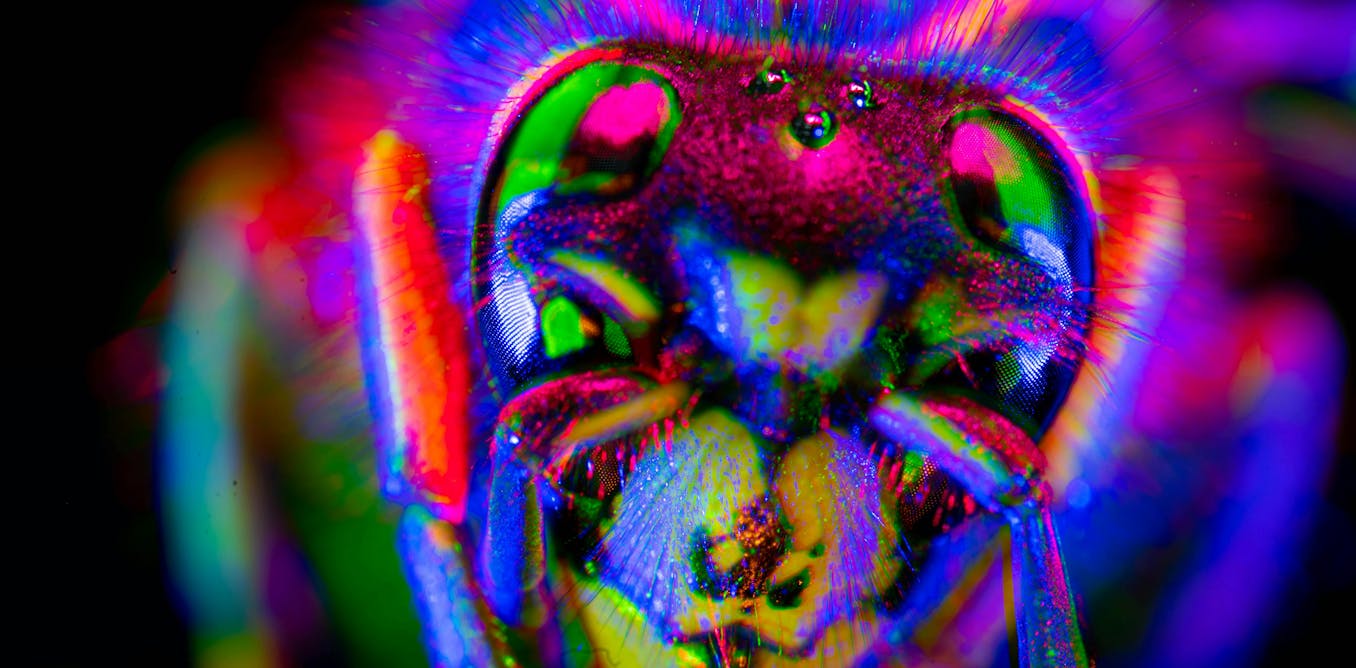

Measuring consciousness in insects

Biologists are also turning to mechanisms – how brains work – to recognise consciousness in non-human animals.

In a new paper in Philosophical Transactions B, we propose a neural model for minimal consciousness in insects. This is a model that abstracts away from anatomical detail to focus on the core computations done by simple brains.

Our key insight is to identify the kind of computation our brains perform that gives rise to experience.

This computation solves ancient problems from our evolutionary history that arise from having a mobile, complex body with many senses and conflicting needs.

Importantly, we don’t identify the computation itself – there is science yet to be done. But we show that if you could identify it, you’d have a level playing field to compare humans, invertebrates, and computers.

The same lesson

The problem of consciousness in animals and in computers appear to pull in different directions.

For animals, the question is often how to interpret whether ambiguous behaviour (like a crab tending its wounds) indicates consciousness.

For computers, we have to decide whether apparently unambiguous behaviour (a chatbot musing with you on the purpose of existence) is a true indicator of consciousness or mere roleplay.

Yet as the fields of neuroscience and AI progress, both are converging on the same lesson: when making judgement about whether something is consciousness, how it works is proving more informative than what it does.

The post “Are animals and AI conscious? We’ve devised new theories for how to test this” by Colin Klein, Professor, School of Philosophy, Australian National University was published on 11/18/2025 by theconversation.com