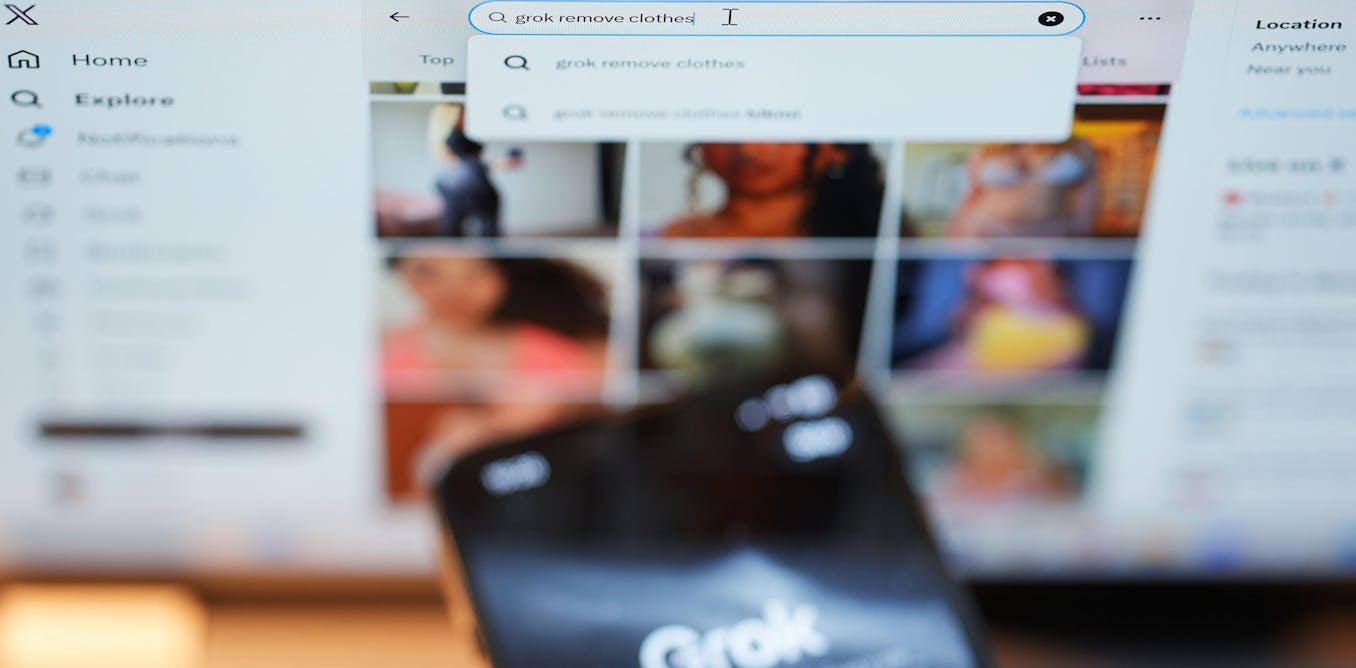

Talking monkeys vlogging from sacred sites, three-legged sharks wearing Nike sneakers, babies trapped in space… if you spend any time on social media these days you’re likely to come across such examples of what’s been dubbed “AI slop”.

These short videos are simultaneously flashy, generic and bizarre, characterised by uncanny visuals, robotic voiceovers and nonsensical narratives.

The rapid emergence of the generative AI video tools capable of conjuring such cinematic images from simple text prompts has been met with a mixture of awe, derision and concern.

Their outputs, often dazzling at first glance but riddled with odd features, occupy a strange place in our cultural landscape: too flawed to take seriously, but also too spectacular and pervasive to ignore.

Algorithmically optimised, these clips can rack up millions of views and generate significant profits for their creators.

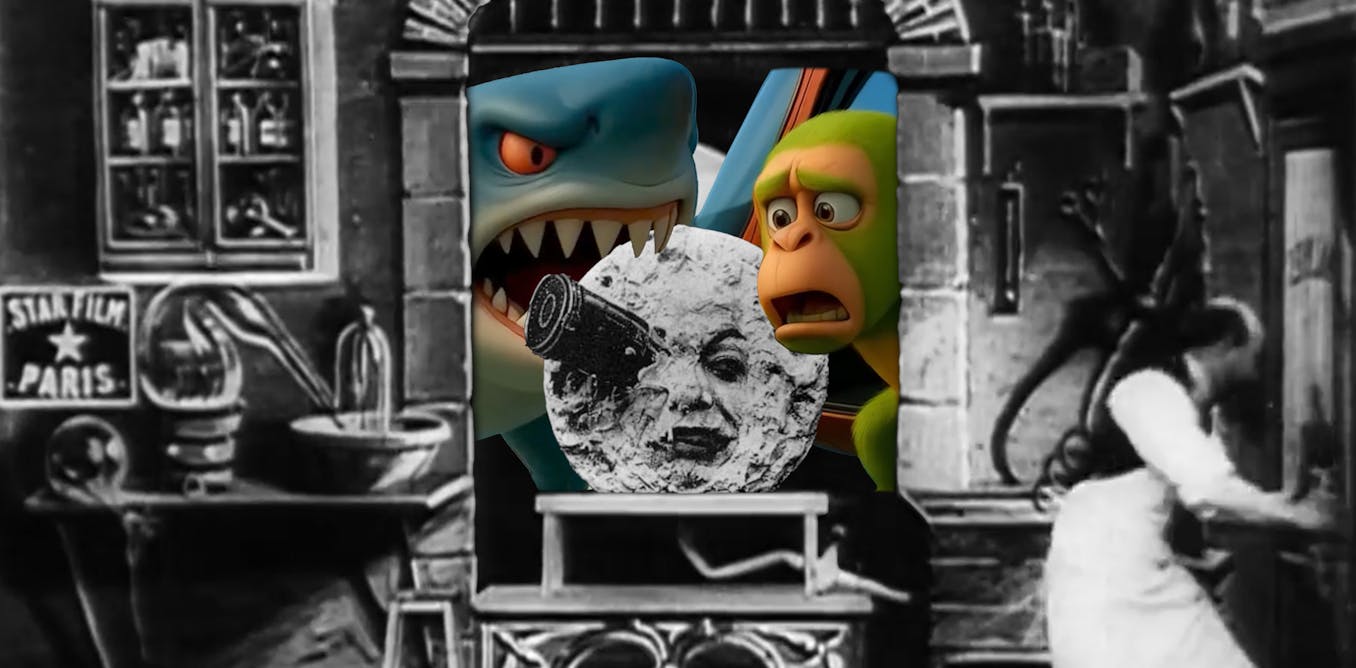

To understand this paradox, it’s useful to place generative AI video within a longer history of moving image culture – in particular, the “cinema of attractions”, a term coined by film scholar Tom Gunning to describe early film before the emergence of narrative-driven cinema.

Like AI slop, the cinema of attractions relied on spectacle, novelty and technological wonder to engage audiences. For example, AI creator FUNTASTIC YT’s videos of animated kittens embarking on weird misadventures evoke Thomas Edison’s 1894 Boxing Cats film.

Similarly, the “Italian brain rot” video memes characterised by casual violence and grotesque bodies echo the weird spectacle, cheap aesthetic thrills and questionable ethics associated with early films such as Edison’s disturbingly awful Electrocution of an Elephant (1903).

Awe and disappointment

In the first decade of its history, roughly between 1895 and 1908, cinema was less concerned with storytelling than with showing. The Lumière brothers’ Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat (1895) and Georges Méliès’ trick films were primarily designed to astonish their viewers.

Films flaunted their novelty, foregrounded special effects, and emphasised the act of looking itself. Gunning describes these films as “exhibitionist”, contrasting them with the “narrative integration” that would dominate cinema from the 1910s onward.

Generative AI video tools such as Veo 3, Kling AI and Runway’s Gen-2 exemplify a similar emphasis on spectacle and novelty. Much like early cinema, they function less as vehicles for coherent narrative than as attractions designed to show off what the technology can do.

The sense of awe they inspire stems from their ability to seamlessly blend fantasy and realism in ways unattainable by traditional cameras, and their capacity to generate customised viewing experiences.

Crucially, these tools also empower users to become creators, transforming audiences into active producers of visual content.

AI-generated videos and early films also share certain technological limitations. In AI slop, figures sprout extra limbs, mouths move unnaturally and objects flicker with instability. Viewers may marvel briefly at a “photorealistic” cat, but they soon notice the creature’s paws melt into the pavement or its body morphs unpredictably.

This tension between awe and disappointment echoes some of the reactions to early films, which were often poorly lit, jerky in motion and hampered by technical constraints.

The imperfections of early film and the glitches of AI videos both testify to the experimental nature of emerging media. These rough edges are part of their allure, inviting viewers to witness the boundaries of a new medium being tested in real time.

Awe, anxiety and dismissal

At the turn of the 20th century, film was dismissed by many cultural elites as a passing fad, a cheap amusement for the masses rather than a serious art form.

Intellectuals worried about cinema’s potential to corrupt morals or overstimulate children. It took decades for film to earn the same cultural legitimacy enjoyed by other art forms such as literature and painting.

Similarly, generative AI video is currently regarded with scepticism. Detractors label it “content pollution”, dismissing its lack of intentional artistry. There are also real concerns about AI’s impact on creative labour, the ethical implications of AI “training”, and the environmental costs associated with large-scale computation.

For now, AI-generated video is more often the butt of jokes than the subject of serious aesthetic discourse. And yet, just as early cinema eventually evolved into a sophisticated narrative and artistic medium, AI video may likewise progress beyond its current limitations.

Some creators are already experimenting with longer, narrative-based, AI-generated films. Recently, for example, OpenAI announced a partnership with international production companies to create Critterz, a feature film made almost entirely with AI.

AI-generated videos and early cinema undeniably emerged from radically different cultural, technological and historical contexts. But their similarities also illustrate the cyclical way in which new image-making technologies emerge, gain traction and provoke debate about artistic value.

A century ago, many dismissed the flickering images of trains and magic tricks as trivial amusements, while today we revere them as foundational works in the film history canon. Will the AI videos we mock now one day be seen as the Lumière reels of their era – crude, imperfect but bursting with the energy of a new way of seeing?

The post “what early cinema tells us about the appeal of ‘AI slop’” by Alfio Leotta, Associate Professor, School of Arts and Media, Te Herenga Waka — Victoria University of Wellington was published on 09/24/2025 by theconversation.com

-2.png)