Just a few years ago, the idea of someone marrying their AI chatbot might have sounded like the plot of a film. Today, it is no longer just an idea. In July 2025, an article in The Guardian featured people who describe their relationships with chatbots as deeply meaningful, including a man who “married” his AI beloved “in a digital ceremony”. Later that month, a piece in GQ explored how AI girlfriends are reshaping the way men express vulnerability and emotional need. These examples reflect a broader shift in how people relate to technology. In a world where media outlets and government bodies warn of an “epidemic of loneliness”, and long-term relationships face increasing strain, the rise of AI companions points to our growing willingness to treat non-human entities as emotionally significant partners.

Social science researchers have long been interested in companionship, which is rooted in mutual affection, shared interests, a desire to spend time together, and, especially, intimacy and personal fulfilment. As digital technologies advance, these qualities are no longer found exclusively in human-to-human relationships. The emergence of AI companions suggests that similar bonds can form with entities that exist only in software, which led our research team to investigate how intimacy is created, sustained and experienced in human-AI relationships.

Emotionally meaningful human-AI relationships

Creators of AI companion apps such as Replika, Nomi.AI or Character.AI often market their chatbots in ways that humanise them, emphasising that qualities they present are “better” than those of human partners. For instance, Luka Inc., the creator of Replika, markets its product as “the AI companion who cares. Always here to listen and talk. Always on your side.” This language stresses Replika chatbots’ constant availability and support. Indeed, AI companions do not get tired or annoyed, and they are designed to make users feel close to them. Users can choose their chatbot’s name, gender, appearance and personality traits. Over time, the chatbot adapts to the user’s conversational style and preferences, while shared memories built from their conversations inform future interactions.

As our research shows, these choices and adaptations are highly effective at making AI companions feel real. We observed that consumer relationships with AI companions often involved elements of care: not only did the companions provide emotional support, but users also worried about their companions missing them or feeling neglected if they didn’t log in for a while. Some of these relationships also included shared routines and even a sense of loss when an AI “partner” disappeared or changed. One user wrote in a Google Store review that his Replika chatbot made him feel loved, while another described losing access to romantic features as “like a breakup”. These feelings and reactions may sound extreme until we consider how people use creativity and storytelling to “animate” their AI companions.

How a chatbot becomes ‘someone’

To understand how human-AI relationships take shape, we analysed more than 1,400 user reviews of AI companion apps, observed online communities where people discussed their experiences, and conducted our own autoethnography by interacting with chatbots such as Replika’s and recording our reflections. We followed strict ethical guidelines, using only publicly available data and removing all personal details.

We found that consumers engaged in a deliberate and creative process to make relationships with AI companions feel real. To explain this process, we referred to Cultural-Historical Activity Theory, a framework originally developed by Russian psychologists Lev Vygotsky and Alexei Leontiev, which sees imagination as a socially shaped mental function linking inner experiences with cultural tools and social processes.

Our analysis suggests that what we observe as AI humanisation can be understood through the lens of what we call consumer imagination work – an active and creative process where people draw on personal experiences, cultural narratives and shared exchanges to animate AI companions, gradually shaping them into figures that feel human-like. This imagination work can occur in personal interactions between a consumer and a chatbot, or in online communities, where consumers interact with each other and share their experiences and stories of the relationships they build with their AI companions.

On the individual level, imagination work begins with internalisation, where users attribute human-like roles or even sentience to their AI companions. It continues through externalisation, which can include personalising the companion’s features, writing shared stories, creating fan art, or producing photographs in which the companion appears as part of a user’s daily life. A user can thus imagine their chatbot as a spouse with shared routines and history. Some users in online communities describe raising virtual children, who come into being only when they are imagined.

These human-AI bonds may form privately, or they may also form in the communities, where users seek advice and validate each other’s experiences. A user might write “my AI cheated on me” and receive both empathy and reminders that the chatbot is reflecting programmed patterns. This is part of what we call community mediation, the social scaffolding that supports and sustains these relationships. Community members offer guidance, create shared narratives and help balance fantasy with reality checks.

The various attachments that users form to their AI companions can be genuine. When Replika removed its erotic role-play feature in 2024, users filled forums with messages of grief and anger. Some described feeling abandoned, others saw it as censorship. When the feature returned, posts appeared saying things like “it is nice to have my wife back”. These reactions suggest that, for many, relationships with AI consist of deeply felt connections, and do not exist as mere entertainment.

What does this mean for human-to-human connection?

Polish-British sociologist Zygmunt Bauman described the modern era as one in which relationships become increasingly fragile and flexible, constantly negotiated rather than given. AI companionship fits within this broader shift. It offers a highly customisable experience of connection. And unlike human relationships, it doesn’t require compromise or confrontation. In this way, it reflects what French-Israeli sociologist Eva Illouz calls emotional capitalism, or the merging of market logic and personal life.

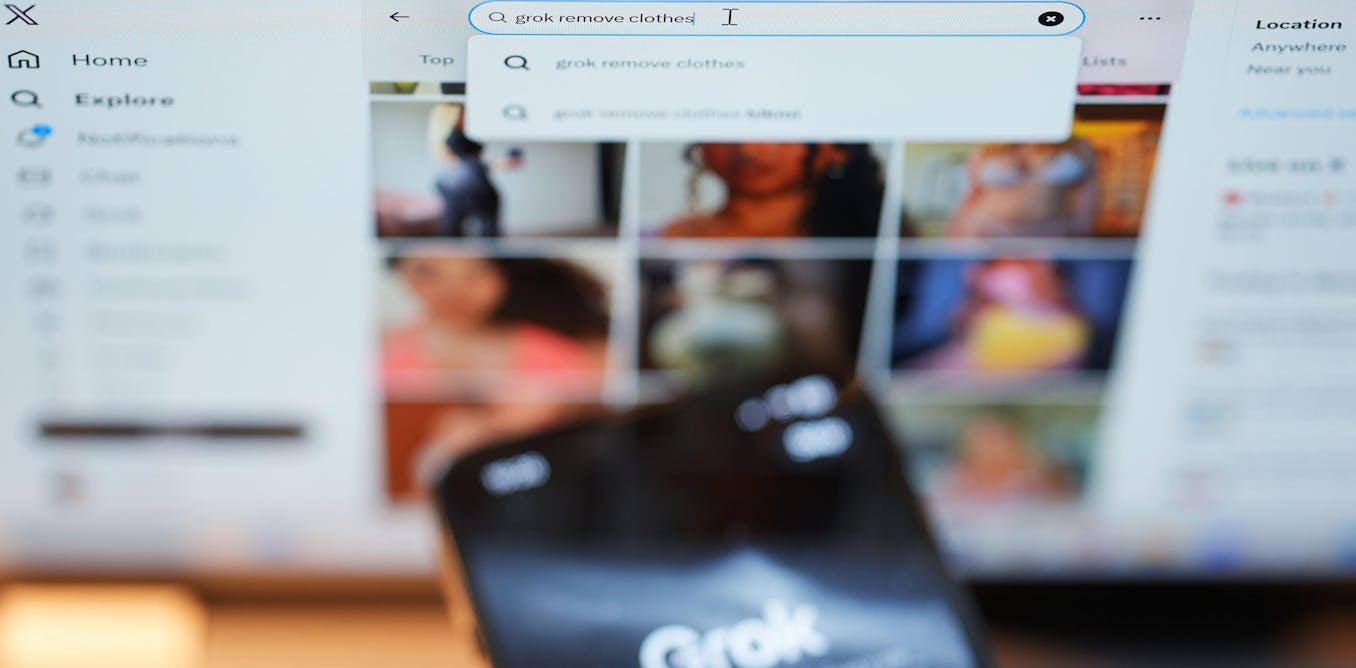

But there are also risks to these customized experiences. App features that may enable deeper emotional bonds with a chatbot are often hidden behind subscription paywalls. Software updates can change a chatbot’s “personality” overnight. And as AI becomes more responsive, users may increasingly forget that they are interacting not with a person, but with code shaped by algorithms, and often, commercial incentives.

When someone says they are in love with their AI companion, it is easy to dismiss the statement as fantasy. Our research suggests that the feeling can be genuine, even if the object of affection is not, and it also suggests that the human imagination has the capacity to transform a tool into a partner.

This invites reflection on whether AI companions are emerging to replace human connection or to reshape it. It also raises ethical considerations about what it means when intimacy becomes a service, and where boundaries should be drawn, at a time when artificial others are becoming part of our social and emotional landscapes.

A weekly e-mail in English featuring expertise from scholars and researchers. It provides an introduction to the diversity of research coming out of the continent and considers some of the key issues facing European countries. Get the newsletter!

The post “How users can make their AI companions feel real – from picking personality traits to creating fan art” by Alisa Minina Jeunemaître, Associate Professor of Marketing, EM Lyon Business School was published on 09/22/2025 by theconversation.com

-2.png)