People who aren’t legal experts are more willing to rely on legal advice provided by ChatGPT than by real lawyers – at least, when they don’t know which of the two provided the advice. That’s the key finding of our new research, which highlights some important concerns about the way the public increasingly relies on AI-generated content. We also found the public has at least some ability to identify whether the advice came from ChatGPT or a human lawyer.

AI tools like ChatGPT and other large language models (LLMs) are making their way into our everyday life. They promise to provide quick answers, generate ideas, diagnose medical symptoms, and even help with legal questions by providing concrete legal advice.

But LLMs are known to create so-called “hallucinations” – that is, outputs containing inaccurate or nonsensical content. This means there is a real risk associated with people relying on them too much, particularly in high-stakes domains such as law. LLMs tend to present advice confidently, making it difficult for people to distinguish good advice from decisively voiced bad advice.

We ran three experiments on a total of 288 people. In the first two experiments, participants were given legal advice and asked which they would be willing to act on. When people didn’t know if the advice had come from a lawyer or an AI, we found they were more willing to rely on the AI-generated advice. This means that if an LLM gives legal advice without disclosing its nature, people may take it as fact and prefer it to expert advice by lawyers – possibly without questioning its accuracy.

Even when participants were told which advice came from a lawyer and which was AI-generated, we found they were willing to follow ChatGPT just as much as the lawyer.

One reason LLMs may be favoured, as we found in our study, is that they use more complex language. On the other hand, real lawyers tended to use simpler language but use more words in their answers.

apatrimonio / shutterstock

The third experiment investigated whether participants could distinguish between LLM and lawyer-generated content when the source is not revealed to them. The good news is they can – but not by very much.

In our task, random guessing would have produced a score of 0.5, while perfect discrimination would have produced a score of 1.0. On average, participants scored 0.59, indicating performance that was slightly better than random guessing, but still relatively weak

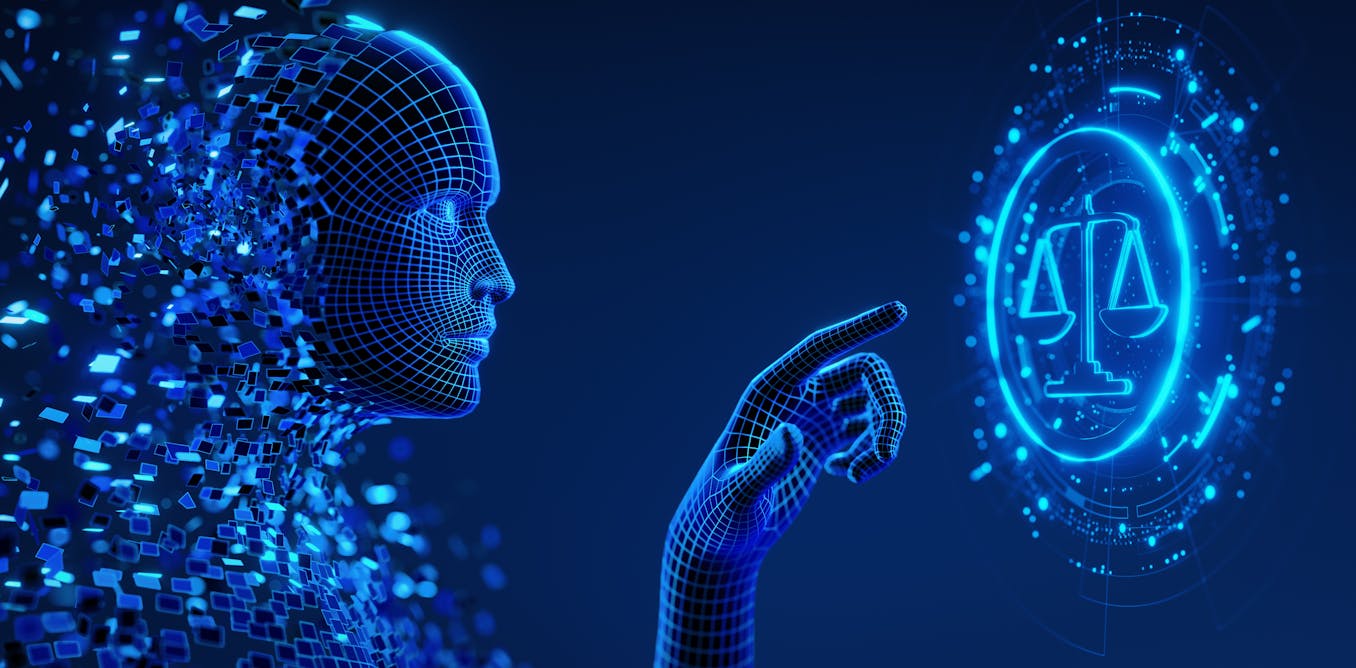

Regulation and AI literacy

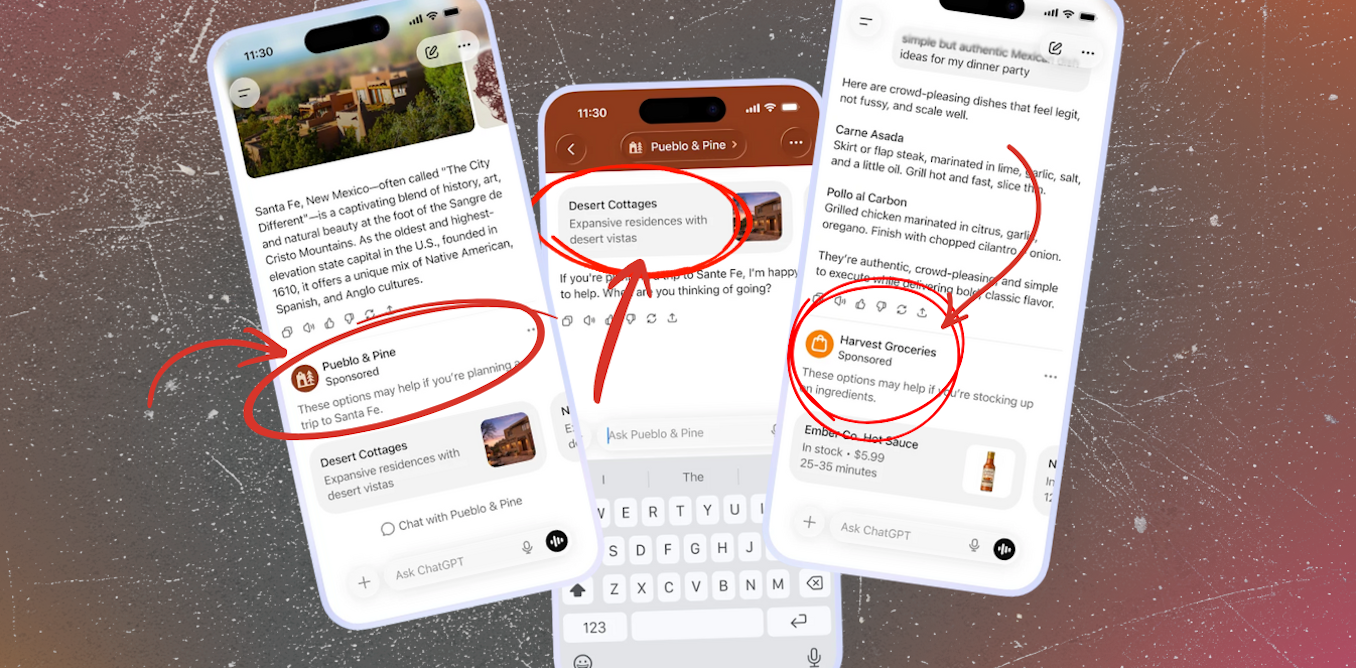

This is a crucial moment for research like ours, as AI-powered systems such as chatbots and LLMs are becoming increasingly integrated into everyday life. Alexa or Google Home can act as a home assistant, while AI-enabled systems can help with complex tasks such as online shopping, summarising legal texts, or generating medical records.

Yet this comes with significant risks of making potentially life altering decisions that are guided by hallucinated misinformation. In the legal case, AI-generated, hallucinated advice could cause unnecessary complications or even miscarriages of justice.

That’s why it has never been more important to properly regulate AI. Attempts so far include the EU AI Act, article 50.9 of which states that text-generating AIs should ensure their outputs are “marked in a machine-readable format and detectable as artificially generated or manipulated”.

But this is only part of the solution. We’ll also need to improve AI literacy so that the public is better able to critically assess content. When people are better able to recognise AI they’ll be able to make more informed decisions.

This means that we need to learn to question the source of advice, understand the capabilities and limitations of AI, and emphasise the use of critical thinking and common sense when interacting with AI-generated content. In practical terms, this means cross-checking important information with trusted sources and including human experts to prevent overreliance on AI-generated information.

In the case of legal advice, it may be fine to use AI for some initial questions: “What are my options here? What do I need to read up on? Are there any similar cases to mine, or what area of law is this?” But it’s important to verify the advice with a human lawyer long before ending up in court or acting upon anything generated by an LLM.

AI can be a valuable tool, but we must use it responsibly. By using a two-pronged approach which focuses on regulation and AI literacy, we can harness its benefits while minimising its risks.

Read more:

We asked ChatGPT for legal advice – here are five reasons why you shouldn’t

The post “People trust legal advice generated by ChatGPT more than a lawyer – new study” by Eike Schneiders, Assistant Professor, School of Electronics and Computer Science, University of Southampton was published on 04/28/2025 by theconversation.com