Despite growing calls for diversity, equity and inclusion in science, a new study reveals how deep-rooted disparities continue to shape who gets to contribute to science.

We surveyed 908 environmental scientists from eight countries with varying levels of income and English proficiency. In our study, published in PLOS Biology today, we found that the gender, language and economic background of scientists significantly affect their ability to publish their work, especially in English.

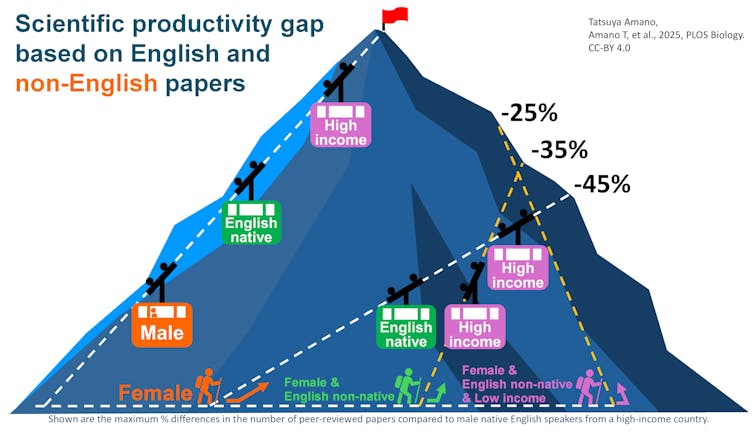

The results are striking. Women publish up to 45% fewer papers in English than men. Female non-native English speakers from lower-income countries publish up to 70% fewer papers in English, compared with a male native English speaker from a high-income country.

This gap doesn’t necessarily reflect individual productivity. Evidence shows it stems from systemic barriers that limit fair participation in science.

Tatsuya Amano, CC BY

The triple disadvantage

Scientific productivity is often measured by the researcher’s number of publications in English. But this metric overlooks the challenges faced by many researchers around the world.

Women already publish fewer articles, receive fewer citations and win fewer grants than men. They are also more likely to take career breaks for caregiving, and are less likely to be involved in collaboration compared with men.

As English is now the common language of science, non-native English speakers face additional hurdles. They spend more time writing papers, and are more likely to have their work rejected and returned for revision due to issues with English. They also often experience anxiety, imposter syndrome and lower satisfaction when conducting science.

Researchers from lower-income countries also struggle with limited funding, fewer opportunities for international collaboration, and travel restrictions.

When these three attributes intersect, the impact is overwhelming.

Taking English out of it

Importantly, when we looked at publications in English and in other languages combined, the productivity gap narrowed significantly.

Non-native English speakers and scientists from lower-income countries often publish more papers overall compared with their native English-speaking, high-income counterparts at the same career stage.

Tatsuya Amano, CC BY

Levelling the playing field

The findings have serious implications for how we should measure the performance of scientists. Metrics based solely on publications in English can misrepresent the true productivity of researchers who face language and economic barriers.

This is especially problematic in hiring, promotion and funding decisions. The number of publications in English often play a dominant role in these, even in countries where English is not widely spoken.

The Declaration on Research Assessment, a worldwide initiative, advocates that research assessment should focus on what is published rather than where it is published. Including publications in languages other than English in research assessment aligns with this policy.

In fact, publications in non-English languages can provide valuable knowledge, especially in fields such as biodiversity conservation. Recognising the importance of publications in various languages would also enrich global scientific understanding and allow us to tackle global challenges more effectively.

Institutions and funders should also consider disadvantages related to linguistic and economic backgrounds in research assessments. For example, the Australian Research Council has a policy that allows researchers to declare career interruptions due to factors such as caregiving or illness.

To level the playing field, this policy should also account for the systemic disadvantages experienced by non-native English speakers and scientists from lower-income countries.

Toward a more inclusive science

Recording the numbers on these disparities is just the first step. Making a real difference in dismantling these systemic barriers will likely require a fundamental shift in how we conduct science.

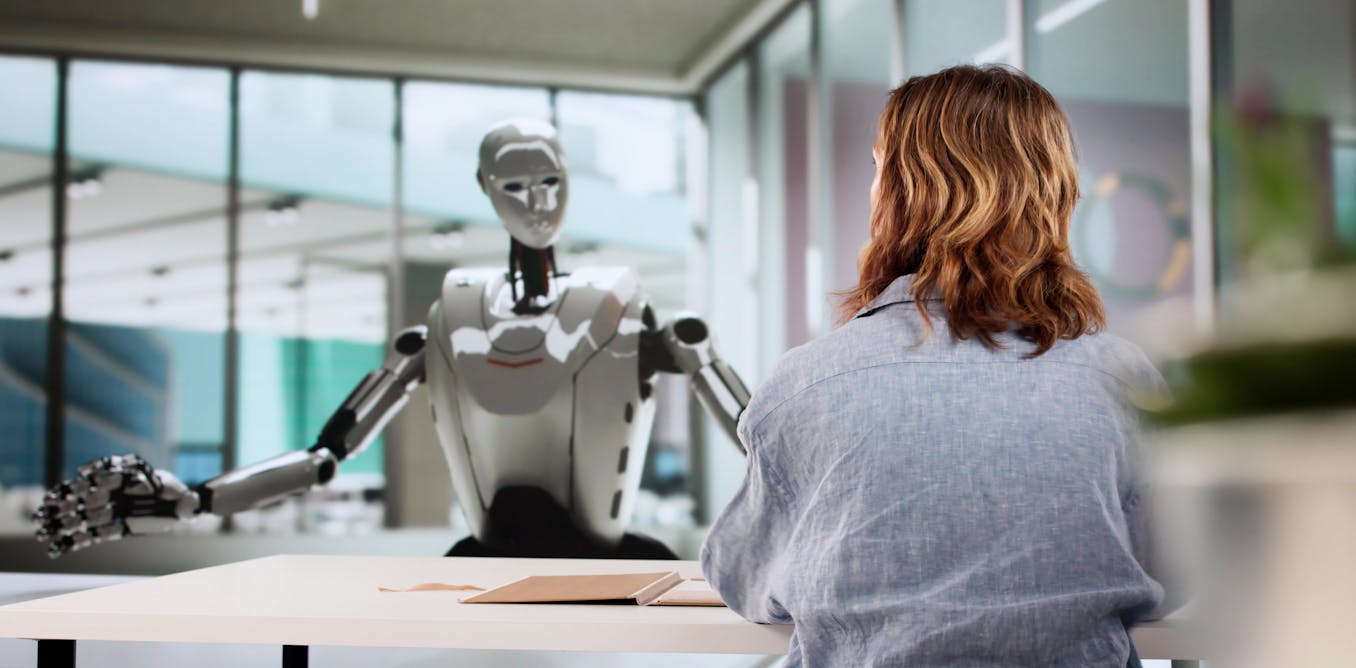

For example, artificial intelligence (AI) translation is rapidly improving and becoming more widely available. Would we still need to use English as the common language of science in, say, ten years’ time? We can start envisioning a future where everyone, regardless of linguistic background, can write papers in their own language and read any paper in their own language with the help of AI translation.

Amano et al. (2025) PLOS Biology, CC BY

If you find yourself struggling in science as a woman, a non-native English speaker, or someone from a lower-income country, remember it’s not just you. The challenges you face often come from bigger systemic barriers in science, not personal shortcomings.

Science is fun. Everyone, no matter their background, should have an equal chance to enjoy it. But as science becomes increasingly global, embracing diversity is not just a matter of equity. It’s essential for fostering innovation and addressing the complex challenges facing our world.

The post “Who gets to do science? A demand for English is hurting marginalised researchers” by Tatsuya Amano, Associate Professor, School of the Environment, The University of Queensland was published on 09/18/2025 by theconversation.com

-2.png)