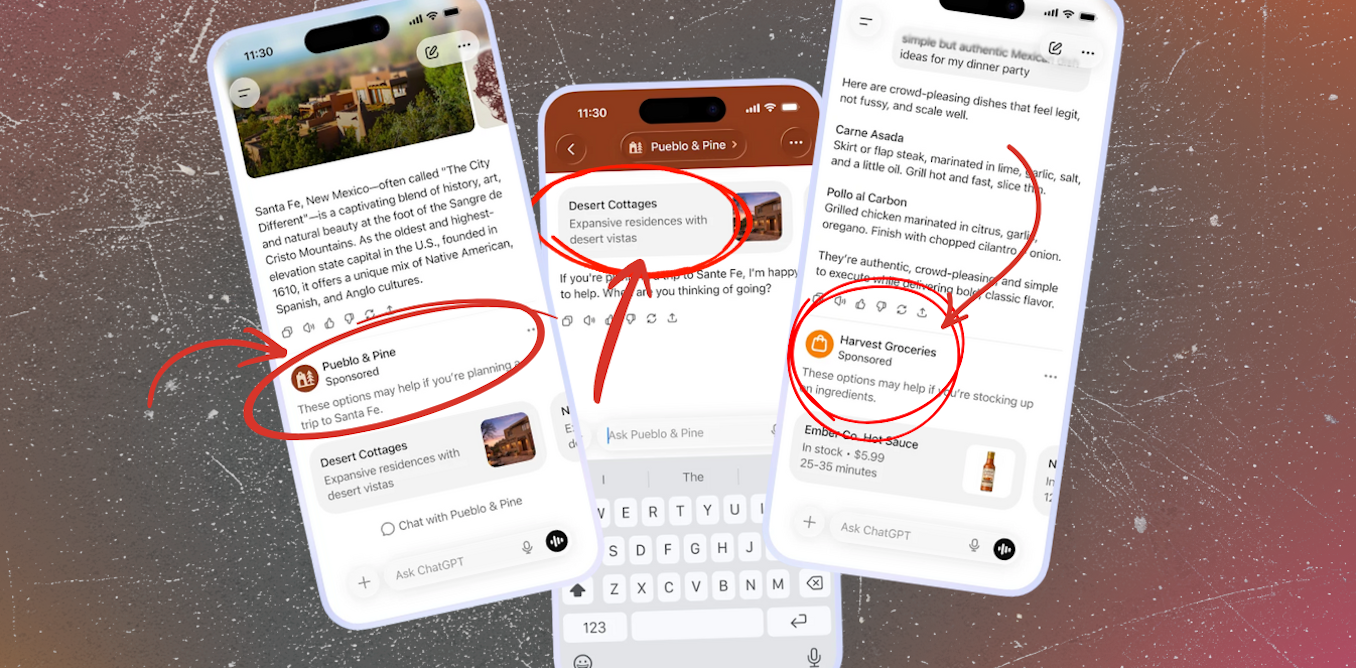

Many investors are asking themselves if we are living in an AI bubble; others have gone beyond that and are simply asking themselves, until when? Yet the bubble keeps growing, fuelled by that perilous sentiment of “fear of missing out”. History and recent experience show us that financial bubbles are often created by investor overenthusiasm with new “world-changing” technologies and when they burst, they reveal surreal fraud schemes that develop under the cover of the bubble.

A Ponzi scheme pays existing investors with money from new investors rather than actual profits, requiring continuous recruitment until it inevitably collapses. A characteristic of these schemes is that they are hard to detect before the bubble bursts, but amazingly simple to understand in retrospect.

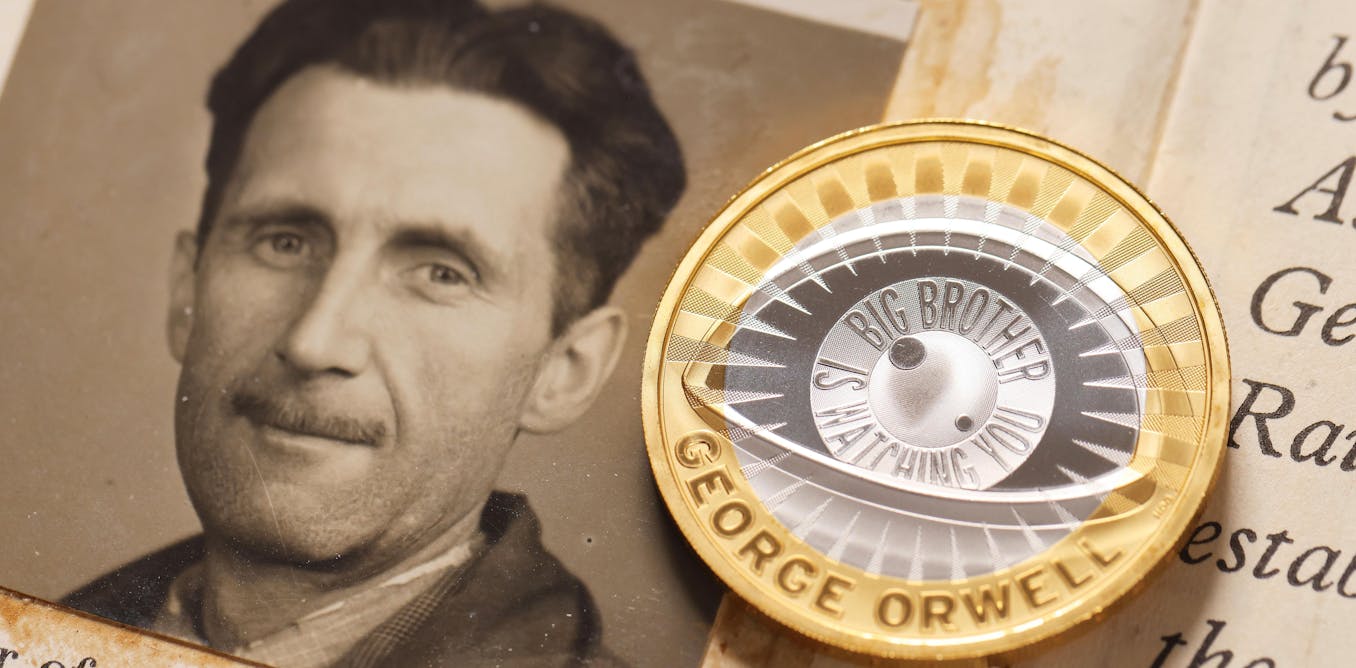

In this article we address the question What footprints do Ponzi schemes leave in technology-driven financial bubbles that might help us anticipate the next one to emerge under cover of the AI frenzy? We shall do this by comparing the “Railway King” George Hudson’s Ponzi of the 1840s with Bernie Madoff’s Ponzi enabled by the ICT (information and communications technology) and dotcom of the 1990s-2000s and sustained by the subsequent US housing bubble.

Macroeconomic climate, regulations and investor expectations

The railway mania in the UK started in 1829 as a result of investors’ expectations for the growth of this new technology and the lack of alternative investment vehicles caused by the government’s halting of bond issuance. The promise of railway technology created an influx of railway companies, illustrated by the registration of over fifty in just the first four months of 1845. Cost projections for railway development were understated by over 50 percent and revenue projections were estimated at between £2,000 and £3,000 per mile, despite actual revenues closer to £1,000 to £1,500 per mile. Accounting standards were rudimentary, creating opportunities for reporting discretion such as delaying expense recognition, and director accountability was the responsibility of shareholders rather than delegating it to external auditors or state representatives. Hudson, who was also a member of parliament, promoted the deregulation of the railway sector.

George Hudson’s Ponzi and Bernie Madoff’s Ponzi

Madoff’s reputation was built upon his success in the 1970s with computerization and technological innovation for trading. The dotcom bubble was fuelled by the rapid expansion of technology companies, with over 1,900 ICT companies listing in US exchanges between 1996 and 2000, propelled by which his BLMIS fund held $300 million in assets by the year 2000. Madoff’s scheme also aligned with the rapid growth of derivatives such as credit default swaps (CDS) and collateralized debt obligations (CDO), which grew 452 percent from 2001 to 2007. Significant market-wide volatility created a norm for outsized returns that hid the infeasibility of Madoff’s promised returns. These returns were considered moderate by investors, who failed to detect the implausibility of the long-term consistency of Madoff’s returns–this allowed the scheme to continue undetected. Madoff’s operations were facilitated by the fact that before the Dodd-Frank Act of 2010, hedge-fund SEC registration was voluntary; and by the re-prioritization of government security resources after 9/11, that led to a reduction of more than 25 percent in white-collar crime investigation cases opened between 2000 and 2003. The infeasibility of Madoff’s returns was overlooked by the SEC despite whistleblower reports instigating an SEC investigation–this reflects the SEC’s and other regulatory bodies’ lack of hedge-fund trading knowledge. It could also have been influenced by Madoff’s close relationship with the regulatory agencies, given his previous roles as Chairman of Nasdaq and an SEC market structure adviser.

At the time of the railway bubble-bust, Bank of England interest rates were at a near-century low, and similarly the FED’s lowering of interest rates in the 2000s reduced the cost of mortgages, which boosted demand and thus helped inflate housing prices. In both cases the markets were flush with cheap money and when everyone is making money (or thinking so), uncomfortable questions are not asked.

The perpetrators’ style and their downfall

Both Hudson and Madoff provided scarce information of their operations to fellow directors and shareholders. The former notoriously raised £2.5 million in funds without providing investment plans. Madoff employed and overcompensated under-skilled workers to deter operational questions and avoided hosting “capital introduction” meetings and roadshows to avoid answering questions from well-informed investment professionals–he instead found new investors through philanthropic relationships and network ties. There is evidence that shareholders were partially aware of Hudson’s corrupt business conduct but they did not initially object.

When their respective bubbles burst, in both cases their obscure business methods were unveiled and it was made evident that, in typical Ponzi-style, they were using fresh capital, and not investment profits, to pay dividends to investors. It was also revealed that they were using investor funds to finance their luxurious lifestyles. Hudson embezzled an estimated £750,000 (approximately £74 million in today’s money) from his railway companies, while Madoff’s fraud reached $65 billion in claimed losses, with actual investor losses of around $18 billion. Both ended in disgrace, Hudson fleeing to France and Madoff dying in goal.

On the trail of the fox

Beware when you see AI companies of ever-increasing market value, headed by charismatic and well-connected leaders–it is worrying that the heads of AI giants have such close relationships with the White House. In those cases, it is imperative to analyse the quality of communications with shareholders and prospective investors, particularly in terms of allocation of capital and disclosure of detailed cash flows. It is not enough to rely on audited financial statements; it must go much deeper into an investment strategy – obviously, this will require auditors to up their game considerably.

When investors are in a frenzy,

Around the corner waits a Ponzi.

Geneva Walman-Randall contributed to this article as a research assistant for her research on the conditions surrounding the Bernie Madoff and George Hudson Ponzi schemes. She completed this research as a visiting student at St. Catherine’s College, Oxford.

The post “Ponzi schemes and financial bubbles: lessons from history” by Paul David Richard Griffiths, Professor of Finance; (Banking, Fintech, Corporate Governance, Intangible Assets), EM Normandie was published on 12/17/2025 by theconversation.com